1. Early Life

Much of the available information about Boudica comes from Cornelius Tacitus, a Roman historian, who wrote that Boudica was born into an elite family in the ancient town of Camulodunum (now Colchester) around 30 AD.

She may have been named after Boudiga, the Celtic goddess of victory. Further, it is believed that Boudica would have been sent away to another aristocratic family to be trained in the history and customs of the tribe as well as learning how to use a spear, sword and shield, and ride a horse. However, Tacitus writes that Boudica was possessed of greater intelligence than often is found in women.

On this point, some historians assert that the ancient Celts were not literate and were educated in religion and weaponry. Tacitus may have been making an invidious comparison between Boudica and Celtic women in general. Roman men believed their women to be only suited for “elegance, adornment, and finery.” Apparently, he viewed Boudica as having more depth.

2. Early Career

It is believed that between 43 and 45 AD, Boudica married Prasutagus, King of the Iceni Tribe in East Anglia.

They had two daughters, Isolda and Siara. Prasutagus was a “client king” which meant he could keep his lands in exchange for supporting the Romans politically and paying them dues as a tribal leader.

Boudica served with Prasutagus for sixteen years. Men had the ultimate power in politics and the home, but she was allowed much freedom of activity and protection under the law.

Prasutagus died in 59 or 60 AD. Roman law provided that when client-rulers died their kingdoms became the property of the emperor. Prasutagus did not agree with that and left a will that left his kingdom jointly to his daughters, with Boudica serving as regent on their behalf, and the Roman emperor, Nero. Prasutagus’s wishes were unacceptable and Nero sent Catus Decianus, chief procurator, to claim Prasutagus’s kingdom for Rome.

Boudica protested Nero’s actions. Her behavior was foreign to the Romans because women had no say-so and were regarded as not fit to be a part of the political sphere. Decianus’s response was to tie her up and have her flogged for her brazenness. At the same time, some of his soldiers sexually abused her daughters.

3. Finest Works

Boudica was incensed at what happened to her and her daughters. She vowed revenge. It was also the last straw for the Iceni tribe.

For seventeen years, the Iceni had suffered at the hands of their supposed allies. They had been taxed unfairly, forced to serve in the foreign army, had their rulers emasculated, and deprived of their weapons. Boudica was a high-ranking individual among the Celtic leaders and what the Roman soldiers did was the ultimate insult to their royal family, their gods, and status of the whole tribe.

“We British are use to woman commanders in war. But I am not fighting for my kingdom and wealth now. I am fighting as an ordinary person for my lost freedom, my bruised body, and my outraged daughters.”

- Boudica

As the news spread of Boudica’s flogging and the princesses’s rape, the Iceni tribespeople left their fields and began to gather en masse near the royal residence. Tossing aside any tribal jealousies, the Iceni were joined by the Trinovantes, who had been bursting with unvented anger against the occupying army since 49 AD.

As Boudica watched the arrival of the Trinovantes and others arrive, she realized that the problem was no longer a personal matter, but that it was much bigger. The only solution was all-out war. However, she wondered about her ability to unite her people in revolt given their penchant for individual glory.

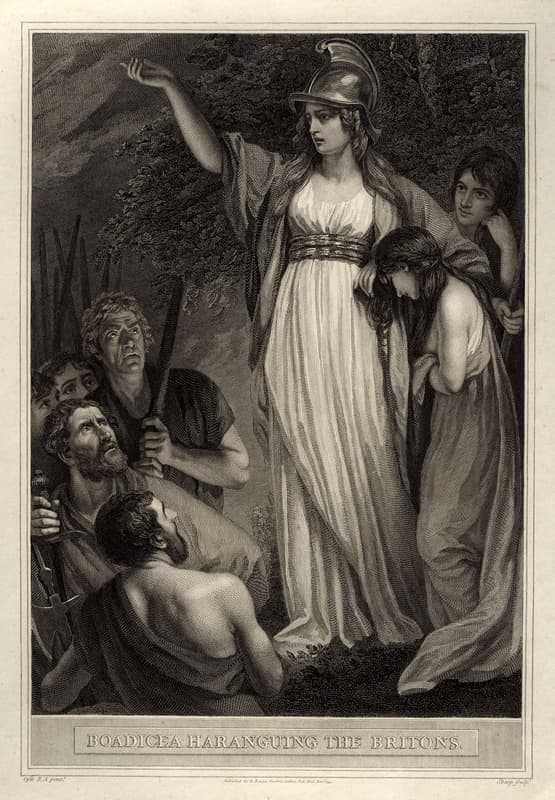

Boudica raised her hand to heaven and praised Andraste, an Icenic war goddess, and said, “I thank you, Andraste, and I call upon you as woman speaking to woman . . . I beg you for victory and preservation of liberty.”

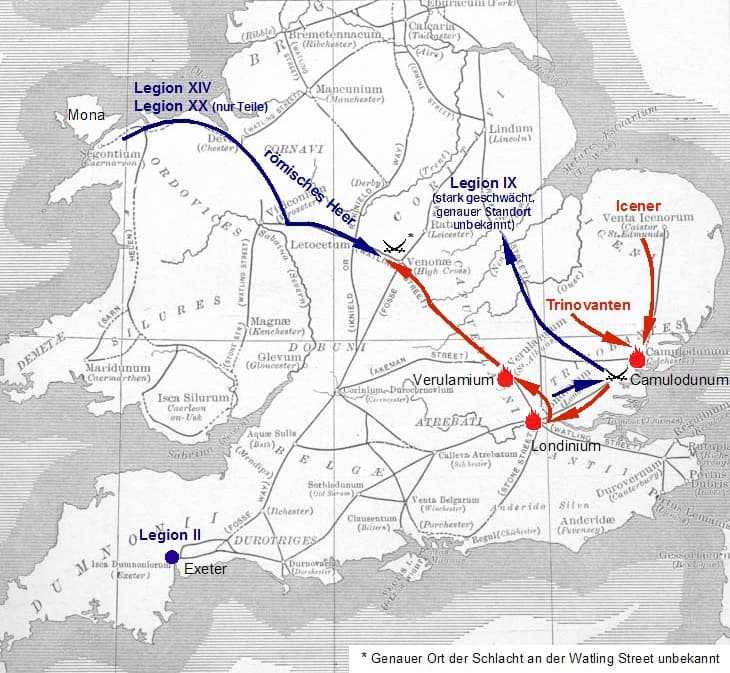

Boudica did not have a strategy of war. She was only intent on sacking any settlements that were home to their enemies and ultimately trying to free Britain from the tyranny of the Roman masters. Camulodunum was chosen as the first test of Boudica and her army’s fighting prowess. News of Boudica’s advancing army reached the Romans. Commanding the Ninth Legion was Petilius Cerealis who attempted to come to the aid of the Camulodunum’s citizens. However, Boudica’s forces ambushed him. Cerealis suffered heavy losses and had to retreat.

The men, women, and children in Camulodunum had sought refuge in the Temple of Claudius hoping to be safe until the Romans rescued them. Boudica’s forces crashed through the roof and everyone in the Temple was killed. The town was looted and the buildings burned.

The next target was Londinium, a trade center to the continent and inland to the rest of Britannia. Suetonius Paulinus heard of the pending attack and took a small group of men to defend the city. Realizing his small contingent of soldiers were no match for Boudica’s group, he chose not to fight and left. When Boudica and her men arrived, they found the city virtually empty. They killed its people, plundered, and burned the town.

Boudica’s next city on her list was St. Albans (Verulamin). It was not a Roman town per se, but a town of “Roman wannabees,” British collaborators who appeared to glory in everything Roman style.

The Trinovantes were anxious to attack St. Albans because they had an old score to settle with the Catuvellauni tribes who settled there. They had once been a neighboring tribe in Essex when they were defeated by King Cunobelin at the start of the new millennium. The Catuvellauni discarded their agricultural roots and built a Roman-British town, the third largest in the province.

The modus operandi of Boudica’s men was to “leave no prisoners.” Like the first two battle sites, they killed any inhabitants who had failed to escape, pillaged, and set the town on fire. The site of Boudica’s fourth and final battle is unknown. Some archaeologists have speculated that it might have been somewhere in the Chilterns because of the landscape. Boudica and her men faced Suetonius Paulinus, whose soldiers were precision trained fighters. Boudica had little knowledge of dealing with an organized enemy.

When the battle began, the Roman soldiers in concert let loose their javelins. Then, they used their daggers and double-edge swords. Boudica’s army fought bravely, but their efforts were fruitless. It is not clear what happened to Boudica when she realized that she had lost the battle for Britain. Tacitus wrote that she ended her life with poison.

4. The Legacy

Boudica’s achievements as an Iron Age warrior queen who almost drove the Romans out of Britain remained in the memories of the Romans and the Britons for over half a century.

She became a British folk hero whose name and deeds continue to be embedded in the popular consciousness with modern trope status in literature, art, and films. In 1864, Thomas Thorneycroft, a sculptor, began an equestrian statue of Boudica and her daughters. In 1902, seventeen years after his death, it was cast in bronze and erected at Westminster Bridge in London.

Boudica died in 60 AD. Her life has been transformed at various points in history, often in response to social injustice, in general, or to reflect the complexity of woman’s lives, e.g., women’s suffrage. Boudica was and continues to be the fighting spirit to whom women can relate.