1. Alfred the Great (AD 849-899)

Alfred was the youngest son of King Ethelwuf of Wessex and his first wife, Osburh. At four years of age, his father sent him to Rome hoping to win the favor of Pope Leo IV. A year later, Alfred returned and discovered that his mother had died.

Albert and his mother were close. After her death, his education was neglected. He didn’t learn to read until he was twelve. Alfred’s father died in AD 858 and his brothers, Ethelbald, Ethelberht, and Ethelred, reigned in succession.

In AD 867, Ethelred was king. Albert helped him fight several battles. After the battle at Mercia, Alfred was betrothed to and married Ealswith, a Mercian woman. In AD 871, Ethelred was killed at the battle at Basing and Alfred became king. He attacked the Vikings at Wilton and paid them a ransom for peace. Between AD 875 and AD 876, Guthrum, a Viking king, attacked by land and sea.

Alfred tried a ransom, exchange of hostages, and a sworn agreement, but Guthrum reneged. He attacked Alfred while he was celebrating Christmas holiday festivities. Alfred escaped and found refuge in Athelny. He led a successful charge at Edington and chased Guthrum to his camp at Chippenham. After two weeks, Guthrum surrendered. Alfred insisted that he accept the Christian God and be baptized. Guthrum accepted and Alfred named him Ethelstan.

Alfred had a few years of peace to implement some of his plans: restructure the army, build defensive walls in selective cities, and set up public schools. Alfred died in c. 899. He commissioned the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles which is a source of information for the history of the English language. In the sixth century, Alfred was given the epithet “The Greatest”.

2. Richard I (1157-1199)

Richard was the son of King Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine. He alternately lived in England and France with his mother.

At age fifteen, Richard was named Duke of Aquitaine and Count of Poitiers and helped rule these regions with his mother. He was highly cultured and learned to compose poetry and songs.

Richard’s father wanted to divide his kingdom among his sons. Henry the Young King, Richard’s older brother, was dissatisfied because he wanted to rule the land promised to him independently of his father. He convinced Richard to join him in a revolt against their father. He was aided by Louis VII, a French king. The revolt was unsuccessful. His father imprisoned his mother as he believed she was a co-conspirator.

Initially, Richard refused to accept his father’s peace offering. Later, he relented. His father gave him his own army and Richard protected his father’s kingdom.

Richard led a relentless two-month siege of Castillon-sur-Agen and was victorious. He acquired the name ‘the Lionheart’ for his brave leadership.

King Henry II died in 1189 and Richard became king. He went on the Third Crusade and took possession of Cyprus for England. Richard made a three-year peace treaty with Saladin, a Muslim leader, that allowed Christian pilgrims to travel to Jerusalem.

While in Cyprus, in 1191, Richard married Berengaria, daughter of King Sancho VI of Navarre. They traveled separately on the return trip to England. Richard was shipwrecked. As he traveled over a dangerous land route, he was captured, imprisoned, and a ransom placed on his head. His mother raised money for his freedom. He was recrowned in 1194 to nullify the shame of his imprisonment. Richard’s wife never saw him again until his death.

Richard died in 1199 in Chalus as a result of a blow from a crossbow. His heart was buried at Rouen in Norman, his entrails in Chalus, and the rest of his body at the feet of his father at Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou.

Richard is respected for his triumphs at the Third Crusade. He also introduced the heraldic design – Royal Arms of England (three lions), the national symbol of England.

3. Edward I (1239-1307)

Edward was the first son of Henry III and Eleanor of Provence. He training was in the knightly skills: hunting, horsemanship, sword, and lance. He grew to be over six feet tall and was nicknamed, ‘Long Shanks’.

At age fifteen, his father arranged a politically expedient marriage to thirteen-year-old Eleanor of Castile to affirm English sovereignty over Gascony.

Edward’s early adulthood was traumatic. His father had a penchant for war and in 1264, at the Battle of Lewes, he was taken hostage to ensure that his father would abide by the terms of peace. In 1265 Simon de Monfort, a rebel leader, initiated the Great Parliament so that representatives from the cities and burghs could meet and vote on financial issues, particularly taxation. Edward escaped and battled the rebels. Montfort was killed and in 1267 the rebellion ended.

In 1271, Edward landed in Acre during the Ninth Crusade. He made a truce with the Baibars. In 1272, while on the Crusade, Edward’s father died. Edward arrived in England in 1274 and was crowned king.

Edward wanted to rule England, Wales, and Scotland. The establishment of Parliament was now a permanent feature of English political life. A House of Commons had been created which was made up of wealthy ‘untitled’ members.

In 1277, Edward invaded Wales and defeated Welsh leader Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, killing him in 1282 at the Battle of Orewin Bridge.

In 1298, Edward fought the Battle of Falkirk. In 1304, Robert the Bruce led a Scottish rebellion. Edward died at Burgh on Sands in 1307. Written on his marble tomb are the words “Hammer of the Scots. Keep the Faith”.

4. Henry VIII (1491-1547)

Henry Tudor was the son of King Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. Among the subjects he studied were theology, music, and languages.

At the age of ten, Henry was given the title, Duke of Cornwall, New Prince of Wales, and Earl of Chester.

In 1509, Henry became king. He had initially rejected Catherine of Aragon, his deceased brother’s widow, but he agreed to marry her. They had a daughter, Mary, but after two decades, he was exasperated because Catherine didn’t give him a son.

He sought a divorce. The Pope denied it. In 1534, after receiving the backing of the Parliament and clergy, he declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England, initiating three statues: Act of Appeals, Act of Succession, and Act of Supremacy.

Over the next decade, Henry married five times: Anne Boleyn (1533), Jane Seymour, (1536), Anne of Cleves (1540), Catherine Howard (1540), and Catherine Parr (1543). He had a daughter, Elizabeth, with Boleyn and a son, Edward, with Seymour. Boleyn and Howard were accused of adultery and beheaded, and he annulled his marriage of a few days to Cleves.

He remained with Parr until his death in 1547. He was interned in a vault next to Jane Seymour in St. Georges Chapel at Windsor Castle. Her elder brother, Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford had been designated by Henry to be Lord Protector of the Realm as his son, Edward, was only nine years old.

5. Elizabeth I (1533-1603)

Elizabeth Tudor was the second child of King Henry VIII and his second wife, Anne Boleyn.

Elizabeth’s mother was beheaded when she was two. She was placed in the care of a governess, Catherine Ashley, who taught her French, Dutch, Italian, and Spanish.

After her father died, her half brother Edward VI became king. Before he died, he ignored the Act of Succession and Lady Jane Grey, the granddaughter of Henry VIII’s younger sister Mary, became Queen. Her reign was contested and lasted nine days. Later, Mary, Henry VIII’s daughter by Catherine of Aragon, became Queen. She reigned three years. She was Catholic and distrusted Elizabeth and had her imprisoned.

Mary died in 1558 and Elizabeth became Queen. She had been imprisoned for three months. She faced several problems. England was divided between the Protestants and the Catholics. England was also under threat of invasion from Spain, France, and Scotland.

In 1559, the first thing on Elizabeth’s agenda was the passage of the Act of Supremacy which re-established the Church of England and the Act of Uniformity which created a common prayer book. She also devised a compromise between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism with the Thirty-Nine Articles of 1563.

Elizabeth’s reign was termed the ‘Elizabethan Era’ and writers, such as William Shakespeare, flourished. However, in 1560, the country suffered from severe economic depression. To improve the situation and perhaps make a quick profit, Elizabeth made a decision that would have grave consequences. Slavery wasn’t legal in Britain, but it wasn’t ‘exactly’ illegal, which persuaded her to enter into an agreement with John Hawkyns, a slave trader.

Elizabeth tried to keep England at peace. The country’s navy had become the mightiest in the world led by Sir Francis Drake. When Spain attacked with its “Spanish Armada” in 1588, it was defeated. It was one of the greatest military victories in English history.

Elizabeth died in 1603. She never married and cultivated the image as the Virgin Queen who was wedded to her kingdom. She was interred in Westminster Abbey with her half-sister, Mary.

6. Charles II (1630-1685)

Charles was the eldest surviving child of Charles I, King of England, Scotland, and Ireland and Henrietta Maria of France. Charles was tutored in Latin, Greek, and math.

Charles’s early life was hectic. In 1640, when his father lost during the Battle of Edgehill, he had to flee to safety in France with his mother where she was living in exile. In 1648, his father was defeated at the Battle of Preston. He was captured and brought back to England and beheaded in 1649.

In 1649, the Scottish Parliament proclaimed Charles II king. Charles engaged in a conflict with Oliver Cromwell, leader of the New Army, and was defeated at the Battle of Worcester in 1651. He fled to mainland Europe and spent nine years exiled in France, the Dutch Republic, and the Spanish Netherlands.

Meanwhile, Cromwell became a dictator of England, Scotland, and Ireland. When he died in 1658, the monarchy was restored. Charles was invited to return. Charles assumed the throne in 1660.

The new parliament, called the Cavalier Parliament, passed several laws which prompted social change and lessened the Puritan momentum. These laws were called the Clarendon Code.

In 1662, Charles married Catherine of Braganza. Her dowry of Tangier and the Seven Islands of Bombay were a major influence in the development of the British Empire in India. Two ceremonies were held, a Catholic one in private and an Anglican service in public.

Charles was involved in numerous conflicts with the Dutch and the French, ultimately signing treaties with both, The Treaty of Breda with the Dutch and the Treaty of Dover with the French.

Charles didn’t have a good relationship with parliament during the 1670s because of his wars and religious policies. Charles dissolved the Cavalier Parliament in 1679. The new parliament was hostile and suspicious of Charles’s intentions. Charles’s wife had not had successful pregnancies and Charles had no heir. He planned to have his brother, James, Duke of York, as his heir. This was objectionable to the parliament because James was a Catholic. A bill termed the Exclusion Bill was introduced, but it was blocked by Charles. He retaliated by dissolving the parliament. During his last year, he ruled without a parliament.

In 1685, Charles died. He was buried in Westminster Abbey.

7. William III and Mary II

William was the only child of William II, Prince of Orange and Mary, Princess Royal, eldest daughter of King Charles I of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

William became Prince of Orange at birth, as his father had died eight days earlier. He received his education from several sources: Dutch governesses and a Calvinist preacher. At age nine, he entered the University of Leiden for his formal education.

Although he wasn’t officially enrolled, he spent seven years there. After his mother’s death in 1660 of smallpox, her will appointed William’s grandfather, King Charles I, as William’s guardian. As a peace condition of the Second Anglo-Dutch War, the king demanded the improvement of his grandson’s condition. Johan de Witt, Grand Pensionary took over William’s education and gave him weekly instructions in state matters.

Between 1660 and 1677, William found that becoming a Stadtholder was complicated. First, it was marred by the Act of Seclusion which forbade Holland from appointing a member of the House of Orange as Stadtholder. Next, in 1667, the Perpetual Edict denied the office of Stadtholder and Captain General.

In 1670, William was appointed Captain General of the Dutch States Army to deal with an impending Anglo-French attack. After refusing the position for a single campaign, he received a permanent position in 1672. After allying with Spain and Brandenburg, William was victorious and was appointed Stadtholder of several Netherland Provinces.

William wanted to improve his position with France and decided to marry Mary, his first cousin, who was the daughter of the Duke of York, later King James II.

8. Mary II (1662 -1694)

Mary was the daughter of James, Duke of York (later known as King James II of England) and Anne Hyde. Her governess, Lady Frances Villiers, supervised her education. The focus was on music, dance, drawing, French, and religious instruction.

In 1677, at age fifteen, as the result of political expediency, Mary married William III Prince of Orange. She immediately became pregnant, but she miscarried. Other medical problems hampered her ability to carry a child full-term and she and William never had children. Unlike her husband, who was regarded as aloof, she had a pleasing personality and the people loved her.

Mary’s father, King James II of England, was Catholic and he was unpopular with the Protestants. Influential political and religious leaders encouraged William to take over. In 1688, what became known as the Glorious Revolution, William invaded England. He landed at Brixham. The king was deposed and fled the country.

Mary was next in line to govern England, but she did not want to govern alone. In 1689, under the Declaration of Rights, the Parliament offered joint sovereignty. Later, the Bill of Rights was passed which marginalized sovereign powers. A month later, they accepted the Scottish crown.

Much of William’s early reign (1688-1697) was occupied with the Nine Years War. Mary had not had any training in history, geography, or law, but she ruled the country alone during his absence.

Mary died in 1694. Much of her influence can be seen in English pottery, landscape gardening, and interior decorating.

William did his best to contain France and keep it from imposing its will across Europe. He died in 1702. He was buried in Westminster Abbey with his wife. Since he had no heirs, his sister-in-law Anne, became Queen.

9. Queen Victoria (1819-1901)

Alexandrina Victoria was the daughter of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn and Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. She was called ‘little Drina’. She was taught her ABCs at age three.

At age eleven, she was tested to ascertain whether she was worthy to rule. She was drilled on Scripture, catechism, English, history, Latin, and arithmetic. She easily passed.

In 1837, Victoria’s grandfather, King George III died. Victoria became Queen. She was officially crowned in 1838.

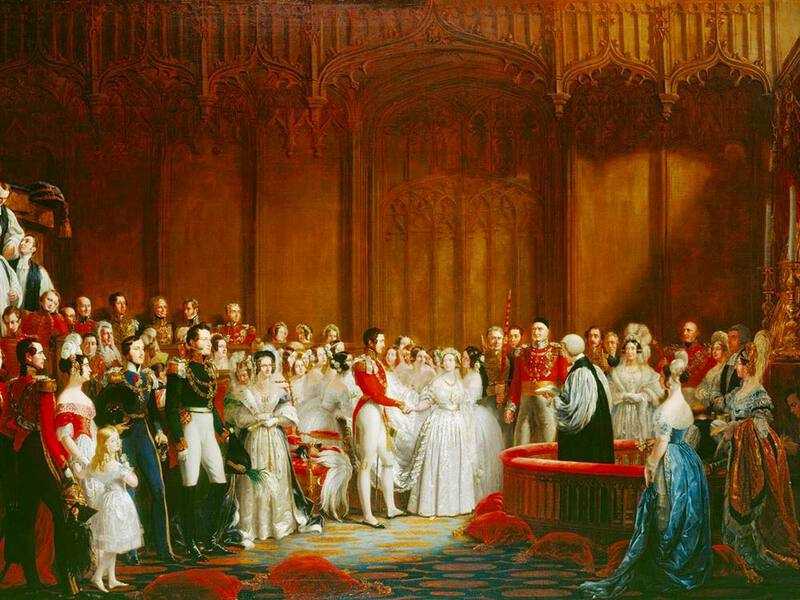

In 1840. Victoria married her first cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe Coburg and Gotha. She immediately became pregnant and over the course of seventeen years, she gave birth to nine children.

Early in her reign, Afghanistan, China, and a potato famine were among her problems, the latter. in 1846, killed millions of people in Ireland. The Crimean War and an Indian rebellion in British India followed.

Victoria died in 1901. She was interred beside Prince Albert, who had died in 1851, in the Royal Mausoleum, Frogmore at Windsor Great Park.

10. George VI (1895-1952)

King George VI was born Albert Frederick Arthur George Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. He was the second son of King George V and Victoria May, the Duchess of York.

Albert was nicknamed ‘Bertie’. He had knock knees and had to wear braces and, at age eight, he developed a stammer. He was naturally left-handed, but his tutors forced him to write with his right hand.

In 1909, Albert graduated from the Royal Naval Academy at Osborne and joined the Royal Navy. In 1916, as a midshipman, he served on the HMS Collingwood during the Battle of Jutland. Later, in 1919, he joined the Royal Air Force and received certification as a pilot.

In 1920, he was made the Duke of York. He had proposed marriage to Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon several times. She finally consented and they were married in 1923. They had two children, Elizabeth in 1926 and Margaret in 1930. Albert’s public duties required speechmaking, but his stammering had persisted. His wife sought assistance for him. Lionel Logue, an Australian speech therapist living in London, succeeded in helping Albert conquer his problem.

In 1936, Albert’s father died and his brother, Edward, succeeded him. Edward was in love with Wallis Simpson, a twice-divorced American. He wanted to marry her, but it was against the law. Rather than give her up, he abdicated the throne later that year, explaining to the nation:

“I have found it impossible to carry on the heavy burden of responsibility and to discharge the duties of king, as I would wish to do, without the help and support of the woman I love.”

Albert was crowned in 1937. He decided to take the name George VI to emphasize continuity with his father and restore confidence in the monarchy.

King George VI was faced with World War II. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had met with Adolph Hitler and signed the Munich Pact. In so doing, he believed Britain would be able to avoid war, but Hitler ignored the pact and attacked Poland. Britain declared war on Germany and in 1940 Winston Churchill replaced Chamberlain.

King George VI made visits to France, North America, and the United States. Franklin Roosevelt, President of the United States, had maintained an isolationist policy. After Japan entered the war and bombed Pearl Harbour, the United States entered the war. The King and Roosevelt developed a cohesive relationship.

King George VI had been saddled with myriad illnesses throughout his life and the war took a toll on his health. His penchant for smoking didn’t help and resulted in lung cancer and subsequent lung removal. In 1952, he died of coronary thrombosis. He was interred in King George VI Memorial Chapel inside St. George’s Chapel.

11. Queen Elizabeth II (1926-2022)

Queen Elizabeth II was born Elizabeth Alexandra Mary Windsor to Albert Frederick Arthur George, Duke of York (later King George VI) and Elizabeth Bowe-Lyon, Duchess of York. She identified herself as ‘Lilibet’ and the name stuck.

Elizabeth’s education was supervised by her mother and several governesses. History, language, literature, music, and French were among her studies.

During World War II, as the bombs fell, her parents remained in London as role models for the people. In 1940, Elizabeth made her first radio broadcast during the BBC’s Children’s Hour addressing children who had been evacuated from the cities.

In 1947, she married Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark. He converted to Anglicism and was given the title Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

Elizabeth traveled throughout the world on her father’s behalf. Her uncle, Edward, had abdicated the throne and her father had become king. She was heir presumptive and in 1952 while visiting Kenya for her father, he died. She became Queen and was crowned in 1953.

Since 1931 the British Empire had begun changing to a Commonwealth. South Africa had left the Commonwealth in 1961, but it rejoined in 1994. In 1980, it came under scrutiny for its practice of ‘apartheid’. Margaret Thatcher, Prime Minister during that time, didn’t endear herself to Elizabeth or the country when she vacillated on her decision to sanction South Africa for its practices.

In 1998, peace came to Northern Ireland after many years of turmoil. In 2012, Elizabeth shook hands with ex Irish Republican Army (IRA) leader, Martin McGuinness.

Elizabeth died on 8 September 2022, having spent 70 years on the throne. She is succeeded by her eldest son, King Charles III.

Britons champion the values of service, duty, steadfastness, charity, and stoicism. Elizabeth demonstrated them all throughout her reign. May she rest in peace.

People from all walks of life have celebrated Elizabeth's life and reign with inspiring words. They include:

"She was an inspiring presence to be around. I've been around her and she was fantastic. And she led the country through some of our greatest and darkest moments with grace, decency and a genuine caring warmth." Elton John

There was "nothing more noble than to devote your life to the service of others" Apple CEO Tim Cook

I was "struck by her warmth, the way she put people at ease, and how she brought her considerable humour and charm to moments of great pomp and circumstance." Barack Obama

"We have lost not just our monarch but the matriarch of our nation" Tony Blair

"Her dedication and devotion as Sovereign never wavered, through times of change and progress, through times of joy and celebration, and through times of sadness and loss." King Charles III

12. Conclusion

It should be noted that the above-mentioned men and women were not Gods, but just human beings with imperfections and conflicting thoughts and emotions, but, as the many statues and monuments seem to attest, their greatness stemmed from two qualities: their ability to use ‘good judgment’ and ‘kindness’ on enough occasions that helped preserve the crown, keep it stable, and enhance the overall advancement of the British people.