1. Early Life

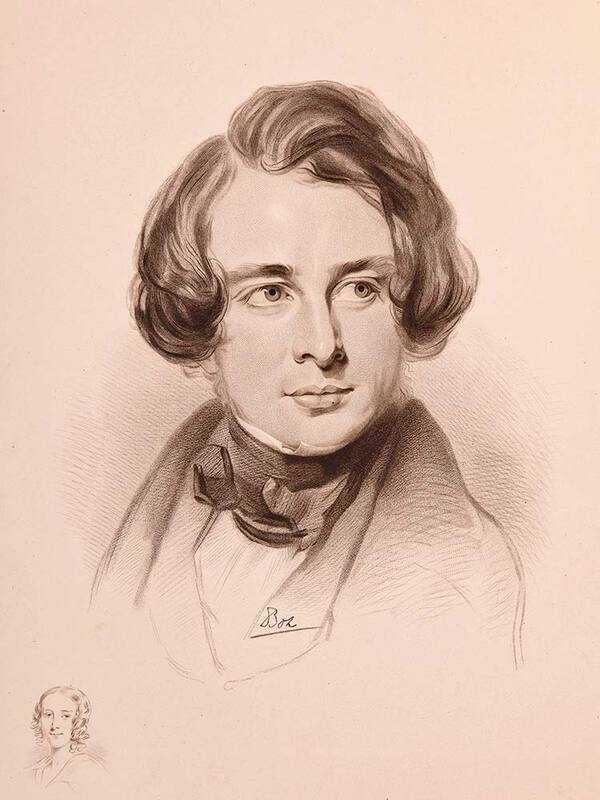

Charles John Huffam Dickens was born in February 1812 on a small island off the south coast of England called Landport.

He was the second of eight children born to John and Elizabeth Dickens. Charles’ first ten years were happy: his father was a clerk in the Navy and could pay for his son’s private education; and Dickens read widely and spent time outdoors.

Financial ruin

Financial disaster struck in 1822, when Dickens’ father, who was living beyond his means, was sent to the Marshalsea debtors’ prison. His wife and younger children went with him and Dickens boarded with a family friend in Camden, North London.

This brought an abrupt halt to Dickens’ education, and he was forced to work at Warren’s Blacking Warehouse—where he earned six shillings a week—to pay for his board and help his family.

Granny to the rescue!

The Dickens family got back on its feet when Charles’ great grandmother left them £450 in her will. With the family reunited, Dickens was sent to school in North London and then worked in a law firm inGray’s Inn. He spent his spare time learning shorthand and then used this newfound skill to assist a relative, Thomas Charlton, to report on legal proceedings.

Dickens’ next adventure was to try to break in to the world of acting. But that was short lived and Dickens became a political journalist. He spent his time reporting on events in parliament and covering election campaigns for the Morning Chronicle. His writing, and his sketches in particular, were sufficiently popular to be published as a collection, called Sketches by Boz in 1836.

A Parliamentary Sketch

Here's the first paragraph of one of Dickens' sketches, called 'A Parliamentary Sketch' (the rest of which can be read here):

Half-past four o’clock—and at five the mover of the Address will be ‘on his legs,’ as the newspapers announce sometimes by way of novelty, as if speakers were occasionally in the habit of standing on their heads. The members are pouring in, one after the other, in shoals. The few spectators who can obtain standing-room in the passages, scrutinise them as they pass, with the utmost interest, and the man who can identify a member occasionally, becomes a person of great importance. Every now and then you hear earnest whispers of ‘That’s Sir John Thomson.’ ‘Which? him with the gilt order round his neck?’ ‘No, no; that’s one of the messengers—that other with the yellow gloves, is Sir John Thomson.’ ‘Here’s Mr. Smith.’ ‘Lor!’ ‘Yes, how d’ye do, sir?—(He is our new member)—How do you do, sir?’ Mr. Smith stops: turns round with an air of enchanting urbanity (for the rumour of an intended dissolution has been very extensively circulated this morning); seizes both the hands of his gratified constituent, and, after greeting him with the most enthusiastic warmth, darts into the lobby with an extraordinary display of ardour in the public cause, leaving an immense impression in his favour on the mind of his ‘fellow-townsman.’

2. Later life

Dickens used the success of his sketches to get a deal from publishers Chapman and Hall.

His commission was to write The Pickwick Papers, for publication as a serial accompanied by picture plates. The story Dickens created, revolving around Samuel Pickwick’s travels through the English countryside, were so popular that the final instalment, published in 1836, sold 40,000 copies.

More books

Dickens’ next project was Oliver Twist, also written as a serial, and published in 1838. This was again popular and unusual for having a child protagonist. More books, usually published in serials, followed. Taking them in chronological order they were:

- Nicholas Nickleby in 1838-39;

- The Old Curiosity Shop in 1840-41 (legend has it that American fans met boats brining the latest serialisation at the docks);

- Martin Chuzzlewit in 1843-44;

- A Christmas Carol in 1843;

- David Copperfield in 1849-50;

- Bleak House in 1852-3;

- Hard Times in 1854;

- Little Dorrit in 1856;

- A Tale of Two Cities in 1859; and

- Great Expectations in 1861.

Other work

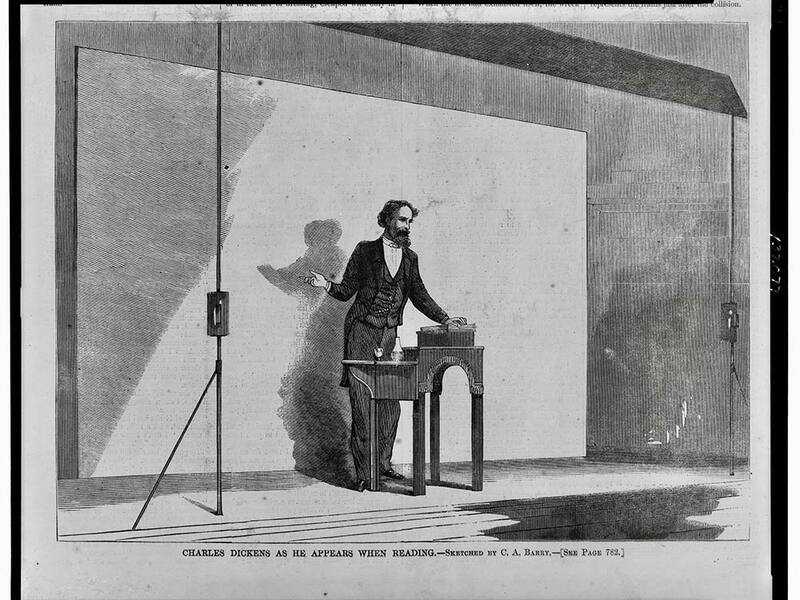

Aside from his novels, Dickens wrote non-fiction and for edited magazines such as All the Year Round and For the Theatre. He was a keen philanthropist (involved with Great Ormond Street Hospital, amongst others), and went on a large number of reading tours around Great Britain and Ireland and to America.

Personal life

Dickens married Catherine Thomson in 1837, had 10 children and separated in 1858. He left his wife and famously took up with a mistress, the actress Ellen Ternan, until his death.

Interesting fact ...

Rediscovered letters from Harvard University have shown that Dickens tried to have his wife, Catherine, committed to the Manor House Asylum in Chiswick in 1858, so that he could continue his affair with actress Ellen Ternan.

Dickens' personal life does not suggest he was a happy man. He publicly attacked his wife after they became estranged, complaining that she had put on weight and of her lack of energy. And he found his children a huge disappointment, once suggesting that it would be better if one of his sons were dead.

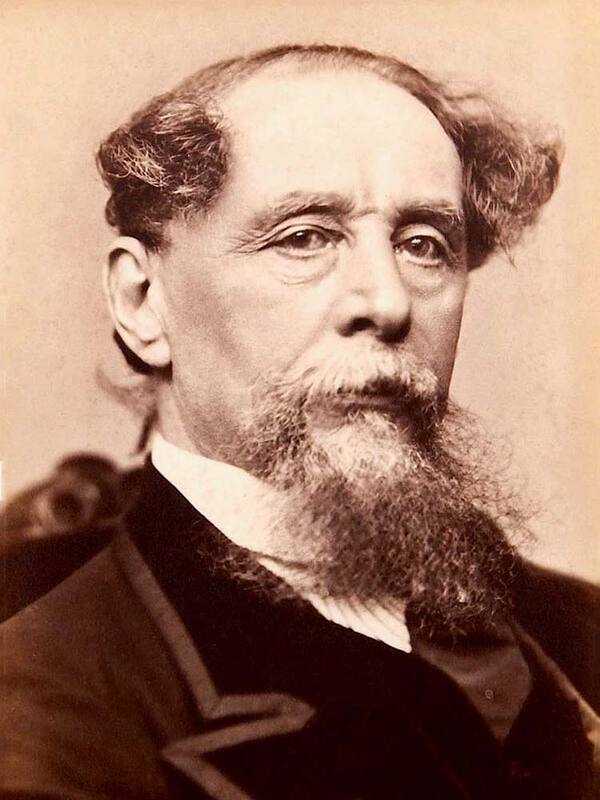

Later years

Dickens was involved in the Staplehurst rail crash in 1865, in which 10 people lost their lives. He was fortunate: the first class carriage, in which he was travelling, was the only one to remain on the tracks. Dickens tended to the injured and dying and was profoundly affected by the tragedy, with the result that his prolific pace of writing slowed substantially (though Dickens still carried out numerous speaking engagements).

Dickens died of a stroke in June 1870, five years to the day after the Staplehurst crash. He is buried in Westminster Abbey’s Poets Corner.

3. Novels

Many of Dickens’ novels had autobiographical elements to them.

Features of Dickens' writing

His unhappy childhood is used extensively in David Copperfield; his time as a legal clerk and court reporter in A Christmas Carol and Bleak House; and his family’s imprisonment in debtors’ prison in Little Dorrit, David Copperfield and Great Expectations.

There are a number of other remarkable features to Dickens’ writing. One is that his novels were written and published in weekly or monthly instalments, with Dickens’ readership expecting cliff-hangers at the end of each serial; yet he was able to produce a coherent whole at the end of the process.

Another is that Dickens pulled no punches in describing the shocking poverty and crime experienced by the least fortunate in society. By contrast, Dickens is often said to be a sentimentalist: A Christmas Carol, for instance, did much to revive the popularity of the Christmas season (which had fallen out of fashion in early Victorian times).

Classic Dickens quotes

You probably know quite a few Dickens quotes off by heart. Here are a few of the best:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair. (A Tale of Two Cities)

"Ask no questions, and you'll be told no lies" (Great Expectations)

"I loved her against reason, against promise, against peace, against hope, against happiness, against all discouragement that could be." (Great Expectations)

“Merry Christmas! What right have you to be merry? What reason have you to be merry? You’re poor enough. ... Bah ... Humbug. ... [E]very idiot who goes about with ‘Merry Christmas’ on his lips, should be boiled with his own pudding, and buried with a stake of holly through his heart. He should!”” (Scrooge in a Christmas Carol)

"A word in earnest is as good as a speech", "The universe makes rather an indifferent parent, I'm afraid", "All partings foreshadow the great final one", (Bleak House)

"The one great principle of the English law is, to make business for itself. There is no other principle distinctly, certainly, and consistently maintained through all its narrow turnings. Viewed by this light it becomes a coherent scheme, and not the monstrous maze the laity are apt to think it." (Bleak House)

"Please, sir, I want some more" (Oliver in Oliver Twist)

4. Impact

Dickens was the leading Victorian novelist, and probably the greatest writer since Shakespeare.

He popularised phrases such as ‘Bah, Humbug’, ‘scrooge’, the ‘Artful Dodger’ and ‘Merry Christmas’ and most will have heard of characters such as Tiny Tim, Oliver Twist, Fagin, Miss Havisham and Mr Micawber.

His books have never gone out of print, have been translated into all major languages, and have been adapted to over 200 television productions and films.

Statistics for the overall number of books sold by Dickens are unavaiable, though the Economist reported on the 200th anniversary of his birth that during Dickens' life his top-selling work was Bleak House (which sold over 750,000 copies).

The Times got it right when, on his death, it wrote: "The loss of such a man is an event which makes ordinary expressions of regret seem cold and conventional".