1. Early life

Francis Drake was born between 1540 and 1544 near Tavistock, Devon.

He was the son of Edmund Drake, a Protestant farmer, and his wife Mary Mylwaye. He was the oldest of their 12 sons.

The Drakes were related to the Hawkins family of Plymouth, who were shipowners, merchants and privateers.

When Drake was about 18, he enlisted in the Hawkins family fleet, which prowled for shipping to seize off the French coast.

2. Drake at Sea

The Hawkins family also had an increasing interest in African trade. Drake’s cousin John Hawkins, a naval commander, was the first Englishman to trade in slaves.

In 1563, Drake and John Hawkins sailed to Africa on one of the Hawkins’ fleet of ships, in order to join the slave trade. They attacked Portuguese towns and ships on the coast of West Africa, then sailed to the Americas and sold the captured cargoes of slaves to Spanish plantations.

The cousins made three expeditions on this fleet, but the third expedition ended in the ill-fated 1568 incident at San Juan de Ulúa (Veracruz, Mexico). Whilst negotiating to resupply and repair at the port in Mexico, the English fleet was attacked by Spanish warships, with all but two of the English ships lost.

Drake and Hawkins escaped, returning to England, but many of Drake and Hawkin’s crewmates were killed in the attack. Drake’s experience at San Juan de Ulúa began what would be a lifelong hatred for Spain and its ruler, King Philip II.

Although the expedition was a financial failure, it brought Drake to the attention of Queen Elizabeth I, who had herself invested in the slave-trading venture. In the years that followed, he made two expeditions in small vessels to the West Indies, in order “to gain such intelligence as might further him to get some amend for his loss”.

Americas

Having married Mary Newman of Plymouth in 1569 he was back at sea the following year for the Spanish Main with a small crew aboard the 25-ton Susan.

He hoped to learn how the Spaniards arranged for shipping Peruvian treasure home, and he felt that the ports of Panama City and Nombre de Dios on the Isthmus of Panama were the key.

His 1570 voyage was largely one of reconnaissance during which he made friends with the Cimaroons, who were escaped slaves dwelling out of Spanish reach on the Isthmus and stood ready to help him.

During a 1571 expedition he captured Nombre de Dios with Cimaroon help but lost it immediately when he was wounded in the attack. The mission failed but Drake and his men managed to make up for their loss by intercepting a Spanish gold train near Nombre de Dios. He returned to England with the bounty both rich and famous.

Circumnavigation of the globe

In 1577, Queen Elizabeth commissioned Drake to lead an expedition around South America.

Drake's main instructions were to sail through the Strait of Magellan (a narrow waterway in the southern tip of Argentina) and probe the shores of Terra Australis Incognita. Drake received five ships, the largest being the Pelican (later named the Golden Hind), and a crew of about 160.

The voyage was plagued by conflict between Drake and the two other men tasked with sharing command. When they arrived off the coast of Argentina, Drake had one of the men – Thomas Doughty – arrested, tried and beheaded for allegedly plotting a mutiny.

Of the five-ship fleet, two ships were lost in a storm; the other commander, John Wynter, turned one back to England; and another disappeared. Drake’s 100-tonne flagship, the Pelican was the only vessel to reach the Pacific, in October 1578.

Drake then travelled up the west coast of South America, plundering Spanish ports. He continued north, hoping to find a route across to the Atlantic, and sailed further up the west coast of America than any European.

Unable to find a passage, he turned south and then in July 1579, west across the Pacific. His travels took him to the Moluccas, Celebes, Java and then round the Cape of Good Hope. He arrived back in England in September 1580 with a rich cargo of spices and Spanish treasure and the distinction of being the first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe.

Despite Spanish protests about Drake’s

“piracy while in their imperial waters”

Queen Elizabeth herself went aboard the Golden Hind, which was lying at Deptford in the Thames estuary, and personally knighted him.

In 1581, Drake was made mayor of Plymouth. He organised a water supply for Plymouth that served the city for 300 years. Drake’s first wife, Mary Newman, died in 1583, and in 1585 he married again. His second wife, Elizabeth Sydenham, was an heiress and the daughter of a local Devonshire magnate, Sir George Sydenham.

Drake purchased a country house - Buckland Abbey (now a national museum said to be haunted by Drake’s spirit), a few miles from Plymouth.

The Spanish Armada

In 1585, hostilities between England and Spain heated up again. Drake was given carte blanche by the queen to “impeach the provisions of Spain”.

He sailed to the West Indies and the coast of Florida and plundered Spanish ports there, taking Santiago in the Cape Verde Islands, Cartagena in Colombia, St. Augustine in Florida and San Domingo. On the return voyage, he picked up a failed English military colony on Roanoke Island off the Carolinas.

Drake then led an even bigger fleet (30 ships) into the Spanish port of Cádiz and destroyed a large number of vessels being readied for the Spanish Armada.

This action, which Drake laughingly referred to as

“singeing the king of Spain’s beard”

helped to delay the invasion fleet for a further year.

In 1588, Drake served as second-in-command to Admiral Charles Howard in the English victory over the Spanish Armada.

3. His later years

After a failed 1589 expedition to Portugal, Drake returned home to England for several years.

Queen Elizabeth eventually enlisted him for one more voyage, against Spanish possessions in the West Indies in early 1596.

Once again he teamed up with his cousin, John Hawkins, in what was to be their last mission. The Spanish were prepared for Drake this time, and the expedition failed.

Drake came down with fever and dysentery, and died on 28 January 1596 off the coast of Portobelo, Panama. Hawkins too died around the same time, and their bodies were buried at sea.

4. Drake’s legacy

Sir Francis Drake most certainly left a legacy - revered sailor, slave trader, privateer or pirate, politician and the first Englishman to circumnavigate the world.

His accomplishments cemented English dominance at sea.

The Spanish Armada never fully recovered from Drake’s victories. This loss weakened their grip in the New World, and allowed the British to establish themselves as a great empire.

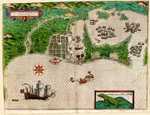

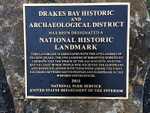

In addition to his legendary exploits, he also claimed part of the west coast of North America for England. Drakes Bay near San Francisco bears the name of the great explorer who helped claim the lands for the English.

Drake's Memorial

In 1979, a memorial to the Elizabethan sailor and explorer was unveiled in the south cloister of Westminster Abbey.

The oval memorial, known as the Navigators' Memorial, also commemorates Captain James Cook and Sir Francis Chichester, who all sailed around the world in different eras. The mosaic of coloured marbles shows a map of the world on which are the three ships of the navigators.

The Mojito

Drake is less commonly remembered as the man behind the mojito cocktail. Infamously known by his enemy as ”El Draque”, it is said that Drake’s fellow privateer and cousin Richard Drake invented a drink which he named El Draque.

El Draque comprised of ingredients found on their voyages such as sugar from the plantations, a variety of mint which grew naturally in and around the sugar plantations, key limes, and a cane spirit which was most likely cachaça rather than rum.

Cuban rum historian Fernando Campoamor discovered evidence that Drake was given this concoction as a remedy to settle his stomach when affected by the tropical environment along his voyages.

Centuries after Drakes death, a concoction known as “Drakes” or “Draquecitos” (Little Drakes) were still consumed by Caribbean settlers as a refreshing drink.