1. Early Life

Aneurin Bevan was born on November 15, 1897 in Tredegar, South Wales. He was the sixth of ten children born to David Bevan, a coal miner, and Phoebe, the daughter of a colliery blacksmith.

Of the ten children, only six survived to adulthood. Bevan began his education at Sirhowy Elementary School. He had an intense stammer. William Orchard, his headmaster, was a ruthless task master who inflicted verbal and physical abuse on his students. On one occasion Bevan fought back after being physically assaulted by Orchard. Orchard retaliated by keeping Bevan in a lower class for a year. This did not deter Bevan. He joined the Sirhowy Bridge lending library. Later, he secured a job as a butcher’s boy. He used his earnings to buy boys’ books. Jack London, an American socialist, was one of his favorite writers.

Bevan’s lifelong love of reading was inspired by his father. Over the years Bevan would come to believe that “what the self-educated learn, they hold and what they hold is an illumination of their own experience.”

Shortly before his fourteenth birthday, Bevan left Sirhowy. He did not try for secondary school. He sought work in the mines. He worked on the Ty-tryst Colliery. While working there, he also took advantage of the Tredegar Workmen’s Institute Library.

Bevan worked at several different pits and he was very vocal. In 1916, at the age of nineteen, Bevan was appointed head of his Miner’s Lodge. He believed in collective strength and worked to create the Tredegar Combine Lodge, which amalgamated twelve pits around the town.

During World War I unmarried men were conscripted to serve. Bevan was served with papers, but he was rejected when he produced a medical certificate confirming that he had nystagmus, a disease of the eyes. In 1919, the Tredegar’s Labour Party was formed and Bevan joined. He ran and lost in the West Ward Council elections of April 1919. Later, he sat for an examination for the South Wales Miners’ Federation (SWMF) scholarships and passed. He was sent to Central Labour College in Earl’s Court in West London. For two years, he studied economics, politics, and history.

2. Early Career

In 1922, Bevan was elected to the Tredegar Urban District Council. Over the next six years he would show himself not only to be a fiery debater, but also to have a strong practical streak.

His major priorities were housing and public health and he immediately became a member of the Health and Housing Committee.

An issue for the coal industry in the 1920s was increased foreign competition. It was Bevan’s opinion that Chancellor of the Exchequer Winston Churchill made some questionable decisions. Among them was the decision to adopt the gold standard at the prewar parity. Savers were protected, but the rate chosen affected exports and needed high interest rates to support it.

The coal-owners and the workers clashed over the prospect of longer hours and lower wages. The Trades Union Congress (TUC) announced a General Strike on May 1, 1926. The strike lasted seven months. Bevan became chair of the Council of Action and was largely responsible for organizing the distribution of food. Negotiations failed between the coal owners and the miners. District agreements in each area were made, rather than any form of collective agreement.

3. Finest Works

After the failure of the 1926 General Strike, Bevan concluded that power rested in Parliament. In 1929, Bevan was elected as a member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons for Ebbw Vale.

He had won a seat on the Monmouthshire County Council in 1928 and faced a dual responsibility. He decided not to resign his position on the Council. He retained it until he was unseated in 1931. Later, he was re-elected in 1932. He chose not to run in the 1934 election. Bevan missed numerous Council meetings because of his commitments in Parliament. However, he gained some insight into the chronic underfunding of local government and its inadequacy in dealing with the issue of health.

Bevan was a passionate spokesman for the plight of the unemployed. He believed there were inequities in the methods in which the unemployment insurance was administered. He was a staunch critic of anyone he felt opposed the working man and woman, including members of his own party.

In 1934, Bevan married Janet Lee, known as Jennie Lee. She was a Scottish politician and a Labour member of Parliament. She served in a by-election from 1929-1931 and from 1945-1970. During the late thirties and early forties, Bevan succeeded in having himself ‘misunderstood,’ ‘maligned,’ or ‘mistrusted.’ In 1936, he joined the board of the new socialist newspaper, Tribune. He was a Socialist and believed in working class unity. However, many of his articles appeared to some that he was sympathetic toward Communism.

Bevan’s rebellious behavior led his party to expel him in 1939 from March to November. He appealed and was readmitted in December 1939.

Bevan was critical of the British government’s rearmaments plan. He was particularly critical of Winston Churchill’s government’s foreign policy and at one point made a motion to censure him. Churchill had public support and Bevan’s vitriolic attacks on him angered Churchill’s supporters to a point that parcels filled with excrement were often sent to his home.

Bevan voted against his own party’s stance on new defense regulations. This did not go over well with party officials and he was cautioned about voting against his own party.

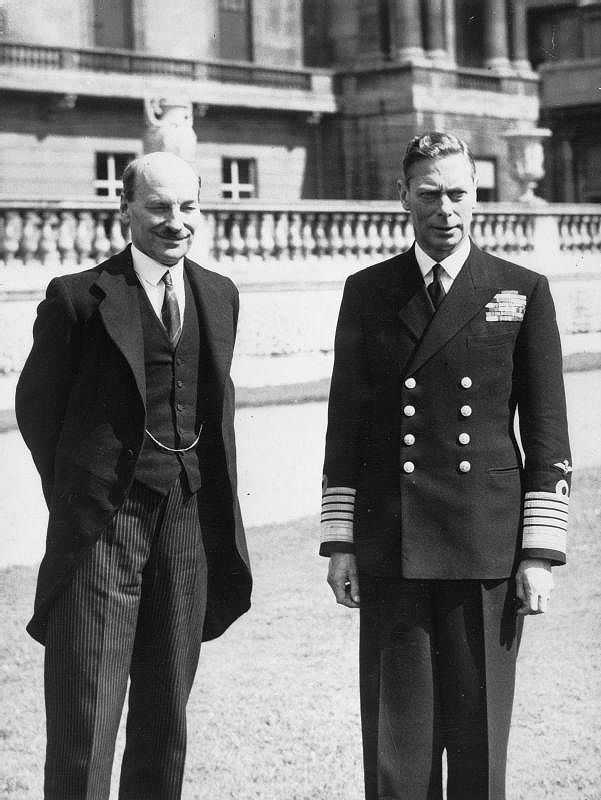

In 1945, the Labour Party won a landslide victory and had a large enough majority to present some far-reaching social reforms dubbed the “Welfare State.” Clement Attlee was elected Prime Minister. Bevan was appointed Minister of Health. His charge was to institute a new and comprehensive national health service.

Inspired by the Tredegar Medical Aid Society, Bevan led the establishment of the National Health Service. The National Health Service Act of 1946 was passed and became effective July 5, 1948. This law nationalized more than 2500 hospitals within the United Kingdom.

In 1951, Bevan was named Minister of Labour, but he resigned after two months when the Attlee government proposed the introduction of prescription charges for dental and vision and decided to transfer funds from the National Insurance Fund to pay for rearmaments.

In 1952, Bevan wrote In Place of Fear. The book sold well, but the reviews were less favorable. The Times Literary Supplement termed the book a ‘dithyramb’. Yet, some biographers consider it a classic socialist tract.

Attlee retired in 1955. Hugh Gaitskill succeeded him. Bevan and Gaitskill had often disagreed, but Gaitskill appointed Bevan as Shadow Colonial Secretary. Bevan was critical of this post. He believed Britain should treat people around the world as equals, not subordinates. In 1956 he was appointed Shadow Foreign Secretary. In this post he was critical of the Egyptian President Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein’s seizure of the Suez Canal.

In 1959, Bevan was elected Deputy Leader of the Labour Party. His tenure was short-lived as he developed stomach cancer and died.

4. The Legacy

Bevan experienced, as a young man, the effects of poverty and unemployment and the impact it could have on the quality of life. He believed that homes, health, education, and social services were birth-rights.

Bevan’s father died of pneumoconiosis, a miner’s disease caused by the lungs’ inhalation of dust. It is possible that Bevan had some experience with the 1918 Spanish Flu. Miners, particularly those in the pits, were among the hardest hit.

The National Health Service was Bevan’s most important contribution to the United Kingdom. The agency is reputed to be more popular than the monarch, the BBC, and the military. Currently, in 2020, the world is experiencing another pandemic and the services of the NHS have been a godsend.

Bevan died on July 6, 1960 at his home in Asheridge Farm, Chesham, Buckinghamshire. His remains were cremated at Gwent Crematorium in Croesyceiliog in a private family ceremony.