1. Early Life

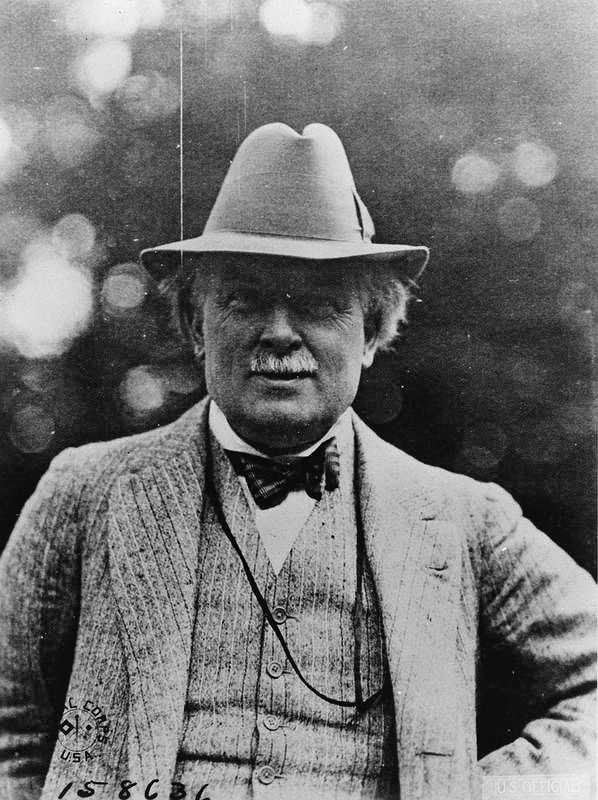

David Lloyd George was born on the 17th January 1863 In Manchester. His parents were William and Elizabeth George, William having moved to Manchester from Pembrokeshire in his profession as a teacher.

Sadly William George died when his son was only a year old and David Lloyd George’s mother took the family to live with her brother Richard Lloyd in Caernarvonshire, having been left in a state of poverty. Richard was a big influence on the young David, helping to oversee his education and although born David George, the future Prime Minister would add his uncle’s surname of Lloyd to his own.

Encouraged by his uncle, David Lloyd George set out on a career in law at the age of 14, becoming articled in 1879 to a firm of solicitors in Porthmadoc. In 1884 David Lloyd George passed his final examinations and the following year he set up his own law practice from his Uncle’s house.

Under the influence and further encouragement of his Uncle, Lloyd George was also developing an interest in politics and campaigned for the Liberal party in the 1885 election. Five years later in 1890 Lloyd George stood himself at a by-election for the Caernarvon Boroughs seat, where he won by a small margin to take his place in Parliament.

2. Early Career

Although elected to parliament Lloyd George continued with his law practice, merging in 1897 with Arthur Roberts.

Yet his talent for speaking and debate was not going unnoticed in Westminster, where he became a prominent member of the more radical side of the opposition Liberal party. He was not afraid to speak up for what he believed in and was vocal in his opposition to the war in South Africa in 1901.

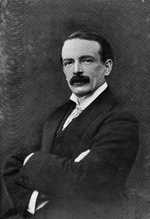

In 1905 the Liberals moved from opposition in to government under the Premiership of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman and Lloyd George received his first cabinet post as President of the Board of Trade.

In this role Lloyd George introduced the Merchant Shipping Act of 1906 which improved food standards and accommodation through regulation for seamen. On the flip side Lloyd George also raised the Plimsoll Line which endangered lives by allowing new cargo vessels to increase capacity by 5%.

Campbell-Bannerman died in 1908, to be replaced as Prime Minister by H.H. Asquith, with Lloyd George appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer. A year later he produced the ‘people’s budget’ which provided for social insurance, but it was rejected by the House of Lords.

Lloyd George persevered and returned in 1911 with the National Insurance Act, introducing contributory schemes of health and unemployment insurance based on similar schemes he had seen while on a visit to Germany. It was not a universally popular scheme, but Lloyd George was a skilled parliamentarian who saw his act passed and with it the early foundations for the welfare state were laid.

Further radical reforms of the time included the Old Age Pension Act as Lloyd George looked to improve the lot of the poor who were too old to work.

3. A War Time Prime Minister

David Lloyd George was a self-confessed pacifist but as war became almost inevitable in 1914 he focussed on the financial implications and the need to increase the production of munitions.

He was appointed minister of munitions and brought his reforming zeal to the problem at hand. By utilising help from big business and organised labour Lloyd George proved a huge success at his ministry and greatly contributed to eventual victory. In 1916 he was appointed secretary of war before replacing Asquith as Prime minister in December of that year.

Lloyd George came to power with the backing of leading Conservatives, with many of the main players in his own party having resigned with Asquith. He quickly trimmed the War Cabinet to 5 people under his chairmanship from the previous 23 in order to stop lengthy discussions and to make quicker decisions.

Lloyd George was already popular with the population at large, if not the generals with whom he often disagreed with on tactics. In 1917 Lloyd George persuaded a reluctant Admiralty to employ a convoy system to help protect shipping which was bringing food in to the country, combatting the enemy submarines threatening to starve the country out of the war.

The mistrust between Lloyd George and his commanders in the field remained, but in 1918 after the Germans nearly pushed through a successful offensive a unified allied command was formed under Marshal Ferdinand Foch. The tide of the war was soon to turn and an exhausted and defeated German army were forced to agree to the armistice in November.

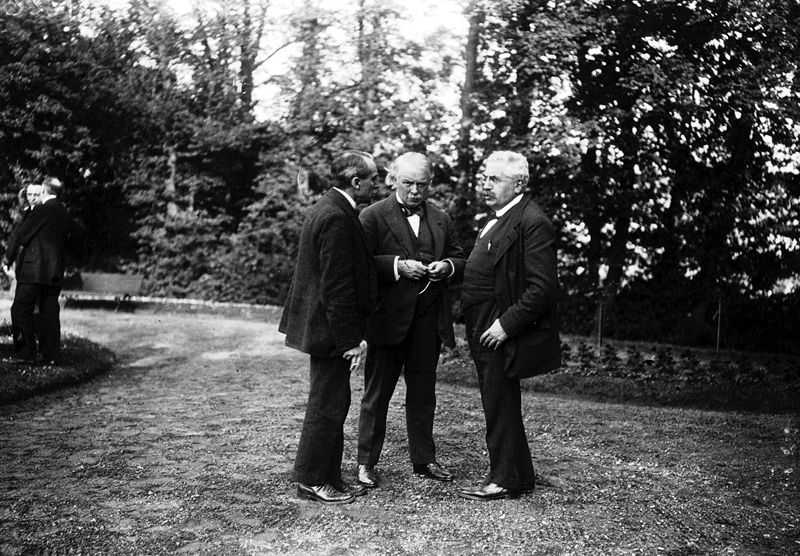

David Lloyd George was Britain’s chief delegate to the Paris peace conference which oversaw the drafting of the Versailles Treaty. Not surprisingly he won a huge majority at the 1918 general election, though still as head of a coalition with his Conservative partners.

4. Later Life

In 1918 David Lloyd George introduced the Representation of the People act, expanding the vote by removing property qualifications, before turning his attention to Ireland.

Since 1919 the Anglo-Irish War had been raging and the decision was taken to reverse a policy of repression and seek a truce. This led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 and the creation of the Irish Free State.

However, Lloyd George’s government was starting to run on borrowed time after an ‘honours for sale’ scandal added to increasing criticism of his foreign policy. This came to a head in the Canak incident when the Conservatives in the coalition did not agree with the position taken by Lloyd George which threatened to take Britain to war with Turkey over an area in the allied occupied territories of that country. When in October 1922 the Conservative party voted to fight the next election independently and not as a coalition, David Lloyd George resigned.

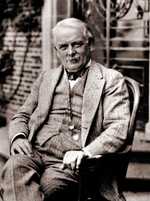

Lloyd George never held high office again, although he did lead the Liberal party between 1926 and 1931. He continued to champion progressive causes and was offered a war cabinet post by Winston Churchill in 1940, which he declined due to ill health. He took up a position in the House of Lords as Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, but he died not long after on the 26th March 1945, a couple of months short of seeing the second world war end in Europe.

5. His Legacy

Although David Lloyd George never returned to high office after his resignation in 1922, his place in British history was assured following World War One.

He was the first Welsh speaker to hold the office of Prime Minster and the last to date to represent the Liberal party.

Yet his radical social changes have had just as lasting and as important an impact on Britain, including an act which allowed women to sit in the House of Commons. His raft of measures, combined with his leadership in the war, makes Lloyd George one of the most significant public figures of the 20th century.

However it was not all plain sailing. As well as the later ‘honours for cash scandal’, Lloyd George’s political career nearly came crashing down two years before the outbreak of the first world war.

He was accused of corruption in profiting from the purchase of shares while aware a government contract was going to be awarded to the Marconi Company to build wireless communication stations. He was ultimately cleared of the charge of corruption, although the parliamentary enquiry did find he had profited from his dealings.

Away from politics Lloyd George married Margaret Owen in 1888 and they had five children. He would suffer immense personal tragedy in 1907 with the death of his daughter Mair, aged just 17 years old. His wife Margaret died in 1941 but in 1943 Lloyd George married Frances Stevenson who had become his private secretary when he was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer.