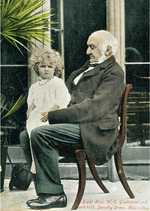

1. Gladstone's early life

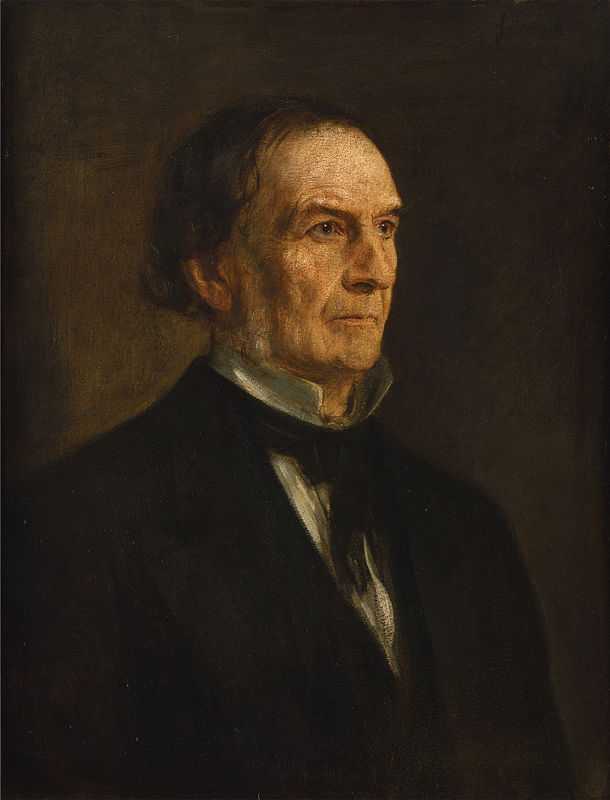

William Ewart Gladstone was born on December 29, 1809 in Liverpool. He was the fourth son of John, a wealthy merchant, and his second wife, Ann MacKenzie Robertson.

Gladstone’s formal education began in 1816 at St. Thomas Anglican Church in Seaforth, a church his father built. Reverend Mr. Rawson, an Evangelical Vicar, was imported from Cambridge to tutor him. Gladstone and eleven other boys were taught in the parsonage.

In 1821, Gladstone enrolled at Eton. Sports were Gladstone’s major pursuits. In the spring of 1822, Dr. Edward Craven Hawtrey came into his life and provided him with the incentive to learn and succeed. Gladstone became a voracious reader.

He read the classics, poetry, and the bible. He kept a diary and recorded everything he read. His other interests included debating and writing for the Eton Miscellany, the school newspaper.

In 1828, Gladstone entered Christ Church Oxford. His recreational pursuits were conversation and debating. He worked hard at his studies, focusing on the classics and mathematics.

In the late summer of 1831, Gladstone took five days off to visit London. He listened to over fifty hours of debate in the House of Lords and perfected his talent as an orator. His oratorical skills served him well as he later became president of the Oxford Union. He was a highly successful undergraduate which led to him earning a double first-class degree.

2. Early career

Gladstone left Christ Church Oxford in 1831. Shortly thereafter, the Duke of Newcastle asked him to represent the borough of Newark in Parliament.

In 1833, Gladstone, a Tory, took his seat in the House of Commons. His first speech was a response to the slave question. The proposed bill went through several stages, but, finally, a bill was introduced to gradually abolish slavery, preceded by an intermediate stage designated as an apprenticeship to last seven years.

The planters were to be given a gift of twenty million pounds. Gladstone’s father was a slave owner and the manager at his father’s Demerara estate in the British West Indies was directly attacked. He was labeled as a murderer of slaves because the slaves were systematically worked to death in order to increase the crop.

Gladstone defended his father’s interests as well as his name. Later, voters, newly enfranchised by the Reform Act of 1832, prompted Parliament to approve the Emancipation Act. Twenty million in compensation was given to the West Indian planters and a proscribed period of apprenticeship for slaves under age six. Abolitionists documented the continued abuses and were able to bring about slavery’s early demise. By August 1, 1838, slavery ended in the British West Indies.

In 1834, Sir Robert Peel became prime minister. He sent for Gladstone and offered him a Junior Lordship of the Treasury. The next year he gave him the more important post of Under-Secretary for the Colonies. This post was short-lived as an issue involving the Irish church came up and Peel was defeated. He resigned.

In 1838, Gladstone wrote a book The State in its Relations with the Church. The book was not highly regarded. Later, he blamed the ideas that he had set forth in his book on youthful ignorance.

He also realized in 1839 that he didn’t want to be a barrister as he had thought in 1833 and had his name removed from the roster at Lincoln’s Inn. In that same year his thoughts turned to marriage. He renewed his acquaintance with Catherine Glynne, daughter of Sir Stephen Glynne of Hawarden. They married and over the next fifty-nine years they had eight children.

Ironically, Catherine was the only one who had read his book in its entirety. The marriage gave him a secure base of personal happiness and established him in the aristocratic governing class of the time. He moved to Hawarden where he spent the rest of his life.

In April 1840, Gladstone denounced the Opium War which Henry Temple Palmerston, 3rd Viscount, had waged against China. The motivation for his speech was different than his speech in support of the West Indian sugar planters. Unlike slavery, Gladstone believed that England would be judged by God for its injustice towards China.

In 1843 Peel offered Gladstone the position of President of the Board of Trade. He was responsible for the Railways Act of 1844. Public railroads had been in existence in Britain since 1825. Gladstone’s bill introduced unique regulation strategies, significant of which was the regulation of the newly invented electric telegraph lines that ran alongside the railroad.

The repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 was Peel’s downfall. Insufficient attention had been given to the Irish potato blight and millions of lives were lost. Peel’s departure divided the conservatives. Gladstone took over and became known as a Peelite. His career in conjunction with a coalition of Whigs under the leadership of Lord Aberdeen would take a decided turn.

3. Greatest Achievements

From 1852 to 1855, 1859-1865, and 1865-1866, Gladstone held the position of Chancellor of the Exchequer.

He simplified Britain’s tariffs of duties and guided Britain through the Crimean War in 1853-1856. Rather than borrow money to fund the war, he raised the income tax.

During his second term as Chancellor of the Exchequer, he was the leader of the Liberal Party and with the help of Richard Cobden, he was able to secure a free trade treaty with France which resulted in the gradual reduction of the income tax.

In 1865 he advocated for the enfranchisement of the working classes in the towns. His reform bill was rejected by a small faction in the Liberal Party. Benjamin Disraeli and the Conservatives saw an opening and got the Second Reform Act of 1867 passed.

In 1868, Gladstone was selected to serve as Prime Minister. In his first session, he disestablished and disendowed the State Church in Ireland, reformed the rights of the Irish tenant, established a system of national education, and passed the Ballot Act. Also, he introduced a bill to improve the condition of university education in Ireland.

The Catholics in the House of Commons weren’t satisfied and voted against it. The Conservatives won the majority. In 1874, Gladstone resigned.

The Liberals won in 1880 and Gladstone became Prime Minister again. He faced an impending war in the Sudan and South Africa, agrarian revolution in Ireland, and the uncompromising actions of the Home Rule party in the House of Commons. The Conservative Party finally cooperated with Gladstone and he was able to get through a few reforms.

Gladstone was committed to Ireland, but two men were assassinated in Dublin. He was slow to respond when military help was requested in the Sudan and General Gordon was murdered in Khartoum. The Conservatives and Irish members rejected a clause in the budget and Gladstone’s government was defeated and he resigned.

In 1886, he was reelected during the general election. He firmly believed that the Irish people were in favor of Home Rule, but his own party split on the issue and Gladstone was defeated at the next general election.

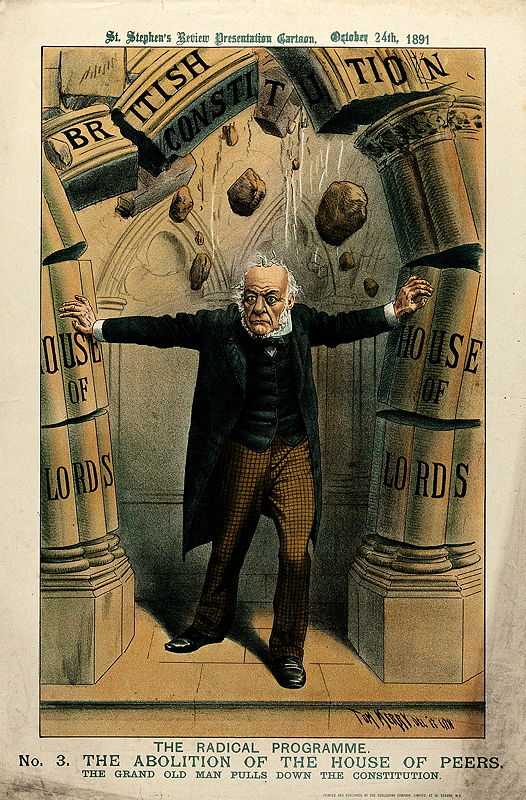

In 1892, Gladstone was reelected Prime Minister. After dealing with obstructionists, a Home Rule bill was passed in the House of Commons, but it was defeated in the House of Lords. Deeply frustrated, he resigned in 1894. He was eighty-four years old.

4. Gladstone's legacy

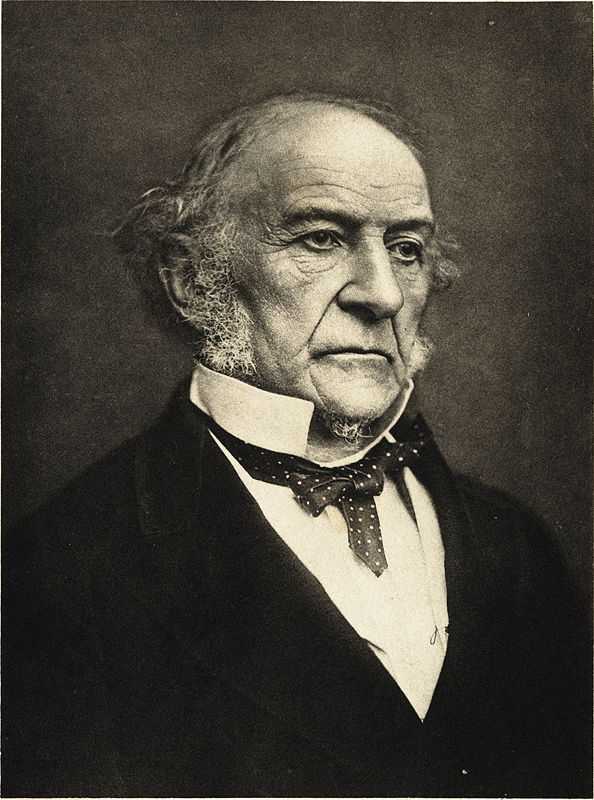

William Ewart Gladstone was a superior orator and statesman. His career was one of activity and labor. He left a successful record of practical legislation.

He had his ‘finger in every pot.’ The working class loved him and nicknamed him ‘The People’s William.’ His accomplishments in the world of finances and his style of campaigning in Midlothian set the standard for generations to come.

On May 19, 1898, Gladstone died at his home at Hawarden Castle and was buried in Westminster Abbey. On June 14, 1900, his wife died and was interred there by his side.

One of Gladstone's legacies is his list of famous quotes, including:

"No man ever became great or good except through many and great mistakes."

"Good laws make it easier to do right and harder to do wrong."

"Be happy with what you have and are, be generous with both, and you won't have to hunt for happiness."

"We look forward to the time when the Power of Love will replace the Love of Power. Then will our world know the blessings of peace."

"Justice delayed is justice denied."