1. The Duke's Early life

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington was born 1st May, 1769, in Dublin in to an aristocratic Anglo-Irish family.

Along with his younger brother, Wellesley attended Eton in 1781, the same year in which his father died. The death resulted in financial difficulties for the family and Wellesley, who was not showing great promise at Eton, was withdrawn from the school by his mother in 1784.

From there he was sent to a military academy in Angers, France before he joined the army in 1787, with one of his early appointments as aide-de-camp to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

Wellesley gradually climbed the ranks within the army, while also beginning his political career by becoming an MP in the Irish House of Commons at the age of 24. However, over in France a revolution was about to take place and the execution of King Louis XVI in January 1793 shook the British establishment to the core and the two countries were soon at war.

Wellesley was now commanding officer of the 33rd Foot and he would get his first taste of action against the French in 1794 during the Flanders campaign.

The French were to be victorious on this occasion, but Wellesley had observed his superiors and would learn from the mistakes he had witnessed.

2. A Rising Military Career

After Flanders Wellesley was posted to India in 1796, where he was to experience early military successes.

Following the defeat of Tipu Sultan, the ruler of Mysore in 1801, Wellesley won a notable victory in a battle at Assaye two years later against a Maratha Empire army which was threatening to raid in to Hyderabad. Knighted for his efforts he could now return to England in 1805 with his name made. Back home he entered Parliament and married Kitty Packenham, who he had first proposed to in 1793, a proposal rejected by her family at the time due to his young age and poor finances.

Wellesley was appointed chief secretary for Ireland and his thoughts on state affairs and particularly the military were being listened to. When Spain chose to revolt against Napoleon's French occupation Wellesley was the choice to take command of British forces on the Iberian Peninsula in support of the Spanish and Portuguese. By 1812 he was in a position to lead his army in to Spain and won a famous victory at Salamanca, before going on to take Madrid.

Wellesley’s army was forced to retreat to Portugal once more, where they regathered before crossing in to Spain again in 1813. In June the combined forces from England, Spain and Portugal clashed with their French counterparts at Vitoria. It was to prove the decisive battle of the Peninsula War, with the French eventually retreating to Pamplona, though with heavy losses on both sides.

The spoils of war were too tempting for many of the victors as the French abandoned much of their baggage, with the level of looting helping the French to escape. It led to one of Wellesley’s most noted remarks when he called his drunken troops “the scum of the earth”.

3. Waterloo, 1815

Following his defeat in the Peninsula War Napoleon was forced to abdicate and Wellesley earned a new title, the Duke of Wellington.

He was made ambassador to France and represented his country at the Congress of Vienna, called to re-organise Europe following the Napoleonic Wars. However this was not the last Europe was to see of Napoleon Bonaparte who escaped from his exile in Elba in February, 1815. After landing at Cannes with 1,500 men he gathered support and entered Paris a week later as Louis XVIII fled to Ghent.

It was at Waterloo in Belgium on the 18th June that the Duke of Wellington won the battle which was to permanently enshrine his name in the annals of history. He was in command of an allied army, but Napoleon had already forced the Prussians to retreat and on that fateful day in June his forces outnumbered Wellington’s by around 4,000 men.

The ensuing battle was fierce, but the allied army stood firm against the onslaught from the French. The tide was turned when the Prussian army under General Gebhard von Blucher reached the battle and the French, now heavily outnumbered themselves, fled the field.

The Duke of Wellington had helped stop Napoleon’s march across Europe and ensured Britain’s role as a key player on the continent. Napoleon Bonaparte was exiled once more, this time to the remote island of St Helena, yet the cost of victory had been heavy in casualties. Wellington reflected on “the terrible loss” suffered, writing “I hope to God that I have fought my last battle”. Following the battle he remained in France until 1818 as commander of the British army, before returning home as a national hero where he returned to politics and joined the government under Lord Liverpool.

4. The Call to High Office

At home the population was experiencing tough economic times and political unrest was growing with increasing demands being made for political reform to allow the ordinary people a vote.

Wellington was not at all progressive on this issue and neither was the government he served. Four years after the Battle of Waterloo a demonstration in St Peter’s Field in Manchester demanding parliamentary representation was charged by troops. Known to posterity as the Peterloo Massacre, 18 unarmed civilians were killed and around 650 injured. Politically the Duke of Wellington was now in opposition to the wishes of much of the ordinary working population.

These demands for reform refused to go away and in 1828 King George IV turned to the Duke of Wellington to become Prime Minister. He dutifully accepted the position even though it would be beset with difficulties and animosity between different factions within his own Tory party.

Although he could still not accept parliamentary reform, Wellington had acknowledged prior to his appointment as Prime Minister the need for Catholic emancipation. Catholics were barred from holding public office, but against the opposition of some in his own party he passed the Catholic Relief act in 1829, providing Catholics with civil rights.

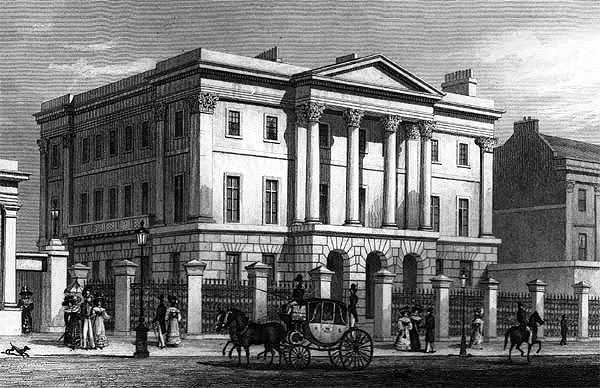

This proved to be one of the main achievements of his time as Prime Minister as he believed it was for the greater good. However his opposition to reform saw his popularity fall heavily, to the point he needed to place iron bars on his London home, Apsley House, to prevent the windows being smashed by angry crowds.

Wellington’s position as Prime Minister became untenable after defeat in the House of commons and he duly resigned his office in November 1830. And so one of our greatest military leaders also features on our list of the 10 Worst Prime Ministers!

5. Retirement and Legacy

The Reform bill was finally passed in 1832, although Wellington initially continued with his opposition.

He eventually relented and asked his supporters to stay away from Parliament to allow the bill to pass, recognising the country had reached a stalemate on the issue. In 1834 he accepted the position of Foreign Secretary under Sir Robert Peel and later leader of the House of Lords, before he retired from politics in 1846.

The Duke had lost his wife, Kitty, in April 1831. Twenty one years later, on the 14th September 1852, the great military commander from the Battle of Waterloo died following a stroke. As Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports he had a residence at Walmer Castle in Kent which had become his favourite and it was here he passed away. The huge crowds which came out on to the streets to watch his coffin pass as the Duke made his way to his final resting place in St Paul’s Cathedral proves they had not forgotten his military service for the country. Indeed Tennyson’s “Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington” emphasised the stature he still retained.

Wellington was a man of honour who liked strict discipline. Being Prime Minister did not stop him challenging the Earl of Winchilsea to a duel in 1829 after the earl offended him during the debates over Catholic emancipation. It is claimed the Duke aimed to miss, while the Earl decided not to fire at all and honour was saved all round, although Winchilsea still wrote an apology to the Duke.

The Duke of Wellington will forever be known to most for his role at the Battle of Waterloo. Others will continue to automatically associate him with the much loved Wellington boot, originally a leather boot worn at the time by the aristocracy.

Queen Victoria left no doubt how she thought he should be remembered, saying of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington in a letter,

“He was the greatest man this country ever produced, and the most devoted and loyal subject, and the staunchest supporter the Crown ever had.”