1. Early life

Roger Gilbert Bannister was born on March 23, 1929 in Harrow, England. He was the son of Ralph Bannister, a clerical officer at the Board of Trade in London, and his wife Alice Duckworth.

In 1935, Roger entered Harrow Elementary School. It was a mixed public school. His classroom was large and seldom had fewer than fifty students.

Roger’s parents valued serious reading. He and Joyce, his only sibling and older sister, were not permitted to read comics or dramatic children’s books. Only books of the ‘look and learn’ variety were in his family’s library.

When World War II started on September 1, 1939, every family in Roger’s town was issued gas masks and instructed to go to the shelters where emergency food rations were stored inside. The government imagined that London would suffer a huge number of casualties through gas attacks and bombing. Plans were made to send as many government departments as possible to safer cities. Roger’s father’s department was relocated in Bath.

There were no openings in the historic Bath Grammar School and Roger was offered a place at the Bath City Secondary School. It was there that he took an interest in cross-country running. He won the junior cross-country cup three times.

In 1942, Roger’s house was damaged during an attack on Bath. After two nights of bombings, Roger’s parents, along with other families, took him and his sister and camped in the woods overnight. Several hundred people were killed.

As a result of his high grades, Roger won a direct grant place to University College School (UCS) in Hampstead. His family returned to London even though it was being bombed again. Realizing that he was at a disadvantage since he began at UCS halfway through the term, Roger made full use of the UCS and the Harrow public libraries.

Rugby, cricket, and rowing were the three sports played at UCS. Occasionally, when the ground proved too hard to play rugby, UCS created an impromptu sports day. Roger entered a half-mile race and won by some thirty yards.

In January 1946, Roger sat for his Cambridge scholarship exams and was accepted. As a result of an unsavory ploy by a St. John’s College tutor, Roger was diverted to Oxford. Early in 1946, Roger received a handwritten acceptance letter from the Rector of Exeter College, Oxford offering him a place at the college to read medicine.

2. Early career

Roger arrived at Oxford in early October 1946. One of the first things that he did was join the university athletic club. He knew he wanted to be a runner.

An Exeter groundsman made an invidious comparison between him and Jack Lovelock, a great miler for Oxford, and he was snubbed by the middle-distance coach for Oxford.

These slights hurt, but Roger was not discouraged. He came in second in the freshman’s mile race in November of that year with a modest time of 4 minutes 52 seconds. The loss was disappointing, but he was satisfied that he was on his way and began to run some cross-country races.

On March 22, 1947, Roger was selected as the third string for Oxford in the mile race against Cambridge at White City Stadium. It was during this race that he tapped a hidden source of energy that he always suspected he had and won the race by twenty yards in a time of 4 minutes and 30.8 seconds.

Combining his studies and sport was a struggle, but Roger got involved in Oxford sporting administration where he served as secretary and then as president of the University Athletic Club. Roger’s first action as president was to propose a scheme to replace an uneven third-of-a-mile long university track at Iffley Road with a new quarter-mile track, meeting international standards.

Inexperienced and unwilling to consult the university surveyor for fear the project would get stuck in university committees, Roger accepted the lowest bid. The contractor went bankrupt and Roger had to find another firm. All of this impacted on the soccer team’s ability to play. They had to rent another field for the whole of the next season. Roger’s project was completed three months late, but when the soccer club used the new field, it remained a force in national amateur soccer for several years.

In 1948, Roger was designated as an Olympic “possible.” He declined. He felt he couldn’t compete at that level. He set a goal for the 1952 Olympics at Helsinki.

In 1949 and 1950, Roger experienced some successes and failures. He improved his time in the 880-yard race with a time of 1 minute and 52.7 seconds and won several mile races, with a time of 4 minutes and 11 seconds. Without the necessary training, he came in third at White City with a time of 4 minutes and 14.2 seconds. After that disappointment, he realized that he needed to train harder and more seriously.

In 1951, Roger won the Penn Relays mile race in 4 minutes and .08.3 seconds. Later, in the same year, he won the mile race at the Amateur Athletic Association (AAA) Championships in White City with a time of 4 minutes and 07.8 seconds. His time set a meet record.

Roger became serious about entering the 1952 Olympics. He began a systemized plan of training, including high intensity workouts and hill running. At the 1952 Olympics, he set a British record for the 1500 metres race (1.5 kilometers or 15/16 miles) at 3 minutes and 46.30 seconds, but he came in fourth.

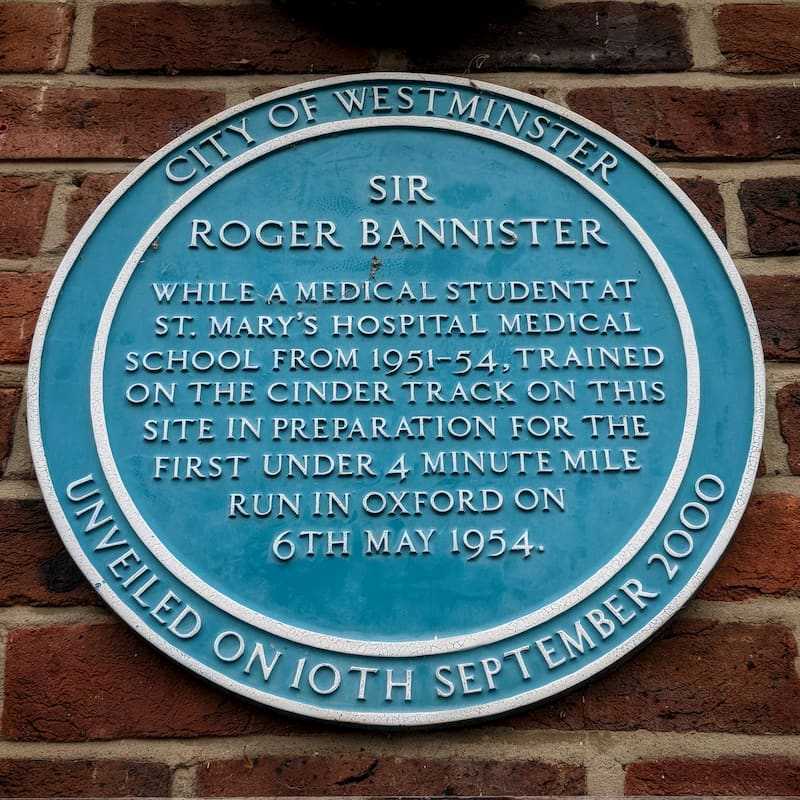

Roger was disillusioned by his performance at the 1952 Olympics, yet, he realized the possibility of running the mile in under four minutes. American Wes Santee and Australian John Landy had the same idea. However, assisted by coach Franz Stampfl and Christopher Chataway and Chris Brasher as his pacemakers, Roger beat Landy on May 6, 1954 in a meet between British AAA and Oxford at Iffley Road Track in Oxford. His time was 3 minutes and 59.4 seconds. Later, Landy broke Roger’s record with a time of 3 minutes 57.9 seconds.

On August 7, 1954 at the British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Vancouver, B.C., billed as “The Miracle Mile,” Roger competed against Landy and won with a time of 3 minutes and 58.8 seconds.

In that same month, Roger ran his last race: 1500 metres in Bern, Switzerland with a time of 3 minutes and 43.8 seconds. Shortly thereafter, Roger retired from athletics and focused on his work as a junior doctor and a career in neurology.

In 1954, Roger met Swedish artist, Moyra Elver Jacobsson during the summer of “The Miracle Mile” race. After he graduated from St. Mary’s and passed his medical board exams, they were married in 1955 in Basel, Switzerland. They had four children.

3. The legacy

Roger Gilbert Bannister was an extraordinary man. He didn’t allow sports pundits to unduly influence him.

Running races for eight years was “what he did.” It was not “who he was.” He knew he wanted to be a neurologist.

Roger was a member of the Royal College of Physicians (FRCP). He published more than eighty papers on the autonomic nervous system, cardiovascular physiology, and multiple system atrophy. He also edited Autonomic Failure: A Textbook of Clinical Disorders of the Autonomic Nervous System with C. J. Mathias and five editions of Brain and Bannister’s Clinical Neurology.

In 2011, Roger was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. He died on March 3, 2018 at Oxford.