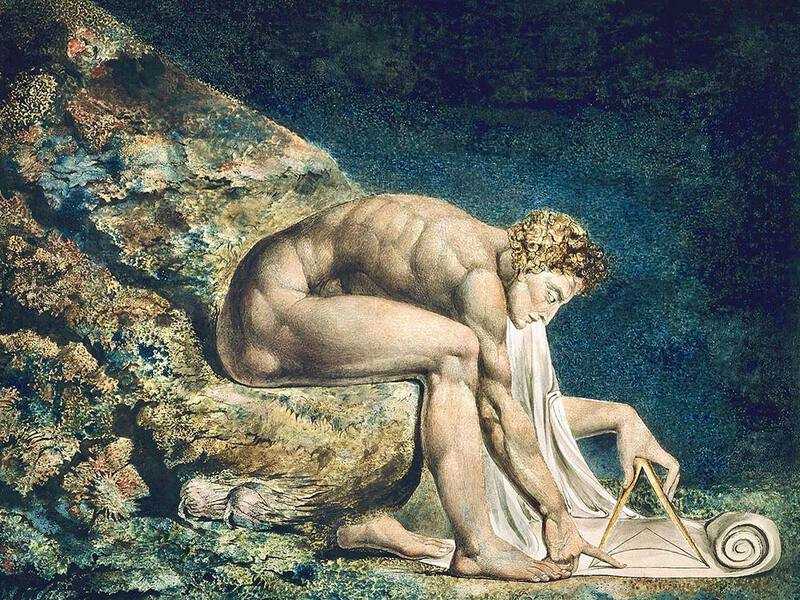

1. Isaac Newton (1642-1727)

Sir Isaac Newton was a polymath who excelled in the fields of mathematics, physics, and astronomy.

Until the age of twelve, Newton was homeschooled by his mother and grandmother.

Early life

From 1654 to 1659, he attended The King’s School in Grantham. In 1661, he entered Trinity College, Cambridge and earned his BA in 1665. In that same year, Britain was struck with the Black Plague and his college closed for two years.

During that time, Newton conducted private studies at home, discovering the generalized binomial theorem and developing a mathematical theory that later became calculus. He also explored optics, experimenting with prisms and investigating light.

Cambridge and politics

Newton returned to Trinity in 1667 and was appointed a Fellow. In 1668, he invented the first ‘working’ reflecting telescope. In the following year, he became a Lucasian Professor of Mathematics.

Interesting fact...

Newton didn't have much time for personal relationships and many think that he died a virgin. It is likely that he suffered from Asperger's Syndrome.

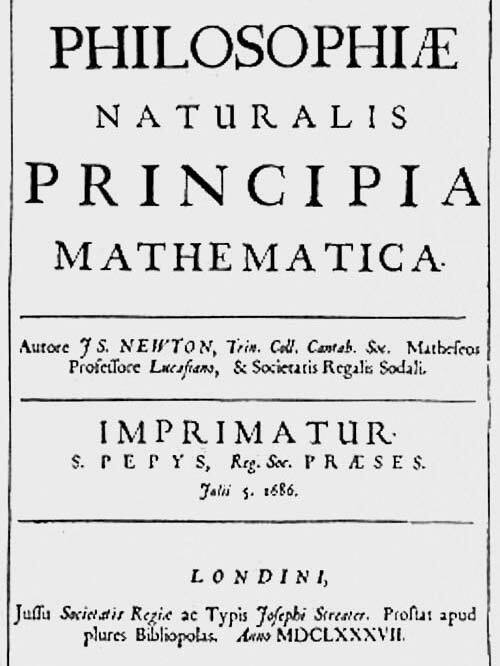

Between 1672 and 1687, Newton was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and laid the foundation of classical mechanics with the publication of his book Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy in 1687 (commonly referred to as the ‘Principia’).

Newton served two brief terms as a Member of Parliament (MP) for Cambridge, 1689-90 and 1701-02. He was placed in charge of the Royal Mint: ‘Warden’ from 1696-1700 and ‘Master’ in 1700. He resigned his positions at Cambridge in 1701.

Interesting fact...

There was one area where Newton was less successful: alchemy. He spent countless hours in his chemistry lab trying to turn elements into gold, develop a cure for any disease, and even come up with an elixir for eternal life.

In 1704, Newton expanded his studies in optics and published Opticks in 1704. In 1705, Newton was knighted by Queen Anne.

Greatest achievements

Newton's greatest achievements include:

- Inventing the reflecting telescope, which could magnify objects by up to 40 times.

- Discovering that sunlight is in fact made up of all the colours of the rainbow, by using refracting prisms.

- Founding calculus, a whole new branch of mathematics.

- Developing three laws of motion: those of inertia, acceleration, and action and reaction.

- Developing a theory of universal gravitation - that gravity applied to all things in all places - after seeing an apple fall from a tree.

2. Joseph Priestley (1733-1804)

Priestley was a chemist, and natural philosopher. Priestley attended local schools until the age of sixteen where he learned Greek, Latin, and Hebrew.

He was born into a ‘dissenter’s’ family and was prevented from entering an English University because of the Act of Uniformity (1662). Instead, in 1752, he matriculated at Daventry, a dissenting academy.

Priestly became interested in science in 1765 and wrote a history of electricity. He was accepted into the Royal Society in 1766 and began conducting his own experiments, including the conductivity of charcoal and the continuum between conductors and nonconductors. In 1767, he published The History and Present State of Electricity.

Priestley turned his attention to gases and is credited at the time with discovering oxygen. He also discovered a method for making carbonated water and published a pamphlet with Directions for Impregnating Water with Fixed Air in 1772. This work earned him the Royal Society’s prestigious Copley Medal in 1773.

Priestley’s tendency to combine his theological and scientific views frequently placed him in the middle of political controversy. His home was destroyed in Birmingham and he and his family were forced to flee Britain. They settled in the United States in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania. While there, he helped found the First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia.

Without input from Britain, Priestley’s scientific output was reduced, but he stimulated American interest in chemistry.

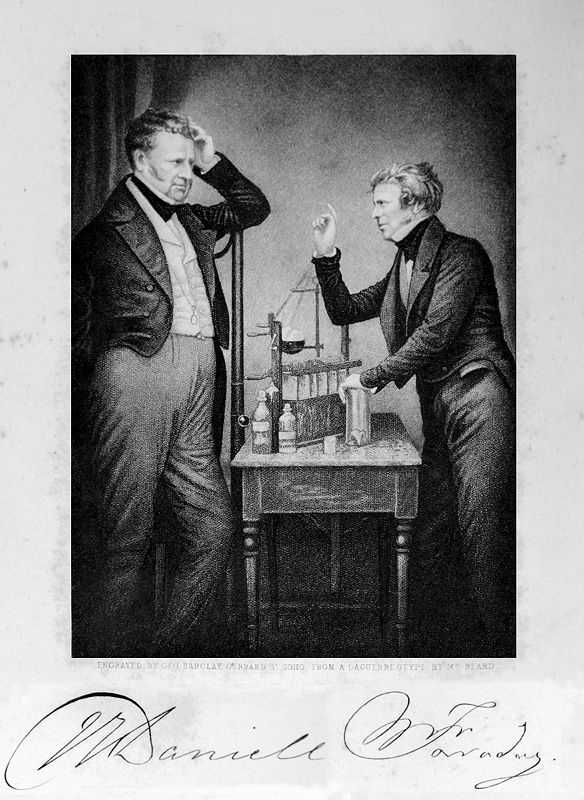

3. Michael Faraday (1791-1867)

Faraday was a physicist and chemist.

Until the age of fourteen, Faraday was taught the basics: reading, writing, and simple math at his church.

In 1805, Faraday became an apprentice to George Riebau, a local book binder and bookseller. He educated himself by reading many of the books in the store and developed an interest in science, especially electricity.

In 1812, Faraday began attending lectures by Humphry Davy, a chemist at the Royal Institution and Royal Society. He took notes and developed a 300-page book that he sent to Davy.

In 1813, Davy asked Faraday to be his chemical assistant. Together, they prepared nitrogen trichloride samples. By 1820, when Faraday ended his apprenticeship with Davy, he was well-versed in chemistry.

In 1821, Faraday experimented with electromagnetic rotation which signaled the first electric motor.

In 1824, Faraday was elected member of the Royal Society and in 1833, he was appointed the first Fullerian Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution.

Faraday also experimented with magnetic fields, He discovered that changing magnetic fields caused the production of electrical current in the nearby conductors. Further, he experimented with the laws of electrolysis, a process in which chemicals dissolved in a liquid breaks down when an electrical current is passed through the liquid with the help of electrodes.

Today, Faraday is regarded as the ‘father of electricity’ because all generators in power stations work on his discovered principles.

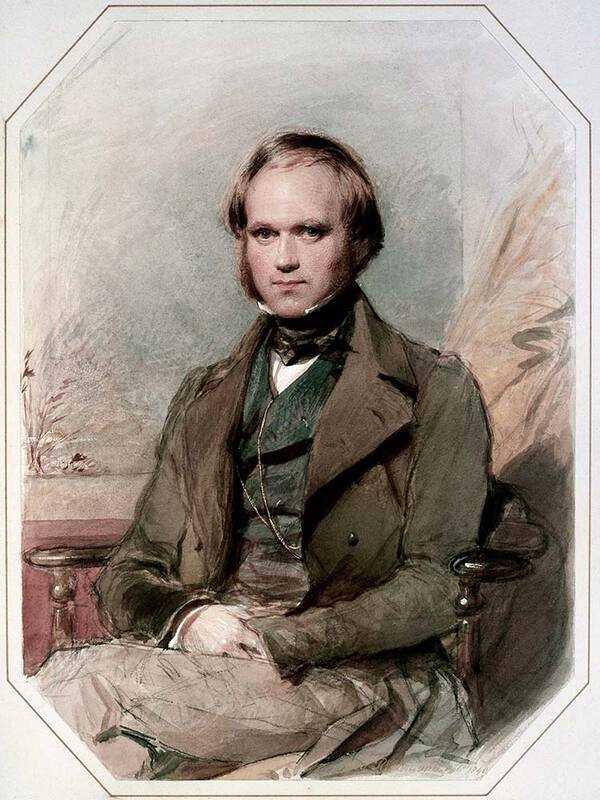

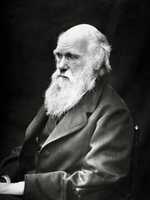

4. Charles Darwin (1809-1882)

Darwin was a naturalist geologist, and biologist.

At the age of eight, Darwin entered a Unitarian school run by its preacher. A year later, he joined his older brother at Anglican Shrewsbury School as a boarder.

In 1825, Darwin entered the University of Edinburgh Medical School. He didn’t find the coursework interesting and during his second year, he joined the Plinian Society which was a student natural history group. That experience led to the investigations of the anatomy and life cycle of marine invertebrates in the Firth of Forth.

In 1829, cognizant that his son did not want to be a doctor, Darwin’s father enrolled him in Christ’s College, Cambridge to earn a BA degree and become an Anglican country parson.

After Darwin earned his BA degree in 1831, he was offered a naturalist position aboard the H.M.S. Beagle. He returned home after five years. He brought with him a diary, notes, and sketches of his skins, bones, and carcasses. A year later, in 1837, he was appointed a new Fellow of the Geological Society. He began to develop a reputation through his publication of Geology and Natural History of the Various Countries Visited by H.M.S. Beagle in the Journal of Research in 1839.

For many years, Darwin portrayed himself as a ‘gentleman naturalist,’ while at the same time he was developing a revolutionary theory of evolution. He believed that species survived through a process called natural selection where those that successfully adapted to meet the changing requirements of their natural habitat thrived and reproduced and those that failed to evolve or reproduce died off.

In 1859, he published On the Origin of the Species by Means of Natural Selection. This ran contrary to the popular view of other naturalists at the time. Twenty years later, ‘evolution’ was accepted as fact by scientists and the public.

5. Joseph Lister (1827-1912)

Lister was a surgeon.

Until the age of nineteen, Lister attended two private Quaker schools; Benjamin Abbotts Isaac Browne Academy and the Grove House School. Both schools supported science and he was instructed in math, natural science, and language.

In 1848, Lister enrolled in the University College, London. In 1852, he received his Bachelor of Medicine, became a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, and was house surgeon at University College Hospital.

Between 1856 and 1861, Lister was appointed surgeon to the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary and the Glasgow Royal Infirmary. While working in the Male Accident Ward, he observed that 45-50% of his patients with open wounds, particularly amputations, were prone to sepsis and died. He began researching bacteriology and infection. He found an effective antiseptic in phenol (carbolic acid) in 1863 and from 1865-1869, surgical mortality was reduced in his ward from 45-15%. He published the results of his studies in a medical journal, The Lancet in 1867.

In 1869, he became Chair of Clinical Surgery at Edinburgh, but his discovery wasn’t widely accepted among the science community. He believed that it was important to get the acceptance of the London community. In 1877, he was appointed Chair of Clinical Surgery at King’s College. He had an opportunity to demonstrate his discovery and acquired acceptance when he performed a then revolutionary operation of wiring a fractured kneecap.

Lister was Queen Victoria’s surgeon. He was the first to become a British peer for services to medicine. In 1883, he became Sir Joseph Lister and later in 1897, he became Lord Lister of Lyme Regis.

Lister wrote no books, but he contributed many papers to professional journals. His observations, deductions, and practices revolutionized surgery throughout the world.

6. Alexander Fleming (1881-1955)

Fleming was a physician and microbiologist.

Fleming received his early education at Loudoun Moor School and Darvel School. When he was thirteen, he earned a two-year scholarship to Kilmarnock Academy. After moving to London, he attended the Royal Polytechnic Institution.

In 1903, Fleming enrolled in St. Mary’s Hospital School and three years later earned a combination Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) degree. He joined the research department at St. Mary’s and became assistant bacteriologist.

In 1908, he earned a Bachelor of Science degree in bacteriology and became a lecturer at the hospital until 1914. For the next three years, he served in World War 1 in the Royal Army Medical Corps.

After leaving the army, Fleming returned to St. Mary’s. In 1921, he discovered lysozyme, a substance present in tissues and secretions of the body which is capable of rapidly dissolving certain bacteria. This discovery would not be appreciated until the end of the twentieth century when it was learned that it was the first antimicrobial protein that constitutes part of the body’s innate immunity.

In 1928 Fleming made another discovery. As a result of a culture plate of staphylococcus aureus bacteria becoming contaminated by a fungus, he identified the mold as penicillium notatum and that it had inhibited the growth of the bacteria. The mold produced penicillin, an antibiotic.

Fleming’s discovery was not readily accepted, but it gradually started the antibiotic revolution and other scientists began to study its molecular structure. In 1945, Fleming shared the Nobel Prize with Howard Walter Florey, an Australian pathologist and Ernst Boris Chain, a German-born British biochemist.

Fleming received many awards. In 1944, he was knighted for his scientific achievements by King George VI.

7. Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin (1910-1994)

Hodgkin was a chemist.

Hodgkin attended St. John Leman Grammar School in Beccies, England and was one of two girls allowed to study chemistry.

Between 1928 and 1932, Hodgkin attended Somerville College, graduating with highest honors. In 1933, she began studying for her PhD at Newman College, Cambridge. She was awarded a research fellowship and earned a PhD in 1937 in x-ray crystallography and the chemistry of sterols.

Earlier in 1934, Hodgkin had contracted rheumatoid arthritis with deformities in both hands and feet, but she persisted in her goals: fellow, tutor, and reader. For her work solving the structure of steroids, penicillin, and vitamin B12, she was elected to the Royal Society. In 1964, Hodgkin received the Nobel Prize for her work with penicillin and Vitamin B12. In 1969, she discovered the structure of insulin

8. Francis Crick (1916-2004)

Crick was a molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist.

Crick’s initial education began at Northampton Grammar School. He received a scholarship to Mill Hill School, London when he was fourteen.

He studied math, physics, and chemistry. Later, he enrolled at University College, London (UCL) where in 1937, he received his Bachelor of Science degree. He began work on his PhD at UCL, but his studies were interrupted by World War II.

During the war Crick worked as a physicist in the development of magnetic mines for use in naval warfare. After the war, Crick switched from physics to biology. He resumed his studies at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge and worked in their research labs. Between 1947-49, he worked at the Strangeways Research Laboratory studying the properties of cytoplasm and the Cavendish Laboratory. Also, between 1949-50, Crick taught himself the mathematical theory of X-ray crystallography.

In 1954, Crick earned his PhD in X-ray crystallography of proteins. In 1951, James Watson started work at the Cavendish Laboratory. Crick and Watson began to do research together. In 1953, they published their research detailing the structure of DNA in the science journal Nature.

Enhancing their discoveries with the work of other scientists, particularly Maurice Watkins. Crick, Watson and Watkins won the Nobel Prize in 1962 in Physiology and Medicine for their determination of the molecular structure of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA).

In 1977, Crick moved to the United States and took a position with the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California. He made advances in science and technology, including screening for genetic disease, DNA fingerprinting, and genetic engineering.

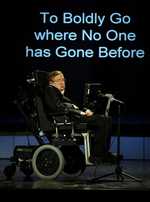

9. Stephen Hawking (1942-2018)

Hawking was a theoretical physicist and cosmologist.

Hawking began his primary education at Byron House School in Highgate and then, in his teens, he attended two independent (fee paying) schools; Radlett and St. Albans.

In 1959, at the age of seventeen, he won a scholarship to University College, Oxford, earning a Bachelor of Arts degree in physics and chemistry in 1962, followed by a Ph.D. in applied mathematics and theoretical physics at Trinity Hall, Cambridge in 1966.

In that same year, he was elected a research Fellow at Gonville and Caius College at Cambridge.

Hawking worked primarily in the field of general relativity (gravity), particularly on the physics of black holes, theorising that black holes emit radiation, often called ‘Hawking radiation’. This theory was controversial. In the late seventies, the discovery was widely accepted as a significant breakthrough in theoretical physics.

Hawking was the first to set out a theory of cosmology explained by the general theory of relativity and quantum mechanics.

In the early 1960s, Hawking contracted Lou Gehrig’s disease. Undaunted, Hawking became a Fellow at the Royal Society and wrote books that were a commercial success.

10. Tim Berners-Lee (1955-)

Tim Berners-Lee is a computer scientist.

He attended Sheen Mount Primary School and Emanuel School. At the age of eighteen, he enrolled in Queen’s College, Oxford and in 1976, he received his Bachelor of Arts degree in physics.

Berner-Lee’s first job was with Plessy Telecommunications, LTD as a software engineer. In 1980, for a short while, Berners-Lee was an independent contractor and worked for the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN). There he proposed a project based on the concept of hypertext.

He named it Enquire. In that same year, he began working for John Poole’s Image Systems, Ltd. He worked on ‘real time remote procedure calls’ which gave him experience on computer networking.

In 1984, he returned to CERN as a fellow. In 1989, he submitted a proposal based on the concept of the hypertext system that would make use of the internet. He named it the World Wide Web (www).

In 1994, in the United States, he established the WWW (W3) Consortium at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Laboratory for Computer Science.

In 2000, Berners-Lee co-authored with Mark Fischetti Weaving the Web: The Original Design and Ultimate Destiny of the World Wide Web and in 2004, he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II.

Berners-Lee’s invention is immeasurable. Instead of the small group he envisioned, he succeeded in connecting the world.

Learn more on our Tim Berners-Lee biography page.