1. Faraday's early life

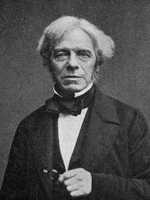

Michael Faraday was born September 22nd 1791 in Newington, Surrey, one of four children to James and Margaret Faraday.

His father was a blacksmith who had moved down from the North East of England to find work. However he struggled with his health which in turn affected his capacity to work, leaving the family with periods of poverty.

The Faraday family belonged to a Christian sect called the Sandemanians and it was through their Sunday school Michael Faraday learned basic reading and writing. From a young age Faraday was curious and eager to learn and he was to get an ideal opportunity to feed his curiosity at age 13. Faraday started work as a delivery boy for a bookseller, who must have realised the boy’s potential as the following year he made him an apprentice bookbinder.

Faraday would read the books he worked on with one in particular, Encyclopædia Britannica, making a big impression on him. It was here his interest in all things relating to energy really took off, to the point where he would perform his own experiments to prove what he had read.

Faraday’s life was to be set on its ultimate path when a customer to the book shop, William Dance, offered the young Faraday tickets to attend a series of lectures at the Royal Institution by the eminent scientist Humphry Davy.

2. Early Career at the Royal Institution

Ever the willing student Faraday took copious notes from the Davy lectures, which he turned in to a 300 page book.

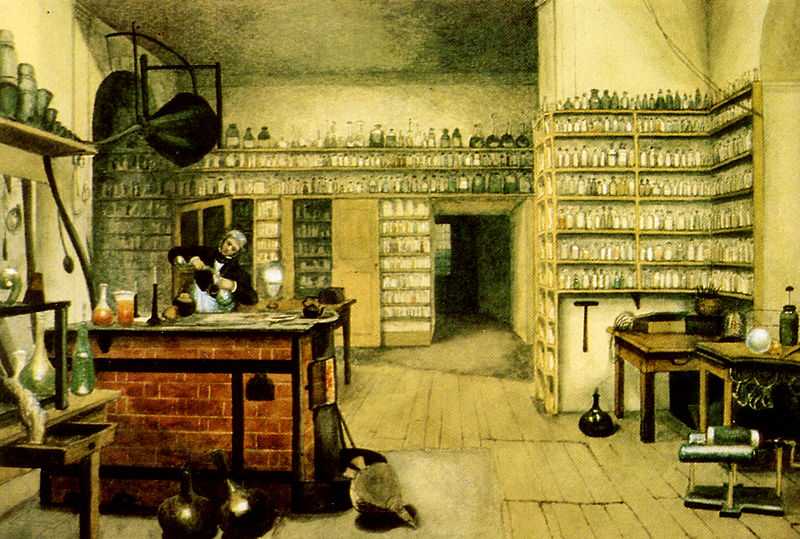

Using his professional experience to date he bound the book and sent it to the great man himself. Davy must have been duly impressed with what he saw and was soon to offer Faraday a job as his assistant. On March 1st 1813 Faraday began his first day of work at the Royal Institution.

Initially he was a chemical assistant before acting as Davy’s secretary on an 18 month tour of Europe, where he met some of the continent’s finest scientists. Back in London Faraday’s name was rising and in 1816 he gave his first lecture and published his first academic paper.

By the time his apprenticeship with Davy came to an end in 1820, Faraday had built up a knowledge of chemistry and chemical analyses which was second to none.

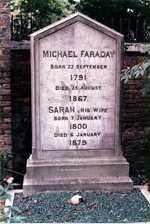

1821 proved to be a highly significant year for Faraday, now aged 29. In June of that year he married Sarah Barnard who he had met through their respective families at the Sandemanian church they attended and they settled permanently in to rooms at the Royal Institution.

The same year also saw Faraday begin work on the research in to electricity and electromagnetism which still impacts us all to this day.

3. Electromagnetic Rotation and Induction

In 1820 the Danish physicist and chemist, Hans Christian Ørsted, announced how he had discovered the flow of electricity through a wire created a magnetic force around the wire.

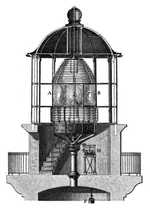

Faraday’s brilliance was taking the notion that this magnetic force could be circular and building two devices to produce a continuous circular motion which he termed electromagnetic rotation. This was the beginnings of what would eventually develop in to the electric motor.

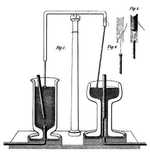

The next 10 years saw Faraday carry out a series of experiments which would result in his groundbreaking discovery in 1831 of electromagnetic induction, generating electricity in a wire through the electromagnetic effect of a current in another wire.

Through his work in1831 Faraday showed you could create a steady electric current through rotation or kinetic energy, a principle which remains crucial today with many homes powered this way.

Following this great discovery Faraday continued to research electricity, including a series of experiments in 1832 looking at the fundamental nature of electricity. Faraday was hoping to prove that all types of electricity had the same properties and caused the same effects.

This work led to the creation of a new field, electrochemistry, with Faraday’s observations still relevant today and the basis for modern technologies, such as batteries for mobile technology.

4. His Later Life

A decade of devoted research had started to take a toll on Faraday’s health and he withdrew from his work for a few years.

On his return in 1845 he introduced the term diamagnetism following his discovery that substances can show a weak repulsion to a magnetic force. The same year Faraday returned to a topic which had always interested him and which he had worked on following his discovery of electromagnetic rotation in 1821. In what is known as the Faraday Effect he became the first to link electromagnetism and light, with a magnetic field causing rotation in the plane of light polarisation.

Faraday was to carry on with occasional experiments and he was also a frequent lecturer at the Royal Institution. As a reward for his scientific service he was given the use of a house at Hampton Court by Queen Victoria, although he turned down the accompanying knighthood also offered, preferring to remain Mr Michael Faraday. Sadly by 1855 this great mind was starting to fail Faraday and in 1858 he retired to his new home, 45 years after that first day at work in the Royal Institution.

Throughout his life he was devout to his faith, serving as a deacon and elder in the Sandemanian church. His faith may have played a role in declining an offer by the British Government to help develop chemical weapons during the time of the Crimean War. Faraday was also interested in fields of science beyond his own and had a strong interest in the natural world.

In 1865 he helped produce a report with Charles Lyall about the dangers of coal dust following an explosion at a mine in County Durham, as well as studying the effects of pollution in London and the river Thames.

5. Faraday’s Legacy

Most people might aspire to just one of the achievements of Faraday in their lifetime.

Even in his early years at the Royal Institution he designed a forerunner for the Bunsen burner still used in classrooms and labs across the world.

Not content with that he identified the substance Benzene in 1825, an important chemical which is used in the production of plastics. His observations on conductors also led to the Faraday Cage which offers protection to sensitive electronic equipment by blocking electromagnetic fields. The list of scientific discoveries and inventions for one man is quite remarkable.

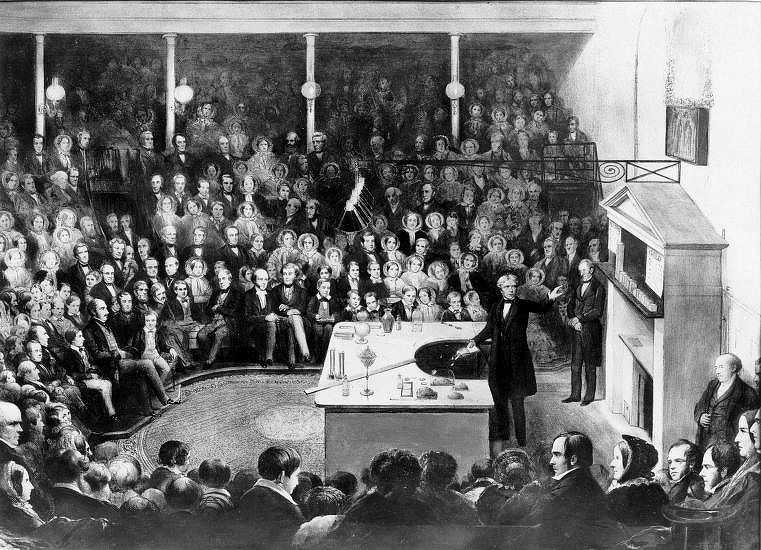

He also introduced the terms anode, cathode and electrolyte in relations to batteries. To commemorate his scientific achievements the Bank of England featured an image of Faraday lecturing at the Royal Institution on the back of £20 notes from 1991 through to 2001.

Faraday was twice offered the Presidency of the Royal Society but turned it down on each occasion. His influence on the world of chemistry and science was acknowledged by other great scientists including Albert Einstein who kept a photo of Faraday on his wall, hanging next to the likes of Isaac Newton.

Ernest Rutherford was another who praised Faraday to the hilt in his quote,

"When we consider the magnitude and extent of his discoveries and their influence on the progress of science and of industry, there is no honour too great to pay to the memory of Faraday, one of the greatest scientific discoverers of all time."

Michael Faraday died on August 25th 1867 at his Hampton Court house, survived by his wife Sarah. They never had children. He was buried at Highgate Cemetery in North London having in his lifetime been offered the chance of a burial at Westminster Abbey. Like the Knighthood before he turned the offer down, though a plaque in the Abbey marks this pioneering scientist. His wife Sarah would also be buried with him at Highgate.

A fitting statue of Faraday sits in Savoy Place in London, outside the Institution of Technology and Engineering. In 2017 the Faraday Institution was set up as an independent institute centred on electrochemical energy storage research. Its aim as part of the Faraday battery challenge is to make the UK a leader in developing new electrical storage solutions, ensuring the name of Faraday remains at the forefront of the day’s cutting edge scientific research and development.