1. William and Mary's early life

William III (baptized William Henry) was born on November 4, 1650 in Binnenhof Palace, The Hague, Netherlands. On January 21, 1651, he was christened at the Grote Kerk in Haarlem.

William was the only child of stadtholder William II, Prince of Orange, and Mary, Princess Royal. Eight days before he was born, his father died of smallpox. William became the sovereign Prince of Orange from the moment of birth.

From April 1656, William received daily instruction in the Reformed religion from the Calvinist preacher, Cornelius Trigland.

From early 1659, although he was never officially enrolled, William spent seven years at the University of Leiden for a formal education under the guidance of ethics professor Hendrik Bornius. Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt and his uncle Cornelis de Graeff pushed the States of Holland to take charge of William’s education. The States acted on September 25, 1660.

On December 23, 1660, William’s mother died of smallpox. In her will she requested that her brother, King Charles II of England, look after William. On September 30, 1661, the States of Holland relinquished control.

After the Second Anglo-Dutch War, one of King Charles II’s peace stipulations was the improvement of William’s condition. In 1666, as a countermeasure, William was made a ward of the state. DeWitt, the leading politician, took charge of William’s education and instructed him weekly in state matters.

Mary II

Mary was born on April 30, 1662 at St. James’s Palace in London. She was the eldest daughter of the Duke of York (future King James II) and his first wife, Anne Hyde. Mary was baptized into the Anglican faith in the Chapel Royal at St. James and was named after her ancestor, Mary, Queen of Scots.

In 1660 Prince Charles Stuart, who had been in exile, returned to London and was crowned King Charles II. He was Mary’s uncle. His return was referred to as the Restoration.

Charles II’s court was notorious for its immorality. Women were often regarded as ornaments or playthings. Mary learned nothing of history, geography, or law. Her knowledge of English spelling and grammar was rudimentary.

For the most part, she received her education from private tutors and was largely restricted to music, dance, French, and a good grounding in the Protestant religion. She could both speak and write French competently. Also, she took drawing lessons from Richard Gibson, a professional painter of miniatures.

2. Their early career

William’s father had been stadtholder of five of the United Provinces of the Netherlands. When he died it left the office of stadtholder vacant in several provinces.

A powerful republican oligarchy dominated the province of Holland and the city of Amsterdam and wanted to exclude the house of Orange from power.

In 1668, the Orangist Party attempted to bring William to power and proclaim him Stadtholder and Captain General. The Act of Seclusion in 1654, prompted by Oliver Cromwell, which barred the Prince of Orange and his descendants from office in the state, had been rescinded with the return of Charles II, but there was still opposition. Ironically, de Witt was among those who thought the two positions gave William too much power.

In March 1672, Charles II and Louis XIV declared war. William had been given limited authority. The Dutch navy kept the English in check, but the army had been neglected. William and his few troops were left to defend the waterline. They flooded the low-lying areas which was deep enough to make an advance on foot precarious and shallow enough to rule out effective use of boats.

In 1672, various attempts were made to destroy the Dutch Republic. The Franco-Dutch War and the Third Anglo-Dutch War were all efforts made by France, England, Munster, and Cologne. It was called The Disaster Year.

On July 4, 1672, William was appointed Stadtholder and Captain General of the Dutch forces to resist French invasion of the Netherlands.

3. Rise to Power

William saw the need to repair relations between England and the Netherlands following the Anglo-Dutch Wars.

To accomplish this, he turned his attention to marriage, particularly with his cousin, Mary, niece of King Charles II.

Marriages, especially for women, were arranged. They considered themselves fortunate if their intended spouse was wealthy, smart, and physically attractive. It was a ‘crapshoot,’ in some cases, and a woman had to be grateful if her intended spouse had one out of the three desired attributes.

Not love at first sight

Mary didn’t like the proposed agreement and was disappointed when she met William.

The office of Stadtholder was impressive, but he wasn’t wealthy and he wasn’t physically attractive. He was twenty-seven, twelve years her senior, and a plain man; hooked nose, fragile physique, asthmatic cough. Although, she was an impressionable fifteen-year-old, she was a striking brunette, slender, graceful, and ‘tall.’ She was four inches taller than William.

William did not want an elaborate wedding. They were married on November 4, 1677. It was a small, private affair, held in Mary’s bedchamber at St. James’s Palace with only the closest relatives present. Mary cried throughout the ceremony while William maintained a somber expression. Henry Compton, the Bishop of London, officiated.

Two weeks later, William took his bride back to the Netherlands. Although William viewed the wedding as a symbolic union of the English and Dutch and hoped it would provide resistance to French ambitions, King Louis XIV was still a threat. He knew he had to actively work toward building a coalition of European states alarmed by Louis’s aspirations.

During William’s military campaigns, Mary ruled in her own name, proving herself to be a powerful, firm, and effective ruler.

Getting rid of James

King Charles II died on February 6, 1685. He’d had a cavorting lifestyle and frequently feuded with Parliament. His brother James ascended to the throne and ruled from 1685-1688. His ruling style was just as contentious as his brother’s and he openly flaunted his Catholicism.

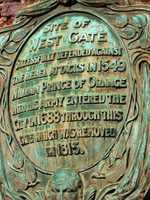

After receiving a request from influential English Protestants, William landed at Torbay on November 5, 1688. He had 463 ships unopposed by the Royal Navy. His army of 14,000 troops gathered local support and increased to over 20,000.

His advance on London became known as the Glorious Revolution.

James fled to France and abdicated his throne. Mary was invited to take the throne, but she didn’t want to rule alone. She felt her husband should be crowned. A compromise was reached and on April 11, 1689, in Westminster Abbey, William and Mary were crowned King William III and Queen Mary II by Henry Compton, Bishop of London.

As a part of the ceremony the new king and queen were required to adhere to the Coronation Oath Act, passed by Parliament in 1689 as well as The Bill of Rights, a landmark Act in the constitutional law of England. In general, both pieces of legislation laid down the limits on the powers of the monarch, set out the rights of Parliament, and clarified who would be next to inherit the Crown.

In 1690 at the Battle of the Boyne in Ireland, the newly crowned King William III defeated the Catholic army, including troops from France and Ireland, led by the deposed James II who sought to regain the Crown.

4. William and Mary's legacy

William III remains most noted for having fought France, the dominant power in Europe.

For over thirty years, including The Nine Years War from 1688 to 1697, he and a coalition comprised of the Holy Roman Empire, Dutch Republic, Spain, England, and Savoy held back the tide of French domination.

Mary II made it possible for her Dutch husband to become co-ruler of England after he overthrew James’s government. She rejected proposals that she become sole ruler to the exclusion of her husband.

In addition to popularising blue and white porcelain, and influencing landscape gardening, a charter was signed on February 8, 1693 for the establishment of a college in the Virginia Colony in America which, today, is The College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Mary died on December 28, 1694 of smallpox. William ruled alone for eight years until his death on March 8, 1702. He died of pneumonia.

William and Mary are buried in Westminster Abbey.