1. Turing's early life

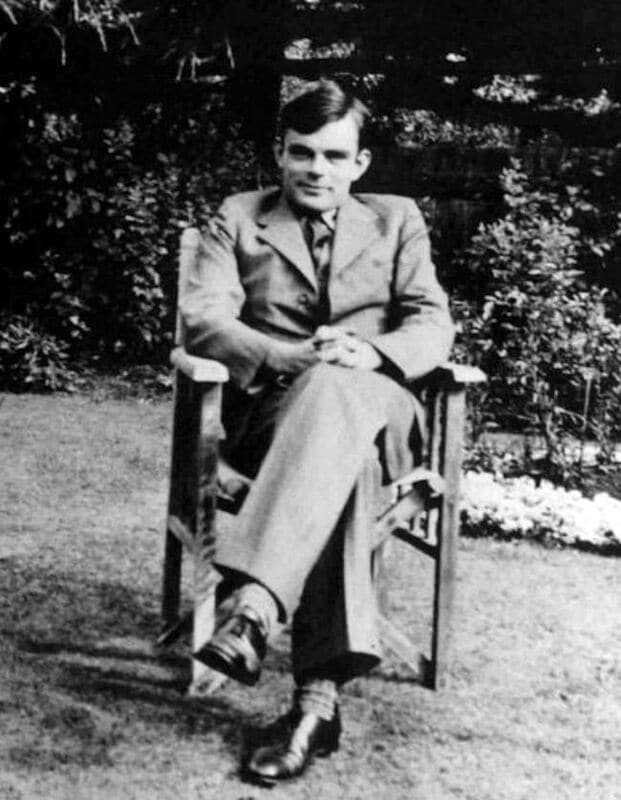

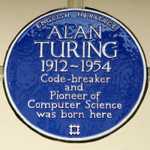

Alan Mathison Turing was born on June 23, 1912 at Warrington Lodge, Maida Vale, London.

He was the second son of Julius Mathison Turing, an Indian civil servant (ICS) working in Chatrapur, India and Ethel Sara Stoney. Alan’s parents lived in India while he and his brother John lived in various foster homes.

Alan was a toddler when he and his brother John were left with a retired Army couple, Colonel and Mrs. Ward, who lived in a large house called Baston Lodge in St. Leonards-on-Sea. The Wards had four daughters of their own, boarded another boy, and at one point took in three of Alan’s cousins.

In 1916, when Alan was four, his mother returned from India. She rented some rooms in St. Leonards and remained there for the next three years.

In 1917, Alan’s brother was sent to a preparatory school called Hazelhurst near Tunbridge Wells in Kent. Alan was left with his mother who busied herself with church and watercolor painting. Alan taught himself to read from a book called Reading Without Tears. He was good at recognizing figures and developed a habit of stopping at every lamp post to read its serial number.

In the summer of 1918 Alan was enrolled at St. Michaels, a private day school in St. Leonards. He remained there until the age of ten and then joined his brother at Hazelhurst.

When Alan was eleven, his mother left him and his brother with a new foster parent, Archdeacon Rollo Meyers in Hertfordshire. A short time later, Alan’s father resigned from Indian Civil Service and he and his brother moved with their parents to Dinard, France.

At the age of fourteen, Alan was enrolled at Sherbourne School, an independent boarding school in the town of Sherbourne in Dorset. The first day of school coincided with the 1926 coal miners’ strike. All transportation except the milk trains was halted.

Alan was adventurous and left Dinard on May 2, 1926 and took a ferry from St. Malo to Southampton. From there, he rode his bicycle sixty miles for the better part of two days to Sherbourne, resting overnight at an inn. He arrived on time for the first day on May 3. His five-year tenure was intellectually stimulating, but emotionally bittersweet.

2. His early career

From 1931 to 1934, Alan attended Kings College, Cambridge. Christopher Morcom, his best friend at Sherbourne, had died. With no one to share his intellectual curiosity, he turned to pure mathematics to cope with his grief.

Other than the rowing club, Alan was basically a ‘loner.’ He joined the Moral Science Club and in 1933 was asked to read a paper. The crux of his paper, Mathematics and Logic, was that a purely logistic view of mathematics was inadequate; and that mathematical propositions possessed a variety of interpretations, of which the logistic was merely one.

In 1934, Alan graduated from Kings College. His dissertation was called the Central Limit Theorem. It was a key concept in probability theory because it implied that probabilistic and statistical methods that worked for normal distribution (informally a bell curve) could be applicable to many problems involving other types of distribution.

Alan had neglected to check to see if his objective had already been obtained. As it turned out, his work had already been proven by Jarl Waldemar Lindeberg in 1922. Alan was told that his work might still be accepted as original work for a King’s Fellowship, provided he did more work on it. In the spring of 1935 Alan was elected a Fellow at Kings College.

Alan had been intrigued by David Hilbert’s Entscheidungsproblem (decision problem) and the questions it raised. In the summer of 1935, he began to dream of creating a machine that could manipulate symbols and decide the probability of any math assertion presented to it without the interference of human judgment, imagination, or intelligence.

By simulating the work done by any machine, it would be ‘universal.’ Further, anything performed by a human computer could be done by his machine and perform the equivalent of the human mental activity. In short, this machine would be an ‘electric’ brain.

Alan began to compile his notes on what he called the Universal Turing Machine into a possible paper for publication. He learned Alonzo Church, an American mathematician and logician, had also been studying the work of Hilbert.

Alan’s paper, On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, was published on May 28, 1936 in the Proceedings, London Mathematical Society.

Alan realized that the United States was an important place for advanced research and applied for a Visiting Fellowship at Princeton University, a research university in Princeton, New Jersey. In the fall of 1936, he entered Princeton University where he studied under Alonzo Church. It was Alan’s hope that after a year at Princeton he could get reelected to another fellowship at Cambridge.

When the fellowship didn’t materialize, he decided to stay another year at Princeton and work on a Ph.D. He turned toward Kurt Godel’s work and delved deeper into his theorems of mathematical logic that demonstrated the inherent limits of every formal axiomatic system capable of making basic arithmetic. Alan completed his Ph.D. requirements in 1938 and returned to Cambridge.

3. Turing's works

On September 4, 1939, the day after the United Kingdom (UK) declared war on Germany, Alan was asked to come and work as one of the cryptanalysts at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&GS) in Bletchley Park.

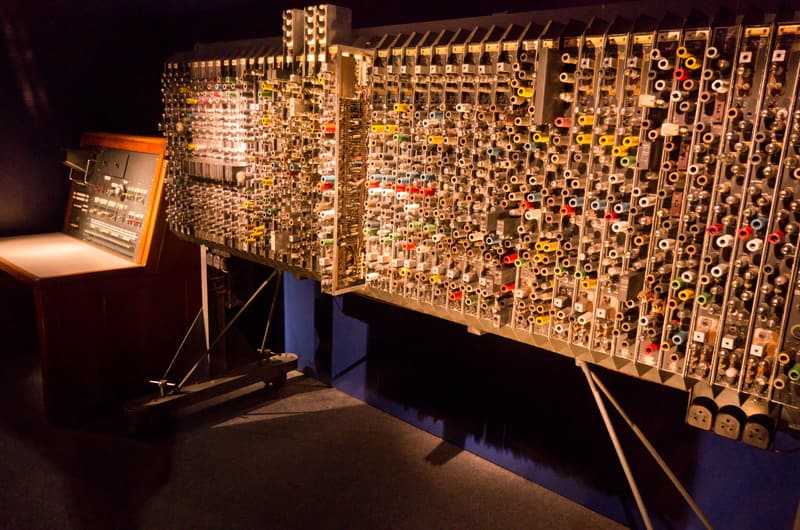

It was Britain’s code breaking center that adopted Ultra, a designation for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high level enemy radio and teleprinter communications. Alan’s mission was to ‘crack the code’ for Nazi Germany’s upgraded version of Enigma. Britain was familiar with the details of the Enigma machine’s rotors and the method of decrypting Enigma machine messages. The Polish government, who had briefed them, had also invented the Bomba, a code breaking machine, but the Germans changed its operating procedures which made the Bomba useless.

Alan invented a machine and called it the Bombe. It was an electromechanical machine comprised of the equivalent of thirty-six different Enigma machines, each containing the exact internal wiring of the German counterpart. This machine helped to reduce the work of the code breakers.

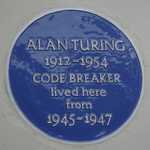

Alan invented the Turingery which was the first systematic method for cracking Germany’s Tunny, a German cipher machine teleprinter communications network (much like a mobile phone). After the war, from 1945 until his death in 1954, Alan worked on a series of projects. At the National Physical Laboratory, he designed the Automatic Computing Engine. It was one of the first designs for a stored-program computer. He became Deputy Director of the Computing Machine Laboratory at the Victoria University of Manchester where he worked on software for one of the earliest stored program computers – the Manchester Mark I.

In 1952, Alan turned his attention to mathematical biology and published a paper called The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis, which discussed the development of patterns and shapes in biological organisms.

Later, in that same year, Alan was charged with ‘gross indecency’ under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885. He was ordered to undergo treatments designed to reduce the libido. For over a year, he was injected with synthetic oestrogen. In 1954, his housekeeper found him dead in his bed. The death was ruled a suicide by cyanide poisoning.

4. The legacy

Alan Mathison Turing had an I.Q. of 185: top 0.1% of the population of the world. He was always unwilling to be intellectually compromised.

Alan defined himself as an ‘ordinary English homosexual atheist mathematician.’ However, in 1952, an indiscretion led to his arrest in the United Kingdom.

An apology to Alan was issued by Prime Minister Gordon Brown in 2009 and Queen Elizabeth issued an official pardon in 2013. These efforts led to the Alan Turing Law which struck a chord for tolerance of diversity, in general, and the treatment of Alan Turing, in particular.

Alan Mathison Turing died on June 7, 1954. His remains were cremated at Woking Crematorium on June 12, 1954 and his ashes were scattered in the gardens of the crematorium.

Alan Mathison Turing might have been many things, but he was not ‘ordinary.’