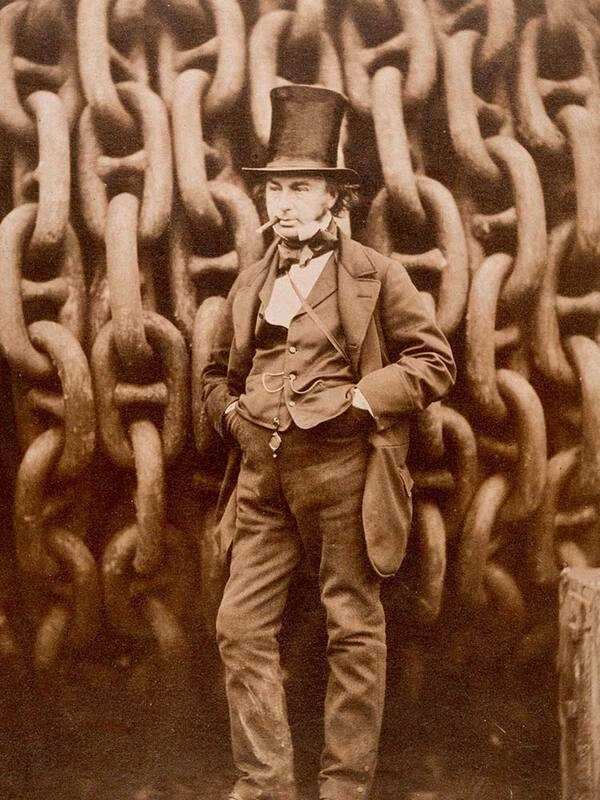

1. Brunel's Life

Born on 9 April 1806, Isambard Kingdom Brunel was the third and final child of Marc Isambard and Sophia Kingdom Brunel.

Marc was an able inventor, at the time working for the Royal Navy. Brunel started his career as an apprentice to a watchmaker in France, his parents having been sent to debtors’ prison, before returning to London to work in his father’s engineering office at the age of 16.

The Thames Tunnel

He was thrust immediately into one of the most ambitious projects of the age: building the Thames Tunnel between Wapping and Rotherhithe.

The project required tunnelling through soft earth using a tunnelling shield designed by Brunel’s father. But many workers still lost their lives, with Brunel involved in a serious accident in January 1828. Construction was not finally completed in 1848.

Bridges, Railways and Ships

When Brunel branched out on his own, he devoted himself to three main things: bridges, railways and ships. His most famous bridge is the Clifton Suspension Bridge over the River Avon, at the time the world’s longest suspension bridge; Brunel won the design competition for this bridge in 1831.

Brunel was then appointed Chief Engineer of the Great Western Railway and many smaller railway companies up and down the land. The Great Western is world-famous for its architecture, in particular the Paddington and Bristol Temple Meads stations, the Hanwell and Chippenham viaducts, the Maidenhead Bridge and Box Tunnel.

Brunel also designed three steamships, each bigger than the last: the Great Western (which steamed to America in 12 ½ days); the Great Britain (the first iron ship with screw propellers); and the Great Eastern (the largest ship of its time, but which proved impractical and was eventually scrapped).

Brunel’s other endeavours included designing a field hospital for use in the Crimean war, designing dockyards, and the design of a novel but commercially unsuccessful atmospheric railway.

Personal life

Brunel was married with three children. But he was a workaholic whose health failed as a result of stress. He suffered a stroke after the launch of the Great Eastern in September 1859 and died a week later at the age of 53.

Brunel died too young to be knighted by Queen Victoria, something his father achieved in 1841 for work on the Thames Tunnel.

In his time, Brunel was seen as a brilliant, creative and unreliable engineer who was not the equal of Robert Stevenson (who is most famous for the Rocket locomotive and his work on the Stockton and Darlington Railway). Posterity has judged Brunel more kindly, with a university even being named after him.

2. Railways

In the early 19th century, the building of railways was in its infancy.

There were many technical challenges: blasting through rock, building lengthy bridges and optimising track design to name but a few. Brunel met all of these challenges but also wanted his designs to be stylish. After all, train travel was the new mode of transport.

The GWR

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was surveyed by Brunel between 1833 and 1834, with the Act of Parliament authorising its construction passed in 1835. The 118-mile long route from London to Bristol, via Reading and Bath, posed a number of challenges.

Chief amongst them was the crossing of the narrowest point of the River Tamar at Saltash, a span of 1,100 feet, which had to be achieved whilst allowing enough height for ships to pass underneath. Brunel’s solution was to design what became the Royal Albert railway bridge.

Box Hill

Another difficulty came in the form of Box Hill, found between Bath and Chippenham, which Brunel overcame by designing the 2-mile long Box Tunnel, the construction of which consumed one tonne of explosives per week and required the excavation of about 200,000 cubic metres of soil.

The legend that the sun shines all the way through the tunnel on Brunel's birthday each year is, unfortunately, untrue!

Broad gauge

Brunel’s relations with the GWR’s board of directors were not harmonious. He insisted on using broad-gauge track, that is a track that was 7 ft 1/4 inch wide, as opposed to the standard 4 ft 8 1/2 inches.

Brunel argued that his wider guage was the best size for speed, comfort and transporting goods. But the idea meant that new locomotives and carriages for the GWR had to be designed.

Broad gauge was eventually abandoned, years after Brunel's death, at great expense.

Station designs

In addition, several of Brunel's designs were rejected on the basis that they were overly ornate and therefore costly. The GWR was, after all, a private company and the investors that Brunel charmed into parting with their money wanted to see a return.

Some of Brunel's designs managed to slip through, though usually only in modified form. The grandest remaining terminus is London’s Paddington station, the roof of which is supported by three huge wrought-iron arches spanning 68, 102 and 70 feet respectively (a fourth span was added in 1915).

Of Paddington, Brunel observed:

"I am going to design, in a great hurry, and I believe to build a station after my own fancy; that is, with engineering roofs, etc. etc. It is at Paddington ...."

Dodgy engines ...

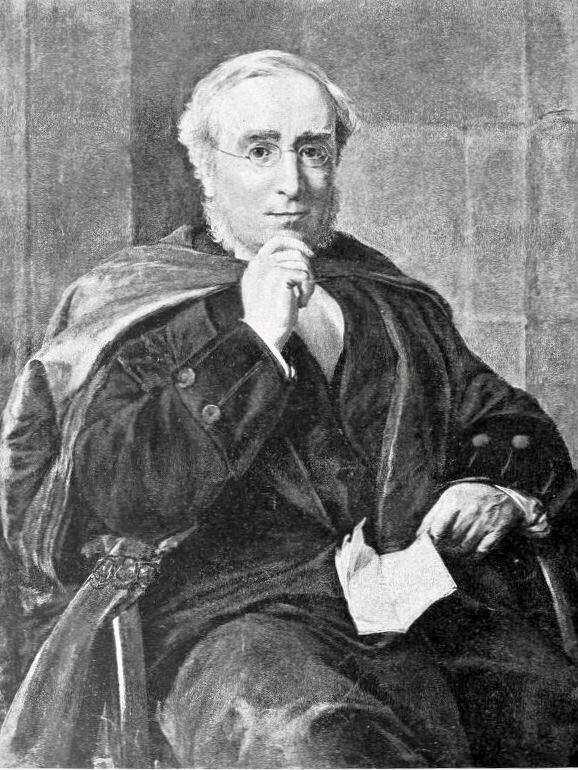

Another problem was that the initial batch of steam engines ordered by Brunel, and modified to his design, weren't fit for purpose. Brunel, realising that he was not a great mechanical engineer, called in the 20-year old Daniel Gooch. Gooch, who had previously worked for Robert Stephenson, got the engines working and thereafter set about revolutionising engine design. He later became a politician and Baronet.

3. Bridges

The Clifton Suspension Bridge, Brunel’s most famous structure, is a 210-metre suspension bridge some 60 metres above the Avon Gorge.

It had, at the time of its construction, the longest span of any bridge in the world. The bridge is still standing and is used by over 4 million vehicles annually.

Brunel’s other bridges include the Royal Albert Bridge over the River Tamar (described above), the Windsor Railway Bridge (the oldest wrought-iron bridge still in service today, of bow and string design and spanning 62 metres), the Maidenhead Railway Bridge (which spanned the Thames and was the widest brick arch bridge ever built) and the Hungerford Bridge near Charing Cross station.

4. Ships

Brunel had a great vision: that passengers could board a train in London, change onto a steamer at Bristol, and be whisked to New York.

The Great Western Steamship company was formed by Thomas Guppy to turn this into reality.

Great Western

Brunel’s first ship was the 72-metre long SS Great Western, at the time the longest ship in the world. Brunel’s calculations suggested that a larger vessel would be able to carry enough fuel to power steam engines for the entirety of an Atlantic crossing. He was proved correct, with the Great Western arriving in New York on her maiden voyage in April 1838.

The Great Western also won the Blue Riband, an accolade given to the fastest passenger liner crossing the Atlantic (its average speed was 8.66 knots or 16.04 km/h). In total it made 64 crossings.

Great Britain

Brunel had therefore proved that a commercial trans-Atlantic steamship service was a viable proposition. His next ship, the Great Britain, used a propeller instead of paddle wheels for increased efficiency. It is generally considered the first modern ship, being built of metal, engine-powered and driven by propeller.

Though the Great Britain ran aground shortly after her first voyage, she was later used in voyages to Australia, and is fully preserved in Bristol.

Great Eastern

Brunel’s final ship, the Great Eastern, was intended for longer voyages to India and Australia. Over 200 metres long, she was powered by propeller and paddle wheel and fitted with luxurious apartments capable of accommodating up to 4,000 in style.

Though the ship overcame numerous practical and engineering challenges, she was not a commercial success (laying transatlantic telegraph cable rather than carrying passengers, and eventually scrapped).