1. Early life

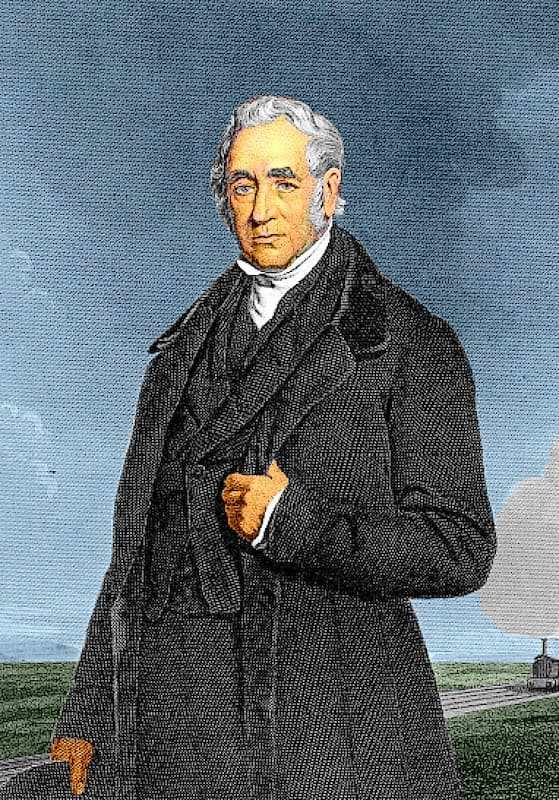

George Stephenson was born on June 9, 1781 in Wylam, Northumberland. He was the second of six children to Robert, a fireman at Wylam Colliery, and his wife, Mabel.

George

At age ten, George drove horses that carried the coal carriages. At age seventeen, he became an engineman at Water Row Pit in Newburn. He studied at night school to learn reading, writing, and arithmetic. He was illiterate until age eighteen.

Robert

Robert Stephenson was born on October 16, 1803 in Wellington Quay, Northumberland. He was one of two children born to George, a brakeman, and his wife, Frances Henderson. Robert was sent to the village school in Long Benton. At the age of twelve, his father enrolled him in Percy Street Academy in Newcastle, a private school for the children of middle-class parents.

At the age of fifteen, Robert was apprenticed to Nicholas Wood, a mining engineer, for three years.

When Robert was nineteen, he spent six months at Edinburgh University. He studied natural philosophy, chemistry, and natural history.

2. Early career

In 1801, George became a brakeman for Black Callerton Colliery and the next year, 1802, he married Frances Henderson and moved to Wellington Quay.

George

In 1803, Frances gave birth to Robert. A daughter, Frances, followed in 1805, but she died three weeks after birth. Frances’s death followed in 1806.

George was promoted to engine-wright in High Pit, Killingworth, where he became an expert in steam driven machinery. George’s unmarried sister, Eleanor, took care of Robert. In 1806, 1809, and 1812, several blasts at two collieries, West Moor and Brandlings’ Felling Pit, killed over a hundred men. It was a lighting problem.

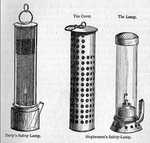

George believed that he could solve the problem. Several safety lamp designs were tried. Sir Humphry Davy, a foremost scientist, offered his suggestion. He conducted his experiments in the laboratory of the Royal Institute.

George conducted experiments by traveling through a pit at Killingworth at the risk of his life. Unbeknownst to each other, George and Sir Humphrey designed similar lamps.

George’s lamp proved to be more successful. Sir Humphrey announced the successful outcome of his experiments to the Royal Society in a scientific paper, On the Fire-Damp of Coal Mines and on Methods of lighting the Mine so as to prevent its explosion. Sir Humphrey’s scientific colleagues praised him and he was awarded the sum of 2,000 pounds for his invention. George’s work was discounted as the clumsy efforts of an uneducated man. He was given a hundred guineas.

George’s supporters were angered and attested to the fact that George’s lamp was the first in practical use. At a special ceremony, George was given 1,000 pounds. The lamp became the standard for gaseous pits. George’s name was cleared, but he never forgave Sir Humphrey.

Robert

After being released from his apprenticeship to Henry Wood, Robert joined his father and helped him survey the Stockton and Darlington Railway. His father had built a locomotive called the Blucher and had gained a modicum of respect in the field. Traveling to Darlington with his father marked the beginning of his railway engineer career.

Robert’s father decided to form his own company. Robert was invited to invest in the company, along with Edward Pease and Michael Longridge. The company was named Robert Stephenson and Company, Forth Street Works, Newcastle. Robert was made Managing Partner and paid 200 pounds per year.

3. Finest works

In 1813, George supervised the construction of a locomotive for the Killingworth wagonway in the West Moor Colliery workshops. Blucher was created.

George

The building of the Blucher brought George’s name to the attention of some influential men on Tyneside. Among them was William Losh, a partner in an ironworks industry and one of the men who supported him in the safety-lamp controversy.

On March 29, 1820, George married Betty Hindmarsh. He had fallen in love with Betty when they were teenagers. Her father wouldn’t agree to their marriage, because George was poor. She vowed she’d never marry anyone else. She was true to her word.

George consulted for the Hetton Railway. He designed the first railway to use no animal power. Gravity was used for downward inclines and locomotives for level and upward stretches.

An invention by John Birkinshaw which perfected wrought iron rails caught George’s attention. His enthusiasm for its possibilities caused a rift between he and Losh. However, Birkinshaw’s firm was not equipped to construct the locomotives and engines of George’s design.

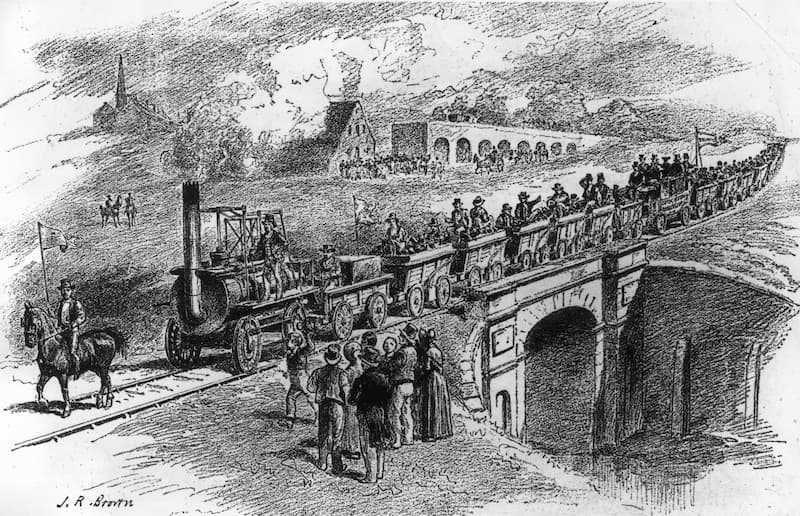

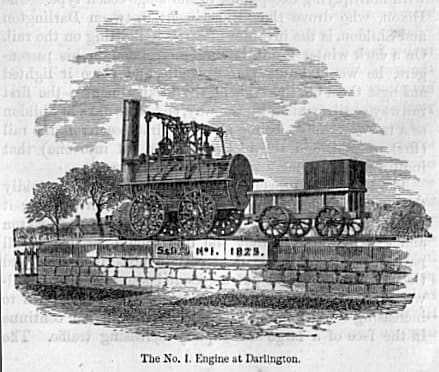

George believed that the demand for locomotives would increase as railways spread. This led him to form his own company. His company, Robert Stephenson and Company received orders for four locomotives. They were named Locomotion, Hope, Black Diamond, Diligence, Experiment. The latter was the first purpose-built passenger car. In September 1825, the Stockton and Darlington Railway made its successful launch.

Later, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was proposed. The directors of the company initiated a competition called the Rainhill Trials for interested engineers. There was a parade and several dignitaries attended, including the Duke of Wellington who was the Prime Minister.

In the parade George, his son, his brother, Robert, and John Locke each drove a locomotive. They were called the Northumbrian, Phoenix, North Star, and Rocket. Robert was responsible for the detailed drawing of Rocket which won.

In 1830, George designed a ‘skew bridge’ over the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. This was the first bridge to cover any railway.

In that same year, he invested 2,000 pounds in the Leicester and Swannington Railway. He moved to Alton Range and bought Snibston estate. There he discovered a coal mine, which became very lucrative.

The years 1845 to 1848 were bittersweet years for George. In 1845, his wife, Betty, died. In 1847, he was installed as the first president of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. In 1848, he married Ellen Gregory. The marriage, however, was short.

On August 12, 1848, George died at Tapton House in Chesterfield, Derbyshire. He was buried at Holy Trinity Church, Chesterfield.

Robert

After an unproductive three-year stay in Columbia, South America as a mining engineer, Robert came home and took responsibility for the Canterbury and Whitstable Railway. His father was occupied with the Liverpool and Manchester job.

In 1828, there had been growing interest in favor of haulage, not by horses, but by fixed haulage engines and not locomotive haulage. His father’s untiring advocacy for the locomotive was unsuccessful. Robert with the aid of John Locke prepared a winning report which elaborated on his father’s earlier report. It was titled Observations on the Comparative Merits of Locomotives and Fixed Engines.

In 1829, Robert married Fanny Sanderson and settled in Greenfield Place, Newcastle. In the 1830s Robert had an opportunity to travel with his father and alone to Europe on consulting jobs. His foreign travel experience was impressive and he was sought after by businessmen and Parliament.

On October 4, 1842, his wife, Fanny died. After her death, Robert attempted new ventures. He built an iron bridge to cross the River Dee and the Britannia Bridge to cross the Menai Straits from Wales to the Island of Anglesey. He also became a member of Parliament (MP), representing Whitby.

Robert died on October 12, 1859. He was buried in Westminster Abbey.

4. Their legacy

George led the world in the development of railways.

George

The Stockton and Darlington Railway and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway were projects that paved the way for railway engineers. George believed railways would eventually join together. The global standard guage, 4’ x 8 ½”, is credited to him.

Robert

Robert was a pioneer. He helped to create a new mobility for villages, small towns, townships, and cities. When Robert died, his company, Robert Stephenson and Company had some 1500 employees.

He made generous donations to the Newcastle Locomotive Works and Snibston Collieries (400,000 pounds), the Parker, Bidder, Newcastle Infirmary (10,000 pounds), and the North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers (2,000 pounds). He also left 50,000 pounds to his cousin, George Robert Stephenson.