1. Alfred's early life

Alfred was born in AD 849 in the royal estate in Wantage, Bershire.

He was the youngest of five sons of King Ethelwuf of Wessex and his first wife, Osburh.

In AD 853, at the age of four, Alfred was sent on a lengthy pilgrimage to Rome. Despite his youth and the fact that he was fifth in line from the throne, his father hoped the appearance of his young son in Rome would win the favor of Pope Leo IV for the king and his nation. When Alfred returned to Wessex in AD 854, he discovered that his oldest brother, Ethelstan, and his mother had died.

Alfred was more than twenty years younger than Ethelstan and rarely interacted. The death of his mother, however, devastated him. She had given him a little book of poetry. He couldn’t read the book himself, but he learned poetry by hearing it recited and then repeating it.

The deaths caused Alfred’s father to do some serious soul searching. He decided to make a pilgrimage to Rome. Before leaving, he appointed Ethelbald, now the oldest son, acting king of Wessex in his absence. Ethelberht, the second oldest, would serve as subking of four regions: Kent, Surrey, Sussex, and Essex, and Alfred would return with him to Rome.

While in Rome, Alfred’s father decided to marry Judith, the twelve-year-old daughter of Charles the Bald in Verberie-sur-Oise, allying Wessex with the most powerful family on the continent. However, Charles would only agree to the marriage if his daughter was to be received as Ethelwuf’s wife and queen of Wessex. Ethelwuf was hesitant.

A former king of Wessex had been mistakenly poisoned by his wife. One of his advisors was the intended victim. She had been driven out of the kingdom, but her actions spooked later kings of Wessex. Nevertheless, Charles insisted and Ethelwuf, desperate for the political alliance, agreed.

In January AD 858, Alfred’s father died and his brother, Ethelbald became the king of Wessex. He wasn’t satisfied with just the throne, he decided to marry his stepmother, Judith. He thought it would bring all the Carolingian legitimacy that his father had received. Instead, he invoked disgust and lack of respect from his subjects.

His reign would have been endangered if not for a disease that he contracted. He died shortly after the marriage and Judith returned to her father. In AD 860, Ethelberht, the next son in line, took the throne. His reign was short. By AD 865, he was dead and the fourth son, Ethelred, became king with Alfred next in line.

2. Early career

In AD 867, a Viking army attacked Nottingham, the capital of the kingdom of Mercia.

The Mercian king, Burgred, appealed to Wessex for aid. He had married Ethelred’s and Alfred’s sister, Ethelswith, in 853 AD, to forge a military alliance between the two kingdoms.

The Vikings retreated behind the city walls of Nottingham and refused to come out and fight. Ethelred’s forces were not prepared to break through Nottingham’s ramparts and city walls and Burgred realized that he would not be able to wait the Vikings out. He won the peace by bribing the raiding army to leave.

Alfred was disappointed, but shortly after the siege, he was betrothed to and then married Ealswith, a Mercian woman.

In AD 869, the Vikings attacked East Anglia and killed its king, Edmund. They reorganized, conquered Reading, and headed for Wessex in AD 871. They stopped at a small village called Englefield. They were met by an ealdorman of Berkshire named Ethelwuf. After an intense battle, the Vikings retreated.

Ethelwuf reported the news of his victory to Ethelred, who prepared for battle and caught the Vikings by surprise. Ethelred’s troops were outnumbered and fled. Ethelwuf was killed.

Ethelred intercepted the Viking forces at Ashdown. He divided his troops into two groups, one led by him and the other by Alfred. Alfred and his men stood shoulder to shoulder with their shields overlapping one another, forming a continuous wall of protection (shieldwall). Alfred’s group pushed back the first group of men.

The Vikings sent the rest of their men to attack, but a second group of men, led by Ethelred, attacked the unprotected flank of the Viking’s shieldwall and they fled.

Two weeks later, the Vikings attacked Basing twice. The first time, Ethelred’s small army couldn’t hold their ground and retreated in humiliation. The second time, Ethelred had a larger group, but it wasn’t enough. The Vikings broke through the Wessex’s shieldwall and the men fled. Ethelred was gravely wounded. He died in AD 871 and Alfred became the king of Wessex.

3. His finest works

Shortly after Ethelred’s death, Alfred led his troops on an offensive attack on the Vikings at Wilton. The Vikings were beat back and retreated.

However, as the men of Wessex reveled in their victory, the Vikings regrouped and waged a second attack. The spirit was knocked out of Alfred’s men and they fled the scene.

After the battle at Wilton, the Viking’s entered into an agreement with Alfred to end their occupation of Wessex. Alfred paid the Vikings danegeld (a ransom paid for peace).

During AD 875 and AD 876, the Vikings attacked by sea and land. Alfred held them off at sea, but the Viking king, Guthrum, under the cover of darkness, was able to march through the heart of Wessex before capturing Wareham. Alfred arrived with his army after Guthrum had settled into their new fortress.

He considered his options and decided to pay Guthrum the danegeld. However, he made two extra demands. First, the two armies would exchange hostages, and second, Alfred insisted that Guthrum withdraw his men and swear on the holy ring of Thor (a special pagan relic).

The oath meant nothing to Guthrum. He killed the Wessex hostages and attacked Alfred while he and his kingdom were celebrating Christmas holiday festivities. After Alfred was cut off from summoning a fyrd (Saxon army) to help, he found himself defenseless and he, his family, and a few loyal men went into hiding. For more than four months, Alfred maintained a hiding place in Athelny and engaged in repeated guerilla warfare.

The Vikings had regularly exploited the Christian holy calendar to strike the Saxons. In AD 878, Alfred decided to turn the tables and called a meeting of all available men on Pentecost. They gathered at Egbert’s stone.

Alfred led the charge at Edington. The Vikings fled back to their camp at Chippenham. Alfred and his men waited two weeks. Guthrum finally gave up and sent a message to Alfred offering to leave without taking any Wessex hostages with him.

Alfred made another offer. He insisted that Guthrum accept the Christian God and be baptized. Alfred became his godfather. Guthrum accepted and Alfred named him Ethelstan. Alfred wanted to form a bond of kinship between himself and the conquered Viking ruler, hoping it would help maintain peace between the Saxons and the Danes.

During a few years of peace, Alfred restructured the unpredictable system of fyrds into a standing army. Defensive walls were built in selective cities which transformed them into a burh (fortified dwelling). A network of roads and public spaces were widened. Lastly, he renovated the Saxon currency to stimulate trade.

In AD 896, Alfred’s boats were doubled in size with sixty oars per ship. He recruited experienced Frisian sailors from the continent to train his men.

4. Alfred’s legacy

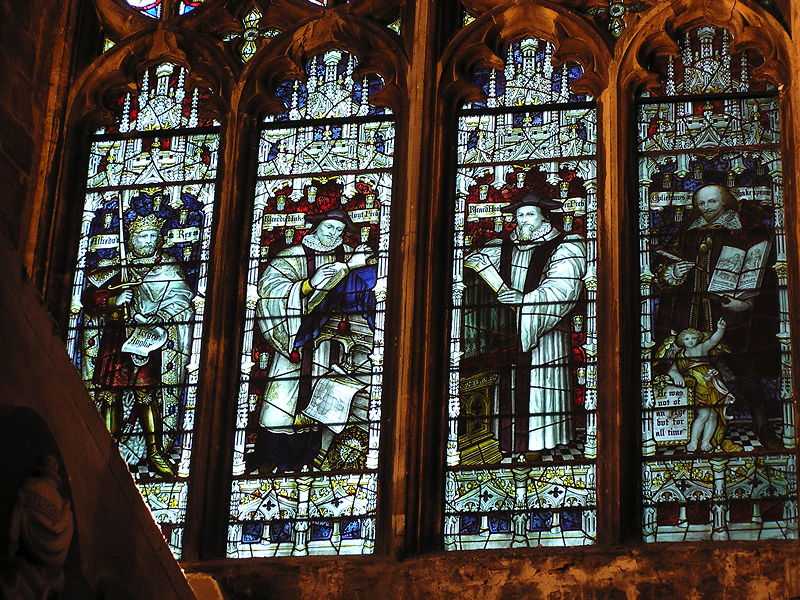

Alfred was King of Wessex from 871 to c. 886 and King of the Anglo-Saxons from c. 886 to 899. He was largely responsible for a substantial portion of the heritage and freedom that England enjoys today.

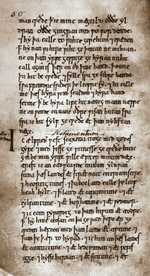

He enlisted the aid of Asser, a Welsh monk, to write his biography which offers vital information about Alfred’s reign. Also, he commissioned the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, which is an important reference for the history of the English language.

Alfred was given the title “Alfred the Great” by historians during the sixteenth century. It’s an honor well-deserved by this Anglo-Saxon warrior-king.

Alfred the Great died in AD 899 and was buried in the Old Minster in Winchester.