1. Cook’s Early Years and Education

James Cook was born on 7 November 1728 in Marton, Yorkshire.

Early life

Cook’s father, James, was a farmhand migrant from Scotland and his mother, Grace, was from Thornaby-on-Tees in North Yorkshire. Only two of Cook's seven siblings survived childhood—his older brother, John, and his sister, Margaret.

Education

At the age of eight the young Cook started working for a local farmer, William Walker. The boy tended to the Walkers’ horses and livestock, and ran errands. In exchange Walker’s wife Mary, who noticed that Cook was a bright child, taught him to read.

In 1736 Cook’s father became the foreman on a farm in a neighbouring village. Cook was an intelligent boy and as a result his father’s employer, Thomas Skottowe, paid for his education at the local village school until he was 12 years old.

After school

When Cook left the village school at the age of 12, he worked with his father as a farm labourer until he was 17 years old. After this he earned an apprenticeship in a store in a coastal village, Staithes, working for William Sanderson.

In Staithes Cook got into contact with the sea; the store where he worked was 300 yards from the sea.

The Walkers

After 18 months Saunderson took Cook to the nearby port town of Whitby; where he introduced Cook to his friends John and Henry Walker, who were shipowners in the coal trade. The Walkers employed Cook as a merchant navy apprentice for their small fleet of vessels.

Cook first worked on the bulk cargo ship Freelove along the English coast. He spent a few years between the river Tyne and London, working on Freelove and other coastal trading vessels.

At the time Cook studied mathematics, navigation and astronomy as part of his apprenticeship. Once he completed his apprenticeship, Cook started working on trading ships in the Baltic Sea. He was promoted to the rank of mate aboard the collier Friendship and was offered command of it.

2. Cook joins the Royal Navy

Less than a month after he assumed command of Friendship, Cook volunteered to join the Royal Navy in the wake of the Seven Years’ War (1756 and 1763).

Cook joined up at Wapping in East London on 17 June 1755.

HMS Eagle and first promotion

Cook first started serving on HMS Eagle, and he soon participated in the capture of a French warship and helped to sink another. After this he was promoted to the rank of boatswain.

Less than a year after he joined the navy he took command of Cruizer, a small vessel attached to Eagle. Two years after joining up Cook passed his master's examinations, which made him eligible to command a ship of the King's fleet.

Mapping the entrance to the Saint Lawrence River

After he passed his examinations, Cook joined HMS Solebay. He then worked on HMS Pembroke as a master during the Seven Years’ War. In Canada he participated in the capture of the Fortress of Louisbourg from the French in 1758, and in the siege of Quebec City in 1759.

Cook excelled as a surveyor and cartographer. During the siege of Quebec City he mapped the entrance to the Saint Lawrence River, which enabled Britain’s stealth attack on the French Army during the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in the same year.

Mapping the coast of Newfoundland

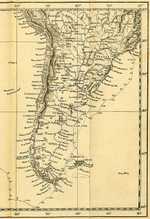

In the 1760s Cook, on HMS Grenville, mapped the coast of the Canadian island of Newfoundland to a high degree of accuracy and conducted astronomical observations.

He surveyed the north-west, south and west coast of Canada from 1763 to 1767.

Cook marries Elizabeth Batts

In 1762 Cook married the daughter of one of his mentors, Samuel Batts, who was the keeper of the Bell Inn in Wapping.

The wedding between Cook and Elizabeth took place at St Margaret's Church in Barking, Essex, on 21 December 1762. The couple's first son, James, was born the following year. James was baptised at the church Cook attended, St Paul's Church in Shadwell. Cook lived with his wife in the East End of London, but he was at sea most of the time during his marriage.

3. Cook’s First Voyage

Cook was commissioned by the Admiralty on 25 May 1768 to command a scientific voyage to the Pacific Ocean to observe the transit of Venus across the sun in 1769.

Departure

Cook was made a lieutenant to ensure that his status was sufficient to take command, and the expedition departed from England aboard HMS Endeavour on 26 August 1768.

Botanists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander were part of the expedition, and their mission was to retrieve plants from undiscovered territories. Cook was instructed to sail to Tahiti via Cape Horn. Endeavour stopped en route at Rio de Janeiro for supplies, and then at Tierra del Fuego at the tip of South America to get fresh water and wood.

At Tierra del Fuego the botanists on board collected plant specimens and an artist on board, Alexander Buchan, drew pictures of the local Huash people.

Tahiti

The expedition arrived at Tahiti on 13 April 1769. On Tahiti the explorers made friends with Tupaia, an aristocratic priest and navigator from the neighbouring island of Ra‘iatea. After observing the transit of Venus, of which their observations were inconclusive, the explorers departed to find signs of the hypothetical continent of Terra Australis.

They were joined by Tupaia, who guided them through the Polynesian Islands, and his servant Talato. If he were to find Terra Australis; Cook was tasked with examining the nature of the soil, fauna, flora and mineral wealth of the continent. He was instructed to collect botanical and mineral specimens as well.

New Zealand

Cook's expedition then reached New Zealand, which had already been discovered by Dutch explorer Abel Tasman. Cook’s orders were to explore as much of the coastline as possible.

New Zealand was inhabited by the Māori people who had moved there a few centuries earlier from the Pacific Islands. Cook first landed at a place called Poverty Bay, from where they explored the coastline further. The expedition was invited ashore by two chiefs at a place that Cook called Tolaga Bay.

At Tolaga Bay the botanists recorded the locals’ customs and collected artefacts, and the artists made drawings of the area. From there Endeavour made more landings on the east coast of New Zealand’s North Island. They then further explored the west coast, and landed at Queen Charlotte Sound at South Island.

Endeavour spent two months circumnavigating the island. Cook charted the island, and proved that it was not part of Terra Australis, which was the belief in Europe.

Australia

Cook’s expedition reached Australia’s east coast in April 1770. This made them the first recorded Europeans to discover Australia’s eastern coastline.

From there they sailed northwards and landed at a place that Cook later called Botany Bay. At Botany Bay Cook’s expedition encountered two hostile men armed with spears and stones, who tried to prevent them from coming ashore. Eventually the British fired at them, and one of the men was wounded in the leg.

For the following week Cook’s people and the local Gweagal people observed each other from a distance, but did not make contact. Further north Cook’s expedition encountered the Guugu Yimithirr people, also known as Kokoimudji. Cook’s expedition established a good relationship with them, and one of the British artists put together a vocabulary of their language.

The friendly relationship between the British and the locals did not last long because of their different customs, through.

Further north Cook landed on an island, which he called it Possession Island. On Possession Island he took possession of the whole Eastern Coast—from where Endeavour first sighted land up to New South Wales—in the name of King George III.

Batavia and illness

Further north in Batavia, Indonesia, which got known as Jakarta in later years, many of Cook’s expedition started falling ill.

Tupaia, Taiato and five other men died. On the way home more than twenty men died, including the astronomer who assisted Cook in charting New Zealand and Australia, Charles Green, and the artist, Sydney Parkinson.

Cook arrived at Kent in 1771, and he was made a commander in August that year. Even though Cook believed that the discoveries made during his first voyage were not great, he was seen as a hero back home in Britain after his scientific journals were published.

It was the start of the British colonisation of Australia when Cook took possession of the Eastern Coast, and he proved that New Zealand was not attached to a larger landmass to the south.

4. Cook’s Second Voyage

Scottish geographer Alexander Dalrymple and others belonging to the Royal Society believed that the hypothetical continent of Terra Australia existed somewhere south of Australia.

As a result, the Royal Society commissioned Cook in 1772 to search for this continent.

Departure

Five days after the birth of his son, George, Cook departed on his second voyage, commanding HMS Resolution.

He took along with him a chronometer made by British watchmaker Larcum Kendall, which would enable him to determine his longitudinal position with more accuracy than before.

He circumnavigated the globe at an extreme southern latitude, and on 17 January 1773 he crossed the Atlantic Circle, which is the most southerly of the major circles of latitude, that had never been crossed before.

Here, in thick fog, he became separated from Tobias Furneaux, the commander of Resolution’s companion ship HMS Adventure. Cook kept on exploring the Antarctic, and on 31 January 1774 he reached 71°10'S. Furneaux continued to New Zealand. After clashing with the Māori people and losing some men, he returned to Britain.

Tahiti and other islands

Close to Antarctica, Cook had to turn to Tahiti to resupply Resolution. Omai, a Tahitian guide, joined Cook’s expedition and they set sail southwards to find Terra Australis.

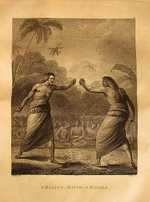

Cook landed at a group of islands where the inhabitants were so friendly that he named it the Friendly Islands, which got known as Tonga in later years. He stopped at Easter Island, where one of his Polynesian crew members, Hitihiti, was able to communicate with the local Rapa Nui people.

They also stopped at Norfolk Island, New Caledonia and Vanuatu in the South Pacific. He then took possession of the island of South Georgia for Britain. In addition, he discovered and named the South Sandwich Islands and Clerke Rocks.

Return to England

Resolution then set sail for England via South Africa. When he returned home, he confirmed that Terra Australia does not exist. The Larcum Kendall chronometer he took along enabled him to make accurate maps of the Southern Pacific Ocean, which were still used in the mid-1900s. Back home he was promoted to rank-captain, he was made a fellow of the Royal Society and he received the Copley Gold medal for losing nobody to scurvy during his second voyage.

Cook was made an officer at Greenwich Hospital in London, which was a permanent home for retired sailors of the Royal Navy. He accepted the position on the condition that he would be allowed to resign if an opportunity for active duty should arrive.

5. Cook’s Third Voyage

When a third voyage was planned shortly thereafter, Cook volunteered to find the Northwest Passage.

This passage is the sea route to the Pacific Ocean along the northern coast of North America. The public belief at the time was that the purpose of Cook’s third voyage was to return Omai—who had joined the expedition when they visited Tahiti the previous time—home.

Departure

Cook and his expedition left England on 12 July 1776. Cook commanded Resolution, and Captain Charles Clerke commanded HMS Discovery.

First European to reach Hawaii

After dropping Omai off at Tahiti, the expedition set sail northwards and reached the Hawaiian Islands in 1778. This made Cook the first European to make formal contact with Hawaii.

This first Hawaiian island they landed on was Kauai. Cook named Hawaii the Sandwich Islands in honour of the acting First Lord of the Admiralty, the fourth Earl of Sandwich.

He then set sail for northwards to explore the northern west coast of North America.

Searching for the Northwest passage

Cook’s expedition first stopped at Oregon, naming the place Cape Foulweather. They unwittingly sailed past the Strait of Juan de Fuca, through which the border between North America and Canada runs.

Cook’s expedition stopped at Yuquot in Canada. The British established a friendly relationship with the people of Yuquot, but at times these locals asked more valuable articles than the people of Hawaii had expected.

After this Cook's expedition explored the coast up to the Bering Strait between Russia and Alaska, and he mapped the coast along the way. At the time he identified what he called Cook inlet.

His expedition went through the Bering Strait, into the Chukchi Sea in the Arctic Ocean and up the Alaskan coast. When the expedition could proceed no further north due to ice, they then sailed down the Siberian coast to the Bering Strait and returned to Hawaii in 1779.

Hawaii

Cook sailed around the Hawaiian Islands for two months.

The expedition landed on Kealakekua Bay on Hawai'i island at the time of a Hawaiian worship festival for Lono, the Polynesian god. Resolution bore a resemblance to the Hawaiians’ religious artefacts in some way, and they came to believe that Cook was Lono that had arrived.

Cook's expedition left after a month to further explore the northern Pacific, but when Resolution's foremast broke they returned to Hawaii for repairs.

Back at Kealakekua Bay the relationship with the locals soured, and of the Hawaiians stole one of Cook's small boats.

Cook then decided to kidnap their king, Kalaniʻōpuʻu. Kalaniʻōpuʻu willingly left with Cook to their boats. On the way the pair were interrupted by one of the king's favourite wives, two chiefs and a priest. A large crowd from the island arrived at the scene, and it dawned on the king that Cook was his enemy.

6. Cook’s Death & Legacy

Cook turned around to launch the boats, and he was clubbed over the head by one of the chiefs and then stabbed by one of the king's attendants. Another four Royal Marines were killed and two were wounded as well.

Cook’s body preserved

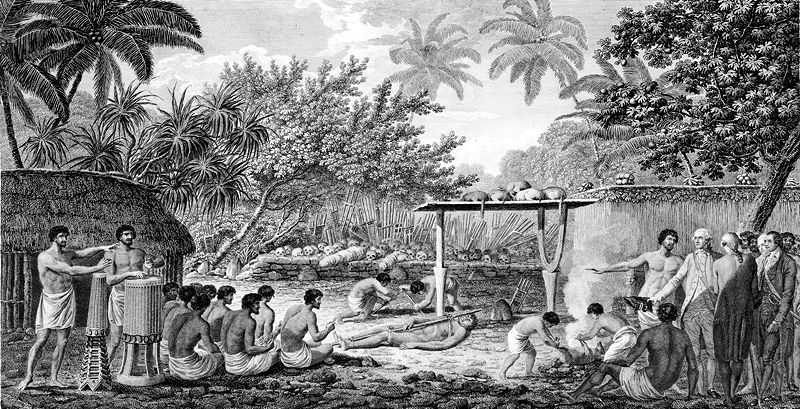

After he died, the Hawaiians carried Cook’s body away.

As they esteemed Cook, they decided to keep his body. They prepared his body applying the funerary rituals that they typically used for respected members of their society. These rites involved disembowelment of a body, and then baking it to make the removal of the flesh easier. The bones were then meticulously cleaned and preserved.

Cook laid to rest and the expedition returns home

The Hawaiians returned some of Cook's preserved remains to his crew. He was then formally laid to rest at sea. Clerke replaced Cook as leader, and tried to sail through the Bering Strait.

After Clerke died of tuberculosis, he was replaced by John Gore on Resolution. Gore was replaced by James King on Discovery. The expedition reached England in October 1780.

Elizabeth Cook’s reaction

Throughout her life—until she died 56 years after him— Cook’s widow showed high respect for his memory, and she wore a ring with a lock of his hair in it. She measured everything by Cook’s standards of honour and morality When she expressed disapproval, she would use the expression that "Mr Cook" would never have done that.

Before her death she carefully destroyed all her correspondence with Cook, as she considered this too sacred to share.

Cook Honoured and Remembered

Cook was honoured both during his lifetime and posthumously for his achievements.

Cook's image appeared on an Australian coin. In 1874 an obelisk in his honour was erected at the site where he was killed in Hawaii, and a life-size statue of him was erected in the centre of Sydney in Australia. A town in and numerous businesses in Hawaii are named after him. In addition, many places, institutions, landmarks and monuments in various countries are named after him.

Space shuttles have been named after Cook’s ships, and the Cook crater on the moon is named after him. In 1978 the Captain Cook Birthplace Museum was opened at his birthplace in Marton.

Cook’s Children

Cook had six children, five sons and one daughter. His daughter, Elizabeth, died nine years before him, and his sons Joseph and George died in infancy. His son Nathaniel died eight months after him, when his ship went down in a hurricane and he got lost at sea.

Cook's son Hugh, who was born in 1776—a few years before his death in 1780—died a few years after his father due to scarlet fever as a young student in 1783. The following year Cook’s eldest son, James, drowned.

Cook's children all died before they had children. Therefore, he had no direct descendants.