1. Early Life

Emmeline Pankhurst (nee Emmeline Goulden) was born on July 15, 1858 in the Moss Side district of Manchester. She was one of ten children and the eldest daughter of Robert Goulden, a merchant, and Sophia (nee Craine).

Pankhurst learned to read when she was three years old. Her parents were abolitionists and exposed her to a variety of literature that focused on the plight of people who sought their freedom from bondage. One of the bedtime stories that her mother read to her was Harriet Beecher Stowe’s book, Uncle Toms’ Cabin, a novel about slavery in America.

She read Thomas Carlyle’s three-volume treatise, The French Revolution: A History, which was a source of inspiration throughout her life. At the age of fourteen, Pankhurst accompanied her mother to a lecture given by Lydia Becker, a leader in the early British suffrage movement and who was editor of the Women’s Suffrage Journal. The meeting left a permanent impression on her.

Pankhurst’s parents were abolitionists and believed in women’s suffrage, but they did not support the idea of an extensive education for women. They believed that girls should learn a variety of social skills that would enable them to become good wives. Pankhurst rejected this notion and convinced her parents to send her to a progressive school in Paris. When she was fifteen, she enrolled in Ecole Normale Superieure, which believed in equal education for girls and boys. Girls were taught chemistry and other sciences as well as embroidery and bookkeeping.

In December 1879, at the age of twenty-one, Pankhurst married Dr. Richard Marsden Pankhurst, a lawyer. He was twenty-four years older than her. Pankhurst’s husband authored the first woman’s suffrage bill in Great Britain in the late 1860s and the Married Women’s Property (MWP) Acts in 1870 and 1882, which allowed women to keep earnings or property acquired before and after marriage.

2. Early Career

Pankhurst’s husband believed women could be more than housewives and mothers. He hired childcare help which enabled her to continue her political activities.

They had a large house in London and opened it to political intellectuals and activists, local as well as international. Among her earliest projects was serving with her husband on the committee which promoted the MWP.

In 1889, Pankhurst became a member of the Women’s Franchise League. It supported equal rights for women in the areas of divorce and inheritance. The group prepared a women’s suffrage amendment to a new reform act, the County Franchise Bill, which extended the suffrage to farm laborers. A promise by a member of Parliament to submit the amendment was made, but Pankhurst learned that he had no intention of keeping it.

During the 1890s, Pankhurst and her husband had some financial problems. They returned to Manchester. She served on the Board of Poor Law Guardians in Chorlton. Her experiences with poor women were disheartening. She believed improvements were unlikely without the vote.

In 1898, Pankhurst’s husband died. They’d had five children, three girls and two boys. One boy had died in childhood, but she was still responsible for the four at home. Faced with mounting debt, she took a position as Registrar of Births and Deaths where she encountered young teenage mothers who had myriad problems.

In 1900, Pankhurst attended a lecture given by Susan B. Anthony, an American suffragette. The lecture and the urging of her daughter, Christabel, led to the forming of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1903. She decided that she would keep it simple: women only, no other party affiliation, and action only. It would be a political action organization with “deeds, not words,” as its motto. They also published a newspaper, Votes for Women.

3. Finest Works

From the outset, as Pankhurst presented concerns to members of Parliament, she was met with broken promises. She remembered the tactics of the agricultural laborers.

They had won their franchise by burning hay ricks, rioting, and threatening to organize one hundred thousand men and descend on the House of Commons. She decided that she would thrust the disenfranchisement of women into public consciousness.

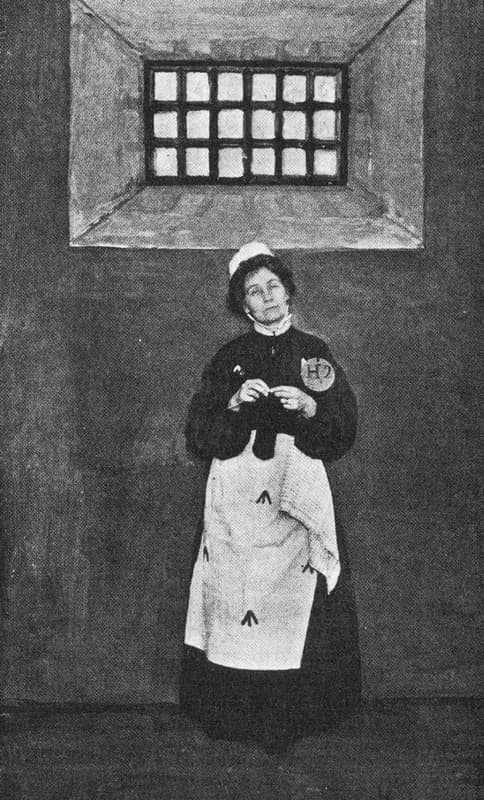

In 1905, after submitting a women’s suffrage resolution to a member of Parliament and being patronized and placated, her first militant act was to go outside the House of Commons and protest. Although there was some heckling from onlookers, the experience was invigorating. In 1908, Pankhurst submitted another women’s suffrage resolution to a member of Parliament. Once again, promises were made and broken. She and her supporters held a large protest demonstration and she was imprisoned. While in prison, she was shocked by the appalling condition and decided to use prison to exercise the urgency of women’s suffrage.

In 1909, Pankhurst decided that her group would campaign against candidates who did not make the vote for women a priority. Their actions led to the defeat of several candidates for office or a close call. Notably among these candidates was Winston Churchill.

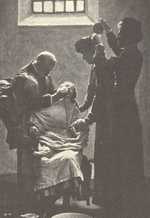

In addition to throwing rocks and breaking windows, Pankhurst and her group added hunger strikes to their methods. This led to force feeding in prison which caught the media’s attention. In 1913, the government passed the Temporary Discharge for Ill Health Act, known as the Cat and Mouse Act. This law allowed prisoners who were being force-fed to be discharged from prison.

In 1910, Pankhurst began a series of speaking tours abroad. Her first visit was made on behalf of her son, Henry Francis. He was ill and she needed the money for his treatment. He died shortly after she returned. In that same year, Pankhurst and her group were subjected to extreme violence during a demonstration termed Black Friday. On November 18, 1910, one hundred and fourteen women and two men were brutally beaten, arrested, and imprisoned.

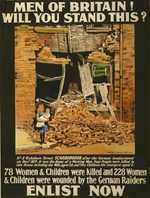

When World War I began in 1914, Pankhurst and the WSPU stopped their suffrage activities and focused on the war. She believed that the threat from Germany was a threat to humanity and she became a patriotic advocate. She also took an interest in children borne out of wedlock and adopted four. Unlike Christabel, her other daughters, Sylvia and Adele, were pacifists and opposed conscription. They left the WSPU.

In 1917 the WSPU became the Women’s Party. Women were permitted to stand as candidates and Pankhurst’s daughter, Christabel, decided to run for Parliament. She was unable to get the necessary support from the Coalition Government and lost to a Labour candidate.

After the Representation of the People Act which granted the vote to women over thirty was passed in 1918, Pankhurst continued to travel abroad speaking on various issues and rallying support for the British Empire.

In 1926, Pankhurst joined the Conservative Party and became a candidate for office. She died shortly before the passage of the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928 which extended the vote to all women over twenty-one years of age.

4. The Legacy

Pankhurst was a brave and courageous woman who stood up for what she believed and was willing to risk everything in pursuit of her goal.

Admittedly an autocrat where her organization was concerned, but she loved her country and spent over four decades trying to get it to reciprocate.

Pankhurst brought democracy to Britain when women were granted the right to vote, but historians have criticized her for some of her militant tactics, especially arson.

However, her actions pale when compared with the “Peterloo Massacre” in 1819, which historians regard as the bloodiest political event of the nineteenth century on English soil or the Swing Riots in 1830. Emmeline Pankhurst died on June 14, 1928 shortly before she saw the fruition of her life’s work. On March 6, 1930, a statute of her was placed in Victoria Tower Gardens next to and gesturing towards the Houses of Parliament.

![The Women's Social and Political Union became known for its militant activity. Pankhurst once said: "[T]he condition of our sex is so deplorable that it is our duty to break the law in order to call attention to the reasons why we do."](/static/9ddd78d0d7f9b7bb1218811a87747f13/14b42/emmeline-pankhurst-political-union.jpg)