1. Early Life

Marie Charlotte Carmichael Stopes was born October 15, 1880 in Edinburgh, Scotland to Henry, an engineer, and Charlotte (nee Carmichael).

Stopes was homeschooled until she was twelve. Her father’s real interest was archaeology and she would visit him on his various excavations. Her mother was a Shakespearean scholar who had earned a University “certificate.” Degrees were not awarded to women in Great Britain during the Victorian era, even though she had done the same work as the male students.

From 1892 to 1894, Stopes attended the St. George’s School for Girls in Edinburgh. Later, she was sent to the North London Collegiate School.

In 1900, Stopes won a scholarship to the University of London. While there, she also attended day and night school at a University of London affiliate: Birkbeck, a public research university. In 1902, she graduated with a first-class B.Sc. in botany and geology and later a D.Sc. In 1904, she earned a Ph.D in botany at the University of Munich.

2. Early Career

In 1904, Stopes accepted a position as a lecturer in palaeobotany at the University of Manchester. She was the first female academic in the school’s history. Stopes began her career classifying coal.

The was a ‘hands on’ scientist. She climbed down into the mines in Lancashire and collected 300 million-year-old plant fossils. This work was significant, because it shed new light on the origin of coal, distinguishing it from coal balls which are nonflammable and useless for fuel.

In 1907, The Royal Society sent Stopes on an eighteen-month expedition to Japan. At the Imperial University in Tokyo, she studied the Horonai coal mine for fossilized plants, the oldest mine of the Ishikari coalfield of the Sorachi region on Hokkaido island.

Stopes became a rising star in the British science community and in 1910 she was commissioned by the Geological Survey of Canada to study the Fern Ledge, a geological structure at St. John, New Brunswick and help resolve a dispute about its age. In that same year she met Canadian geneticist Reginald Ruggles Gates. Within two days, they were engaged. In March 1911, they married and returned to England.

Stopes finished her research for Canada and her work was published in 1914. Her marriage was not successful and was annulled in 1916.

3. Finest Works

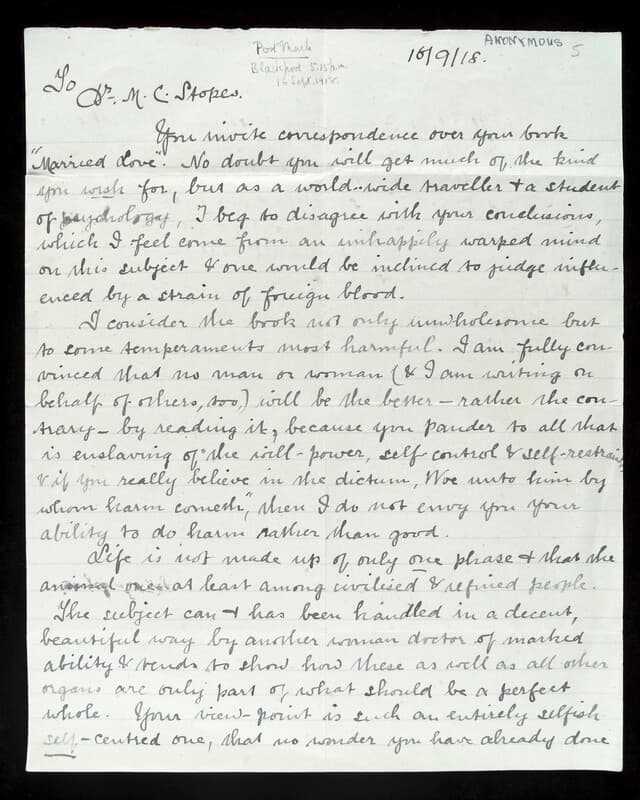

Stopes’s failed marriage had a profound psychological effect on her and before her marriage officially ended, she began writing a book on how she thought marriage should be.

During that same time, Britain was involved in World War I and she was commissioned by the British government to study coal. Coal, at the time, had huge economic importance. In addition, it was the fuel that heated homes. In 1918, she and R. V. Wheeler wrote Monograph on the Constitution of Coal. Later, in 1918, she met Humphrey Verdon Roe, a wealthy businessman.

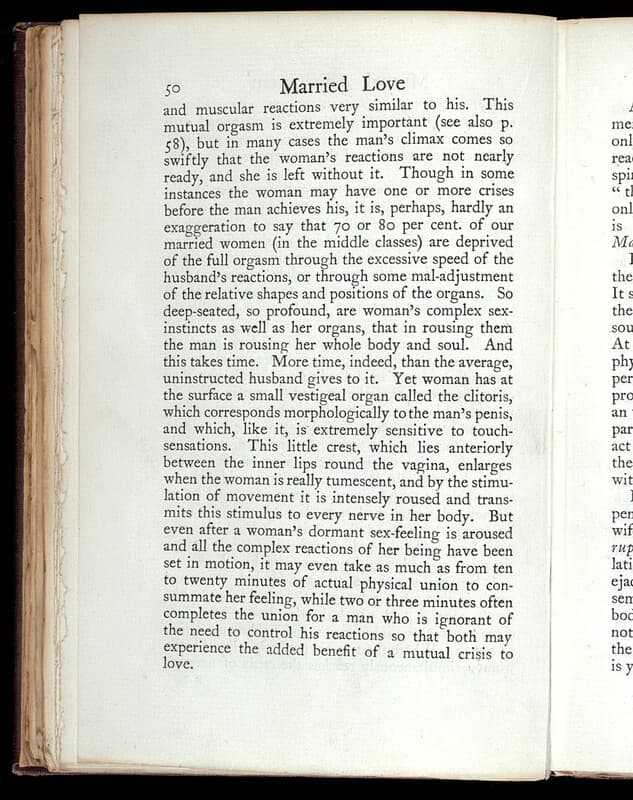

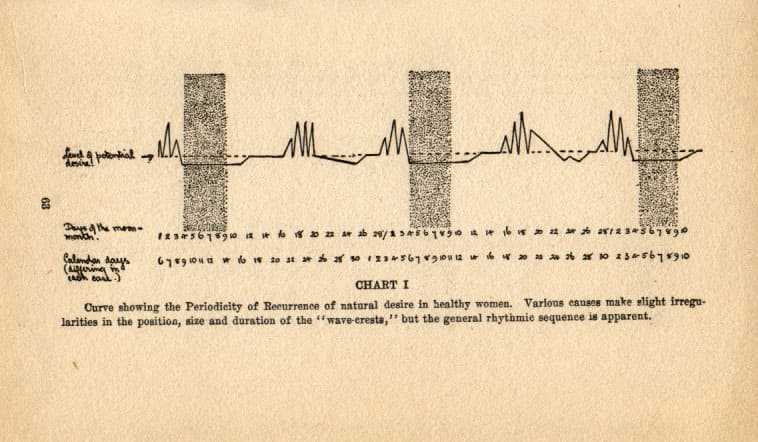

Her book Married Love had been rejected by a publisher because it was felt it was too controversial. Roe was interested in birth control and ‘bankrolled’ her book. On March 26, 1918, Married Love was published. It was an immediate success which elevated Stopes to national prominence. Two months later, Stopes married Roe. Shortly, after her marriage, Stopes published Wise Parenthood: A Book for Married People, a follow-up to Married Love.

In 1921, Stopes, supported by her husband, founded the Mothers’ Clinic in the working-class Holloway district of London. It was the United Kingdom’s first instructional clinic for contraception. She had been influenced by Margaret Sanger, an American, who in 1916 had opened the first birth control clinic in the United States.

Following the opening of the family planning center, Stopes founded and became president of The Society for Constructive Birth Control and Racial Progress. During the inter-war years “birth control” became a contested political issue. The term was equated with “eugenics.”

In 1922, Dr. Halliday G. Sutherland wrote Birth Control: A Statement of Christian Doctrine Against the Neo-Malthusians. In it he referred to Stopes as “a doctor of German philosophy.” One of his chapters discussed how Stopes’s clinic was exposing the poor to experiments which implied that something unseemly was occurring at her family planning clinic.

Stopes believed Sutherland was trying to undermine her because she was not a medical doctor and given it was so soon after World War I stir up anti-German sentiment. She brought a writ for libel against him. She won the first round, but during a second trial Sunderland won. Allegedly, he had been financed by the Catholic church.

In 1923, Stopes published Contraception: Its Theory, History, and Practice. It was the most comprehensive treatment of the subject. In the following year, she gave birth to her second child, Harry Verdon Stopes-Roe, on March 27, 1924. Her first child in 1919, a boy, had been stillborn.

In 1925 she moved the Mothers’ Clinic to Central London. She built small networks of clinics and worked to fund them. Other birth control societies were formed. In 1930, several societies merged and the Family Planning Association (FPA)was formed.

Stopes divided her activities between science and humanitarian endeavors. After her second child, she was advised not to have any more children. Convinced her son needed a companion, she advertised for one. She was accused of“micromanaging her son’s life. Over the years, her son rebelled and stood up to her.

Stopes wrote eight books between the years 1918 to 1928. They were controversial publications on sex and birth control. She was a member of the Eugenics Society and believed that eugenics was an extension of mother love. Her book Radiant Motherhood best reflects this opinion. Stopes wrote poems and plays. Her first major success was Our Ostriches, a play that dealt with society’s approach to working class women being forced to produce babies throughout their lives.

Stopes was a staunch activist. She thrived on adversity and relished being controversial. As time went on her inability to accept criticism and her defensiveness alienated her friends and valuable allies.

4. The Legacy

Samuel Butler wrote, “Academic and aristocratic people live in such an uncommon atmosphere that common sense can rarely reach them.”

Marie Stopes was academically brilliant, but when one reviews her personal life, one is struck by what seems to be a certain naivete coupled with arrogance, e.g., her first marriage was annulled because of ‘non-consummation’ after five years and her second marriage failed as a result of her forceful personality.

There was no divorce, but her husband signed an agreement that gave her permission to take on lovers. Stopes was a dedicated feminist with superb academic credentials. Her apparent ignorance regarding the facts of human sexuality even in the early twentieth century is surprising, but Stopes should be given credit, because she sought legal help on her own and got her marriage annulled.

Stopes’s life is riddled with lax in judgment. In 1928 a physician friend described her as suffering from paranoia and megalomania. However, her contributions as a feminist and a scientist should not be dismissed.

Stopes was not a trained psychologist, but her books Married Love and Wise Parenthood proved to be useful, albeit there was a long philosophical struggle with the Church of England. Today, her clinics, Marie Stopes International, are worldwide and provide a valuable service.

Stopes was hard-nosed and never forgave her son for marrying a woman she thought was beneath him. Ironically, when she died on October 5, 1958, it was her son and her current lover who scattered her ashes from a cliff into the sea.