1. Early life

Named after her place of birth in Italy, Florence Nightingale was born 12th May 1820, a second daughter to William and Frances Nightingale.

Her parents were on an extended honeymoon when she was born and returned to England the following year, spending time between their two residences in Derbyshire and Hampshire. Her father was keen for Florence to have a classical education and she became especially interested in Mathematics. She was already displaying her philanthropic side too, helping the sick and poor in the neighbouring villages.

Florence Nightingale was growing up in an era when the daughter of wealthy families did not have a profession. They were expected to marry a man of means, but this did not fit with Florence Nightingale’s view on life. She refused a marriage proposal from a Gentleman by the name of Richard Monckton Milnes.

She felt it was God’s calling for her to help lessen human suffering and looked upon nursing as the best way she could meet such a calling. Her parents initially forbade her to pursue this line, but the persuasive Florence made them relent and in 1850 she enrolled in three weeks nursing training at a school in Düsseldorf, Germany.

While in Germany Florence Nightingale learned important lessons in nursing as well as skills in hospital organisation. By 1853 she had returned to London to work at a Harley Street hospital for ‘gentlewomen’ where she was soon made a superintendent. However, October 1853 saw the start of the Crimean War, with Britain joining its French and Turkish allies in a bid to halt Russian expansionism. It was a conflict which changed the life of Florence Nightingale and the history of nursing.

2. Crimea

Within 7 months of the outbreak of war reports were reaching home of the awful conditions the wounded soldiers were having to suffer, with a lack of even the most basic medical supplies.

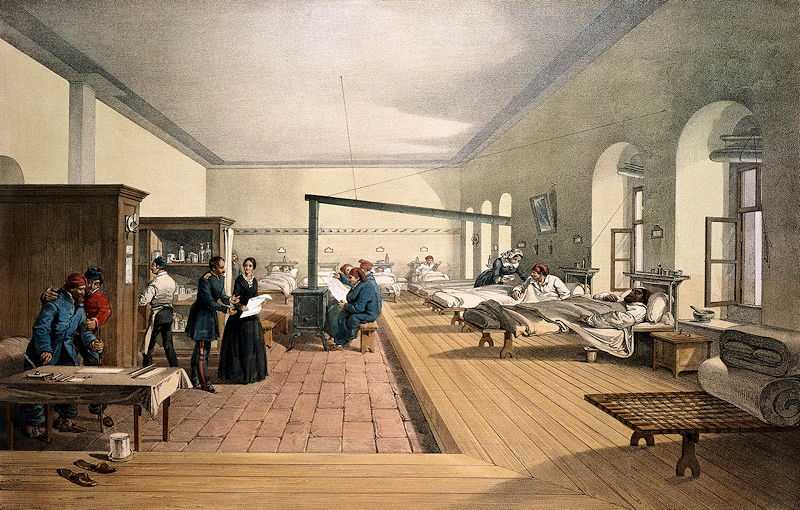

The Secretary of War at that time was Sidney Herbert, who was also a social acquaintance of Florence Nightingale. Herbert invited her to help organise a team of nurses to tend to the wounded in Crimea and in November 1854 she arrived at the military base hospital of Scutari in Constantinople with 38 female nurses. For all the reports they may have received in advance, the team were still shocked by what they found on arrival, with Florence Nightingale remarking the military hospital was the “kingdom of hell”.

She wasted no time in organising better supplies and better cleaning standards. The hospital was scrubbed clean from top to bottom, regular cleaning and bathing for patients was introduced and a laundry room was established to consistently provide clean linens. Florence Nightingale recognised the importance of good food in aiding recovery and ensured the kitchen had the necessary supplies to properly feed the wounded men. She also addressed the mental health of her patients, appreciating the importance of helping them write home to loved ones, while also providing recreational and educational facilities.

There had been initial stubborn resistance to her team when they first arrived, but for any remaining doubters the proof was surely in the proverbial pudding. The changes implemented by Florence Nightingale and carried out by her and her team drastically cut the mortality rate. She would put to good use her love of mathematics to illustrate the need for reform with statistical charts showing how more men had died from disease then from their wounds.

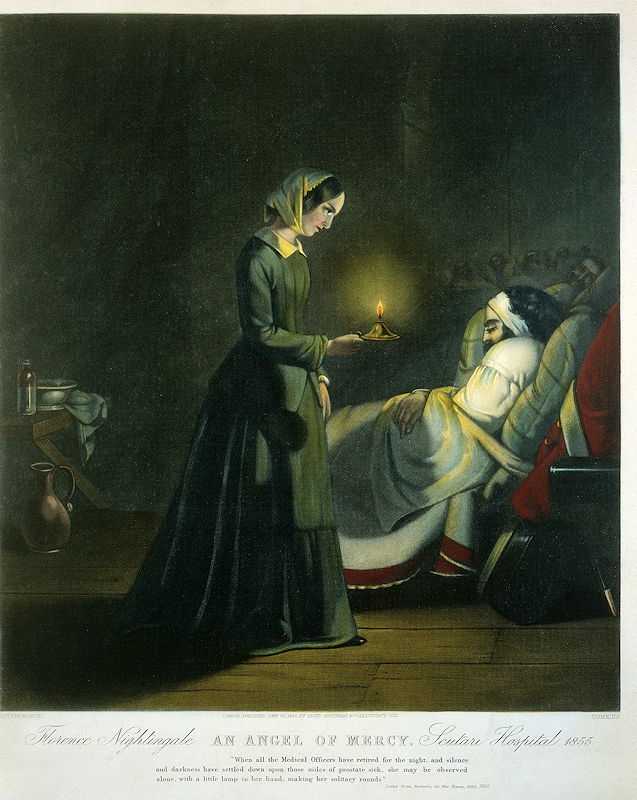

Her devotion and care to the individual soldiers, including her famed night time checks, earned her their eternal gratitude and undying respect. She was to stay in Crimea for 18 months, returning home in the summer of 1858 to a hero’s welcome.

3. Social Reform

Back in England the Nightingale Fund was established and donations poured in. A large part of this fund was used to establish a nursing school at St Thomas’ Hospital in London in 1860.

This school was hugely significant in seeing women aspire to be nurses and for it to be seen as acceptable to work outside of the family home. Nurses from this school would soon be invited to set up nursing schools around the world, including in Australia, Africa and America.

Florence Nightingale was prolific in her writing on nursing, health and social reform but one book would prove vital in influencing better hygiene in households up and down the country. “Notes on Nursing: What it is and What it is Not” was published in 1859 and has not been out of print since. This was written as a purely practical guide aimed at those who were looking after people at home with everyday health problems, and not as a manual on how to become a nurse.

With the aid of the Nightingale Fund further reforms were made and a school to educate midwives was founded in 1862. Training for district nurses was also encouraged as she felt people recover better in the comfort of their own homes. While overseeing reforms in hospitals at home, Florence Nightingale did not forget the British Army, advising on how poor drainage and ventilation, plus overcrowding contributed to a high death rate in India. She had the foresight to recognise that the health of the Army was interlinked to that of the population and campaigned for better sanitation in India as a whole.

4. Later Life and Legacy

From the late 1850’s Florence Nightingale suffered with poor health and was often bedridden.

It is believed she may have suffered with a bacterial infection called brucellosis, which she probably contracted while in Crimea. However this did not put a halt to her campaigning spirit as she was still able to send off around 13,000 letters over the years supporting and championing her various causes, with part of this correspondence being between her and Queen Victoria.

Her work had not gone unnoticed abroad either and during the American civil war she was often consulted for advice on the best management practices for field hospitals. In 1883 she was the first person to receive the Royal Red Cross, a decoration introduced by Queen Victoria to honour exceptional services in military nursing. In her lifetime she was further honoured with the title Lady of Grace of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem and by being the first woman awarded the order of merit.

With failing eyesight Florence Nightingale’s correspondence tailed off over the last decade of her life. She died on 13th August 1910 at her home in London, aged 90. She had never married and her relatives turned down the offer of a national funeral and burial in Westminster Abbey, honouring her wishes to have a modest burial service instead. Florence Nightingale was laid to rest by the side of other members of her family in the graveyard of St. Margaret’s Church in East Wellow, Hampshire.

Two years later in 1912 the International Committee of the Red Cross introduced the Florence Nightingale medal, which is the highest distinction a nurse can receive and is awarded for outstanding service. The ‘Lady with the Lamp’ also has her birthday recognised each year with May 12th having been International Nurses Day since 1965.

Florence Nightingale was a pioneer for modern nursing and health reform. Yet she never lost her love for mathematics either and often used charts in her reports, including to illustrate the sources of seasonal deaths at field hospitals. In 1859 she became the first woman to be elected a member of the Royal Statistical Society.

During a remarkable life she helped bring about much needed reforms in health and sanitation, but perhaps equally important she changed the perceptions of what women of her class could do with their lives. Thanks to Florence Nightingale nursing was now a profession a family was proud for their daughter to undertake.