1. Bacon's early life

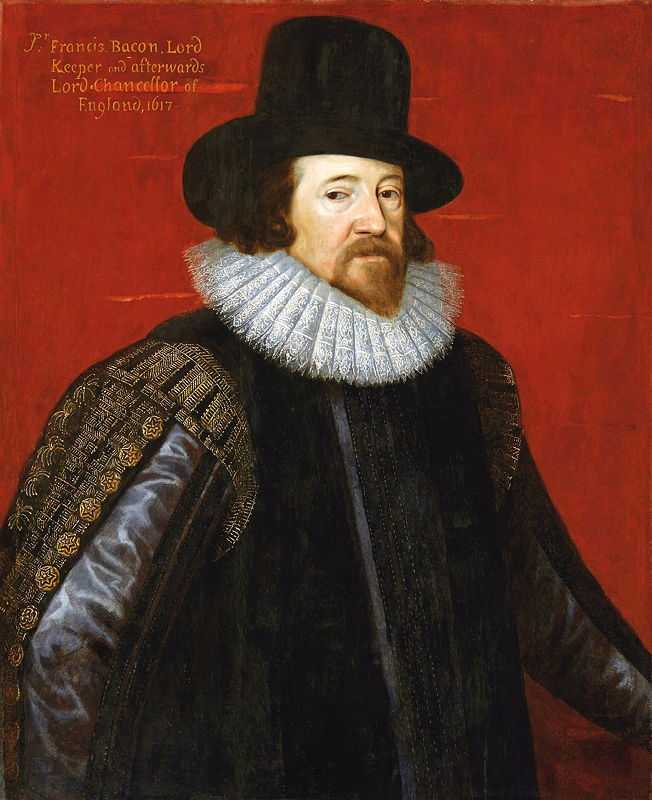

Francis Bacon, Viscount St. Alban, was born on January 22, 1561 in a prominent wealthy family at York House in London.

He was the youngest son of Sir Nicholas Bacon, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal to Queen Elizabeth I, and his second wife, Anne Cooke, daughter of the noted Renaissance humanist, Anthony Cooke.

Bacon was homeschooled until he was twelve years old. In 1573, he and his older brother, Anthony, went to Trinity College at the University of Cambridge under the personal tutelage of Dr. John Whitgift, future Archbishop of Canterbury. His education was conducted in Latin and followed the medieval curriculum. During his three years at Cambridge, he questioned the methods and results of science as then practiced, particularly Aristotelian philosophy.

In 1576, Bacon and his brother, Anthony, entered Gray’s Inn, a professional association for barristers and judges. After a year, Bacon interrupted his studies and went abroad with Sir Amias Paulet, English Ambassador to Paris. For the next three years he visited various parts of France, including Blois, Poitiers, and Tours, as well as Italy and Spain.

Bacon performed routine diplomatic tasks, such as delivering diplomatic letters to England for Walsingham, Burghley, Leicester, and Queen Elizabeth I. During his stay in Poitiers, he studied at the University of Poitiers.

In 1579, Bacon’s father died which necessitated his return to England. Bacon’s father did not complete his inheritance plans and Bacon was left with only one-fifth of the inheritance his father had intended. Bacon had borrowed money and was in debt. Assisted by a grant from his mother, Bacon was able to resume his residence in law at Grays Inn.

2. Early career

Bacon’s maternal uncle, William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, had close ties with Queen Elizabeth I and he hoped that his uncle would assist him in his professional endeavors.

When his uncle did not, Bacon pursued the law and politics. His first break occurred in 1581. An office became vacant between general elections, and he was elected as a member of parliament (MP) for Bassiney, Cornwall.

In 1582, Bacon passed the bar and assumed a position as outer barrister. Two years later, he took a seat in Parliament for Melcombe in Dorset in 1584. In that same year, Bacon wrote a letter to Queen Elizabeth I. It was titled A Letter of Advice to Queen Elizabeth I.

In it, he offered a proposal for outlining a new system of the sciences, emphasizing empirical methods, and laying the foundation for an applied science. The Queen viewed Bacon’s ideas as too ambitious and impractical and was not supportive.

Undeterred by the Queen’s response to his letter, Bacon turned his attention back to law and politics. He became a bencher at Grey’s Inn in 1586 and was elected an MP for Taunton. During that same period Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots, Queen Elizabeth I’s sister, was accused of plotting against Elizabeth. Bacon was a part of Parliament that urged her execution.

In 1587, he became a reader at Grey’s Inn and delivered his first set of lectures the next year at Lent. In 1588, he was elected to serve as MP for Liverpool.

Bacon had a reputation as a liberal minded reformer eager to amend and simplify the law. In 1591, he met Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex and became the Earl’s confident advisor.

In 1593, he was elected to serve as MP for Middlesex followed by an MP position in Ipwich in 1597. In that same year, he wrote the first of his Essay series. The first consisted of ten essays and was titled Essayes. Religious Meditations. Places of Perswasion and Disswasion Seene and Allowed.

Also, he became the first Queen’s Counsel designate and received a patent giving him precedent at the Bar. However, Bacon consistently had a problem with his finances and, in 1598, he was arrested for debt.

Bacon didn’t lose favor with the Queen for his misdeed. Several years later, he found himself involved in court proceedings concerning the Earl of Essex. Essex had been his friend and patron and the Queen’s favorite, but Essex was headstrong and wouldn’t heed Bacon’s advice. He was accused of plotting against the Queen. He was found guilty and executed in 1601. In that same year, Bacon assumed a second term for MP for Ipwich.

3. His finest works

In 1601 Queen Elizabeth I died. After serving her for over twenty years, Bacon had been passed over several times and never received any substantial promotions.

In 1603 King James I took the throne and life changed for Bacon. In that same year, he was one of three hundred knighted by the king. Also, Bacon’s writing ability was enhanced. He, along with William Shakespeare, John Donne, and Ben Jonson are hailed as contributing to a flourishing literary culture.

In 1605, Bacon published Of the Proficience and Advancement of Learning, Divine and Human, considered by some biographers as a pioneering essay in support of empirical philosophy.

On May 10, 1606, Bacon married Alice Barham, the daughter of Benedict Barham, a London merchant who held the positions of Alderman, Sheriff for London, and MP for Yarmouth and Dorothy Smith. Bacon was forty-five and his bride fourteen. Some biographers assert that it was a political marriage.

In 1607, he was appointed Solicitor General. The next year he assumed a Clerkship position in the Star Chamber dealing with real property transactions (reversion) that he had been given in 1589 but the position had been deferred until 1608.

Bacon continued to advance in his career. In 1612 he was appointed Attorney General. In that same year he added thirty-eight more entries to his Essay series. While serving as Attorney General, he was also elected MP to serve Cambridge University in 1614 and in 1617, he was appointed Lord Keeper of the Great Seal. In 1618, Bacon became Lord Chancellor and was created Baron Verulam. Three years later he was created Viscount of St. Albans.

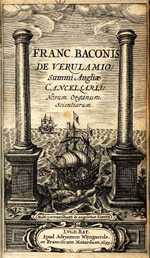

In 1620, Bacon wrote Novum Organum (‘new method,). In this piece he offered what he believed to be the true direction concerning the interpretation of nature.

4. Bacon's legacy

Truth and politics are not always compatible, as Bacon soon discovered. He accepted aid from influential patrons, notably the Earl of Essex. Some historians consider his role in the execution of the Earl of Essex as a blot on his record.

Bacon didn’t endear himself to Queen Elizabeth, if he disagreed with her, but his major downfall came in 1621. He raised the ire of the Duke of Buckingham when he argued against monopolies, indirectly attacking the Duke, who was the king’s favorite.

The tables were turned on Bacon and he found himself in a situation where he was accused of taking bribes. Bacon admitted accepting gifts, but he denied that the gifts influenced his decisions. The efficacy of explaining the positive or negative aspects of a ‘quid pro quo’ probably seemed pointless and he determined that he “had to go along to get along” and pleaded guilty to save the Duke from public anger and open aggression.

He was impeached by Parliament, heavily fined, sentenced, removed from Parliament, and lost all offices. Later, the fine was waived and the sentence reduced. He retained his titles and personal property.

Bacon retired to his home in Gorhambury in Hertfordshire and devoted the last five years of his life to philosophical work. In 1625, he added fifty-eight more entries to his Essays, titled Essayes or Counsels, Civil and Morall.

Shortly thereafter, Bacon and his wife, Alice, became estranged. Bacon rewrote his will. He wrote

“What so ever I have given, granted, conferred, or appointed to my wife in the former part of this my Will, I do now for just and great causes, utterly revoke, and make void, and leave her to her right only.”

Bacon left behind a cultural legacy, but he also influenced the consolidation of the United Kingdom and advocated for the union of England and Scotland and for the integration of Ireland into the Union.

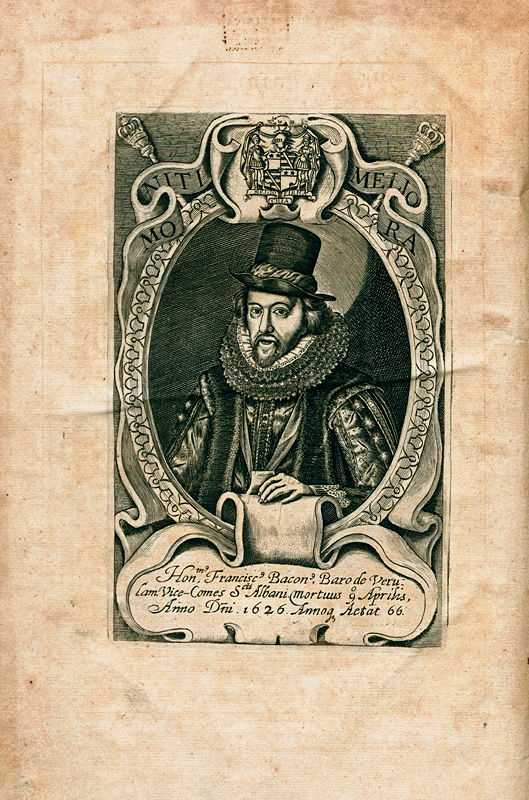

Bacon died April 9, 1626 of pneumonia. He was buried at St. Michael’s Church, St. Albans, Hertfordshire. He had no heirs and his titles became extinct.