1. Lionheart's early life

Richard the Lionheart was born on the 8th September 1157 at Beaumont Palace in Oxford.

He was the third son born to King Henry II and Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, and as such he would probably not have expected to ascend to the throne.

His early childhood was most likely spent in England and constituted a major proportion of the total time he spent in the country throughout his life. Richard seems to have been Eleanor’s favourite and she took him with her on a visit to Normandy when Richard was aged 8.

At the age of 11 Richard was given control of the Duchy of Aquitaine and three years later in 1172 was invested in his mother’s inheritance of both Aquitaine and Poitou.

His father King Henry II had been taken ill and had decided to give all four of his sons their inheritance early in order to see them established in their own right before he died. As well as his inheritance Richard was also betrothed to Alys who was the daughter of King Louis VII of France. This was to prove quite a long-term engagement.

However King Henry II ensured he retained overall authority of the lands. His eldest son, known as Henry the Young King, wanted more independence and now, as heir to the throne after the early death of the first born son William, he rebelled against his father.

Richard joined the rebellion, as did another brother Geoffrey. They also sought the support and protection of the French King, Louis VII. However the rebellion was put down by their father who raised a formidable army and the brothers all begged forgiveness, which was duly given.

Queen Eleanor had attempted to join up with her rebellious sons, but was captured and imprisoned for the remainder of the reign of King Henry II.

2. King Richard I and the Third Crusade

King Henry II was once again in the process of dealing with the ambitions of his sons when Henry the Young King, heir to the throne, suddenly died in 1183.

Richard had put down baronial revolts in Aquitaine, but the rebels had asked his brother Henry for assistance. However with the sudden death of Henry the Young King, Richard was now heir to the throne.

Yet old family habits die hard and when King Henry II wanted Richard to give up Aquitane to his younger brother John, he once again rebelled against his father, paying homage to the French king’s son Phillip II in return for assistance. In July 1189, amid this dispute, King Henry II died and Richard ascended to the throne.

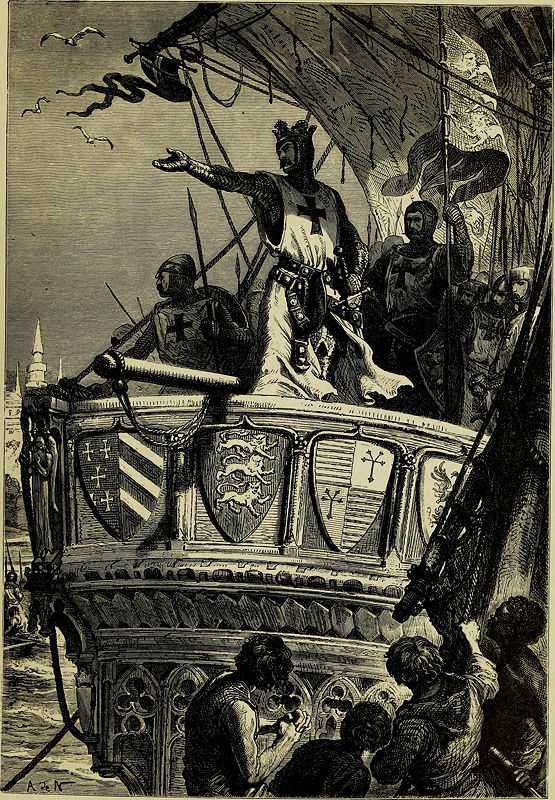

The new king, crowned Richard I, immediately turned his attention to the Third Crusade following the capture of Jerusalem by Saladin in 1187. He looked to his newly acquired realm of England as a source to fund his crusade, raiding the treasury and initiating a levy known as the ‘Saladin Tithe’ for this purpose. He was joined by Phillip II, but the voyage to the Holy Lands was anything but straightforward.

In September 1190 they arrived at Sicily where Richard’s sister, Joanna, who had been married to the island’s former king, had been imprisoned by the new king Tancred. He refused to return her dowry, but changed his position and released Joanna when Richard once again showed why the Lionheart tag was well earned as he took the city of Messina.

It was also on Sicily where King Richard slighted Phillip II, to whose sister he was still betrothed, informing him he actually intended to marry Princess Berengaria of Navarre who was being escorted to the island by Richard's mother.

After departing Sicily the fleet of ships was hit by a storm with some forced in to waters off Cyprus. King Richard’s family were safe but prisoners and goods were taken from other ships under the watch of the island’s ruler Isaac Comnenus.

When he refused to release the prisoners and return the stolen goods Richard the Lionheart responded in the way he knew best, invading Cyprus and taking the island for England. Richard also married Princess Berengaria while on Cyprus, further damaging his relationship with Phillip II.

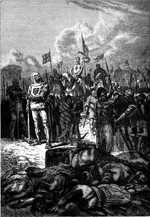

In June 1191, Richard the Lionheart finally arrived in the Holy Land. Within a month of his arrival the besieged Acre was captured, although Phillip II had arrived in advance of Richard and his work to mine the walls had contributed to its ultimate fall. In a crusade dominated by personal feuds and arguments, Phillip II decided to head home following the fall of Acre.

Richard the Lionheart would also come to regret throwing the standard of Leopold V of Austria from the walls in a dispute over dividing up the spoils of victory. Richard went on to win a victory at Arsuf, before reaching the foothills of Jerusalem on the 3rd January 1192. With supplies short and sickness in the ranks it became all too evident that they would not be able to take Jerusalem and Richard agreed a truce with Saladin.

The truce agreed that the crusaders would keep Acre plus a strip of coastal land where Christian pilgrims could come ashore to visit the sacred sites.

3. Imprisonment and Later Life

It was on the return home when King Richard’s feuds with his fellow crusaders caught up with him.

He decided to travel via the Adriatic to avoid territory belonging to Phillip II.

However, a storm forced him ashore near Venice, before being taken prisoner having reached as far as Vienna. He was imprisoned in the castle of Durrenstein by Leopold V who Richard had insulted at Acre when throwing Leopold’s standard from the wall.

Leopold then handed Richard over to the German emperor Henry VI whose alliances had been put out of joint by Richard at Sicily. Richard the Lionheart was only released in February 1194 after agreeing to pay the huge ransom of 150,000 marks.

Richard returned to England upon his release, but within a month was back in France. The final five years of his life saw him trying to re-establish his Angevin empire, which meant intermittent warfare with his one time ally Phillip II.

It was while besieging the castle of Chalus-Chabrol over a disputed trove of unearthed Roman gold that Richard was hit in the shoulder by a crossbow bolt. The wound became infected and after falling ill Richard the Lionheart died on the 6th April 1199.

He was buried according to his wishes at the feet of his father, Henry II, at Fontevraud and his heart buried at Rouen alongside his brother Henry. His brain and entrails were bequeathed to an abbey at Charroux on the border of Poitou and Limousin.

4. Lionheart's legacy

Richard the Lionheart was succeeded by his brother John who had schemed against him during his imprisonment.

King John’s reign was marked by the loss of much of the Angevin empire Richard fought to preserve. It also saw the revolt of the English barons which led to the signing of the Magna Carta, a charter of rights still seen as a seminal document in the forming of English constitutional practice.

King Richard spent hardly any time in England and like most kings of the period he would have spoken little English. Yet his military command on the continent and in the Third Crusade earned him admiration at home.

The size of the ransom raised and the speed in which it was done in order to free Richard may be a testament to how he was considered. The story of Blondel during his imprisonment also lends itself to the romance attached to the name Richard the Lionheart. Blondel was a minstrel who had composed a love song with Richard and he went around Europe singing this song in an attempt to locate his King.

Legend has it that Christendom was only made aware where Richard was being held when Blondel heard a part of the song sung back by the King through a window of his prison.

Later stories and legends helped cement Richard’s reputation as a popular king, including the tale of Robin Hood who was a supporter of the Lionheart after being outlawed during the misrule of Richard’s brother John.

A statue of Richard the Lionheart still stands outside the Palace of Westminster in London, while his seal is seen as the first instance where the three lions were used before becoming the Royal Arms of England.

Unfortunately visitors to Oxford will not be able to see the palace where he was born which has long gone, but a plaque in Beaumont Street commemorates where the palace once stood near the present site of Worcester College.