1. Darwin's life: a short history

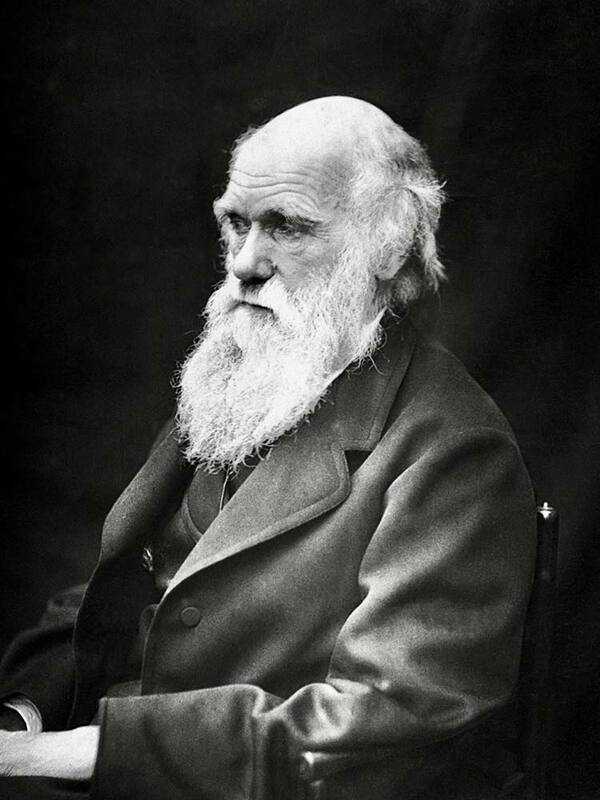

Charles Robert Darwin was born in 1809, the fifth of Robert and Susannah Darwin’s six children.

Darwin's childhood

Darwin was raised in comfortable circumstances, his father a doctor and financier.

But his childhood was not particularly happy: he was an average student (though he always enjoyed collecting things), much to the irritation of his father; he misbehaved (his diary records that he was, in many ways, a "naughty boy"); and his mother died when he was aged 12.

Darwin's main solace was the affection and doting of his sisters, Marianne, Caroline, Susan and Emily.

In his old age, Darwin still remembered a row with his father in which he was told that:

"You care for nothing except shooting, dogs, and rat-catching, and you will be a disgrace to yourself and all your family."

In October 1825, Darwin started a medical degree at Edinburgh University but developed a dislike for the subject when he observed an operation in which a child died.

The Priesthood?

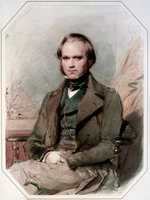

His father, believing that Charles was not living up to his potential, then sent him to read divinity at Christ's College, Cambridge with a view to becoming an Anglican priest. Though he did well in his exams, Darwin preferred botany, beetle collecting and the company of naturalists.

Interesting fact ...

Darwin was a zealous beetle collector. His diary records that, on one occasion, he had collected two rare beetles when he saw a third. He didn't want to lose it, so he popped it into his mouth. Unfortunately, it released a "intensely acrid fluid" and Darwin had to spit it out!

Darwin employed a labourer to collect beetles for him (by scraping moss from trees and collecting reeds from the bottom of barges). He was over the moon when Stephen's Illustrations of British Insects published a drawing of a new species of beetle that he had discovered.

Darwin enjoyed Cambridge in other ways: he spent time in the pub, was a member of the Glutton dining club, enjoyed shooting, and even stabled a horse nearby.

One key influence on Darwin came from the professor of mineralogy, John Stevens Henslow. Darwin often walked with Henslow on the Cambridge fens, learning collecting and classifying techniques. After he graduated, Henslow arranged for Darwin to go to north Wales on a geology fieldtrip and then pulled strings to get Darwin onto HMS Beagle.

The Beagle

Shortly after graduating in 1831, Darwin was invited to join the Voyage of the Beagle, an expedition to chart the coastline of South America.

In the event, the voyage also took in (amongst other places) the Galapagos Islands, New Zealand, Australia and South Africa, and laid the groundwork for Darwin’s idea that changed the world.

Darwin sent long letters to his family and to Henslow whilst on the voyage. He also sent back crate after crate of his collections, including the enormous head of an extinct giant sloth (called a megatherium). Henslow made sure that his protege's discoveries and letters were circulated to the scientific community.

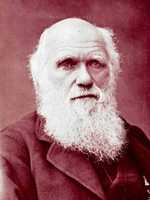

Darwin returned in 1836 a minor celebrity and went about cataloguing and writing up the diary of his voyage.

Eureka

Darwin's epiphany came in October 1838, after reading a book by Malthus on Population. He realised that, if all species face a struggle for existence, favourable variations will tend to be preserved and unfavourable ones destroyed.

But concern about the implications of his theory, further experimentation and ill-health meant that he did not publish the book for which he is best known, On the Origin of Species, for almost 20 years.

After publication, Darwin continued to work apace: he studied insect pollination, wild orchids, worms, climbing plants and the evolution of human psychology.

Personal life

Darwin died from heart failure at the age of 73 on 19 April 1882, survived by wife Emma and seven of his 10 children. He is buried in Westminster Abbey.

Interesting fact ...

Darwin was a scientist through and through. When he was deciding whether to marry Emma Wedgwood he drew up two lists: "marry" and "not marry". He concluded that "a constant companion and a friend in old age outweighed less money for books and the terrible loss of time."

His marriage was a happy one, though publication of On the Origin of Species may have been delayed in part because Darwin was concerned about his wife's reaction.

2. The Voyage of the Beagle

The Voyage of the Beagle was primarily designed to chart the South American coastline and not to advance naturalism.

Captain FitzRoy

But the Beagle’s captain, Robert FitzRoy, needed a gentleman companion and Darwin’s father was (after the intervention of Darwin's uncle) persuaded that his son should take to the seas.

FitzRoy was only 23 when he assumed command of The Beagle. His rapid rise was due to both family connections and natural ability.

FitzRoy initially became great friends with Darwin, but the two men grew apart as time went by: Darwin was liberal and starting to question religious orthodoxy; FitzRoy conservative and devout.

The voyage took in the Cape Verde Islands, the east and west coasts of South America (including Rio, Patagonia, the Falklands Islands, Patagonia, Chile and Peru), the Galapagos Islands, Tahiti, New Zealand, Australia and Cape Town. FitzRoy then insisted on sailing back to Brazil, so that he could check some measurements, before finally returning to England.

HMS Beagle

The Beagle was a Royal Navy 10-gun brig, 30 metres long and nine metres wide. It was unstable and an unsuccessful warship, known as part of the 'coffin class' on account of the shape of its hull and its propensity to sink, and had been modified when being re-assigned as a survey ship.

Interesting fact ...

Darwin was prone to seasickness, something he only discovered after boarding HMS Beagle. As a result, he used any excuse he could think of to spend time on land. Darwin spent about 60% of the 5-year voyage on land. After his return, he never left England again.

There were about 70 crew. Conditions were cramped, with Darwin sharing a small cabin with two junior officers. It doubled as a map room and was also stuffed with Darwin's specimens!

The Voyage

The voyage lasted almost five years, between 27 December 1831 and October 1836, and saw Darwin spending extended periods on land collecting specimens to be sent back to Cambridge for expert analysis.

This was a naturalist’s dream: Darwin discovered vibrantly coloured birds, saw sharks with T-shaped heads, earthquakes and volcanoes, and observed giant tortoises.

Interesting fact ...

Darwin was quick to appreciate the importance of studying tiny differences between members of the same species. He said that the maxim 'de minimis non curat lex' (the law does not concern itself with trifles) does not apply to biology.

It was during this period that Darwin grappled with the implications of two important pieces of information.

- First, the discovery of fossils which suggested that animals had lived on the earth for millions of years. Here, Darwin’s observations (on one occasion he found a fossil of a ten-foot sloth) confirmed and built upon the ideas found in Charles Lyell’s book The Principles of Geology. And they begged the question: could God really have created flora and fauna in the manner described in the Old Testament

- Secondly, that animals found on the Galapagos Islands were related but different in small but important respects (Darwin noted the differences between tortoises and mockingbirds in particular, though he also collected varieties of finch). This begged two crucial questions: how and why did they develop their distinguishing characteristics?

The Galapagos

The Galapagos Islands, meaning Turtle Islands in Spanish, were visited by Darwin and The Beagle in 1835. Found 600 miles to the west of Ecuador in the Pacific Ocean, the Galapagos comprises 14 islands altogether (the largest of which is Isabella). The Islands are all volcanic, with the youngest islands sporting active volcanoes.

Darwin was lucky to come across the Galapagos: it is the perfect laboratory for evolution. First, the volcanic landscape is harsh and inhospitable, meaning that only the fittest (or most well adapted) survive. Secondly, it has no large predators that can decimate the rest of the population, meaning that animals that could adapt to the conditions would survive. Thirdly, the conditions on the islands vary considerably, meaning that the same species evolved in different ways.

Diary

Darwin kept a diary whilst on the voyage. It was published, in the Colonial and Home Library by John Murray, in the early 1840s and proved very popular.

3. On the Origin of Species

Darwin published On the Origin of Species on 22 November 1859.

Central thesis

Its opening and final pages refer to Darwin’s dual contentions that “any selected variety will tend to propagate its new and modified form” and that only the animals or plants best suited to their environment will survive (survival of the fittest).

The result, as the last line of the book stated, was that

“endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

Interestingly, this is the only time the word 'evolved' is used.

Gestation

Darwin's theory was conceived in the early 1840s. In the course of 1842, he produced a 35-page "pencil sketch". And in 1844 he produced a considerably longer "essay". But Darwin held off publishing for a further 15 years.

Why? There were a number of reasons:

-

Darwin enjoyed being an active member of various scientific societies in London, in particular the Linnean Society. He knew his book was going to be controversial and was reluctant to risk bringing an abrupt halt to his happy working life

-

Darwin wanted more proof for his theory. He decided to spend a number of years studying barnacles, publishing well-received monographs for which he was awarded the royal medal by the Royal Society of London in 1853. He also corresponded with naturalists around the world, asking them to investigate particular issues and using the results of their research.

-

Personal issues slowed the pace of Darwin's work. He suffered from chronic bowel problems after returning from the Voyage of the Beagle. And Darwin's favourite daughter, Annie, died in 1851. It took Darwin a number of years to get over this bereavement.

Darwin's correspondence with other naturalists is voluminous: the Darwin Correspondence Project holds over 8,000 letters (Darwin destroyed many more). Post was the Victorian equivalent of the internet, with Darwin receiving five deliveries a day when living at Down House in Kent (properties in London received up to 12 daily postal deliveries!).

Publication

Publication was somewhat rushed following Darwin’s receipt in June 1858 of a paper written by Alfred Russel Wallace (a young specimen collector), which contained significant independently reached parallels with Darwin’s thoughts.

Darwin did not, however, seek to downplay Wallace’s work: the papers of both men were read to the Linnean Society at a meeting held on 1 July 1858.

Darwin's publisher, John Murray, could not have had high hopes for the book because the initial print run was limited to 1250 copies. They sold out on the day of publication, 22 November 1859, and a second edition was released the following January.

Darwin spent the next decade revising the book to meet arguments made against his theory, expanding its size by about 25%. It has since been translated into 29 different languages, including Icelandic, Arabic and Armenian. The Natural History Museum in London houses a collection of 500 versions of the book.

Publication of On the Origin had two further effects: it made Darwin world famous; and the royalties from the book made him a multi-millionaire in today's money (Darwin got 10% of the 15 shilling sale price).

Reaction

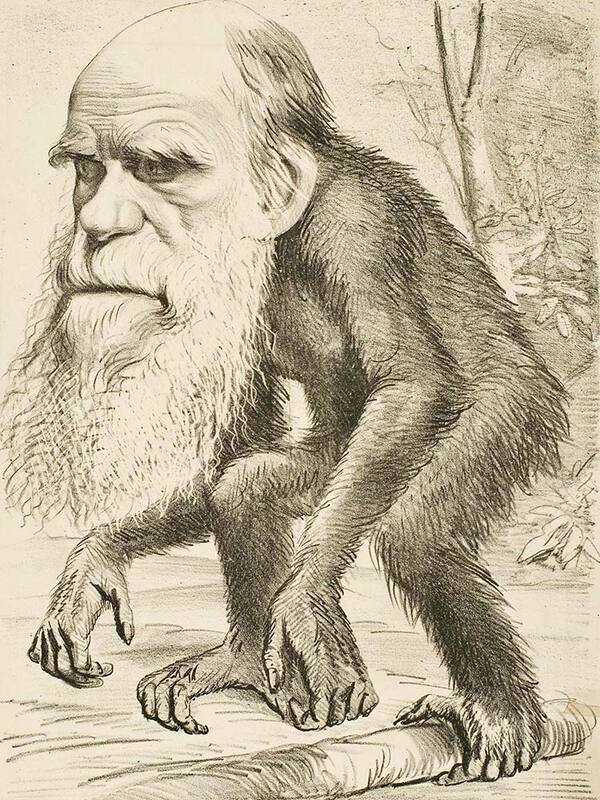

Reaction to publication was mixed. By and large the scientific community backed Darwin. Chief amongst them was Thomas Huxley, who published a book in 1863 showing that humans and apes share the same anatomy.

But many in the church, such as Bishop of Oxford Samuel Wilberforce (known as Soapy Sam on account of his skill at public speaking), did not.

Huxley, who became known as Darwin's Bulldog, and Wilberforce had a number of heated debates. They became known as the Oxford Evolution Debates.

When Wilberforce asked Huxley whether it was his grandfather or grandmother who was descended from an ape, Huxley said that he would rather be descended from an ape than be a person

"possessing great means and influence, and yet who employs those faculties for the mere purpose of introducing ridicule into a grave scientific discussion."

Darwin's theory was seen as challenging the credibility and supremacy of religion, and the following decades saw Darwin decried and accused of blasphemy, his face appearing on countless caricatures of apes. Darwin himself described the announcement of his theory as akin to confessing to a murder.

4. Later years, legacy and resources

Darwin devoted his later years to supporting the central thesis of Origin of Species, which is almost universally accepted today.

Incomplete?

Darwin himself was somewhat critical of Origin of Species, writing in the introduction that it was necessary to publish

"in detail all the facts upon which my conclusions have been founded."

He fulfilled this pledge, spending the last 22 years of his life providing those facts with a series of books about flowers, worms and humanity itself.

The Descent of Man

Origin of Species did not expressly address man: all that Darwin wrote was that his book might

"cast light upon man and his origins."

On the other hand, the intelligent reader would have appreciated that the argument in Darwin's 1859 book applied equally to man.

Darwin did not slow his frenetic pace of work, conducting countless experiments and writing extensively for the next 20 years. His 1871 book, The Descent of Man, proved even more controversial: it expressly suggested that humans had descended from apes.

There was another controversial aspect to The Descent of Man: Darwin argued that all races were descended from the same stock. This might seem inconsequential in modern times, but the proposition that slave-owning westerners were descended from the same line as their slaves shocked the educated classes.

Other works

Darwin published a number of other works in the last two decades of his life. They included an autobiography, written in two months in the summer of 1876 but not published until five years after Darwin's death, and a book on worms, published in 1881 (the full title of which is the not-so-catchy "Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms, with Observations on their Habits"!).

Darwin's death

Darwin had fits and seizures during his last years. He died on 19 April 1882, having had terrible convulsions the previous night, surrounded by his family. One of his daughters made a contemporaneous account of his last hours, so that she would have a record that he did not recant of his views.

Interesting fact ...

Darwin wanted to be buried in the Parish churchyard. But in London political forces were at work. His scientific supporters wanted his body to be placed into the public domain. The corpse was appropriated (some would say snatched) and taken to Westminster Abbey where it was buried alongside the monument to Isaac Newton at the north end of the choir screen. The nation's politicians and many foreign dignatories attended his funeral.

Legacy

Charles Darwin's theory challenged the biblical account of the world's creation, and perhaps religion more generally, postulating that man evolved over millions of years. It became the accepted orthodoxy within a remarkably short period of time and can fairly be said to be the unifying theory of all life sciences, explaining why life on earth is so diverse and complex.

It is no exaggeration to say that Darwin conceived the big idea of our age. We rank him the third greatest Briton, and the second greatest British scientist (a short head behind Isaac Newton).

Darwin was not the only Victorian who fundamentally changed how people saw the world. Isambard Kingdom Brunel, for example, provided a different contribution: by developing the Great Western Railway, bridges and steamships, he made the world a smaller place.

Resources

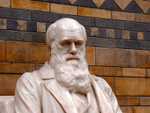

Darwin is commemorated in London's Natural History Museum, where a large statue of a relaxed and thoughtful Darwin presides over the main hall. Visitors can also visit Darwin's family home, Down House, where Darwin wrote Origin of Species and brought up his family.

Those wanting to learn more about Darwin might listen to Melvyn Bragg's four-part In Our Time podcast. And the Voyage of the Beagle is the subject for Harry Thompson's best-selling and Booker Prize long-list nominated This Thing of Darkness.