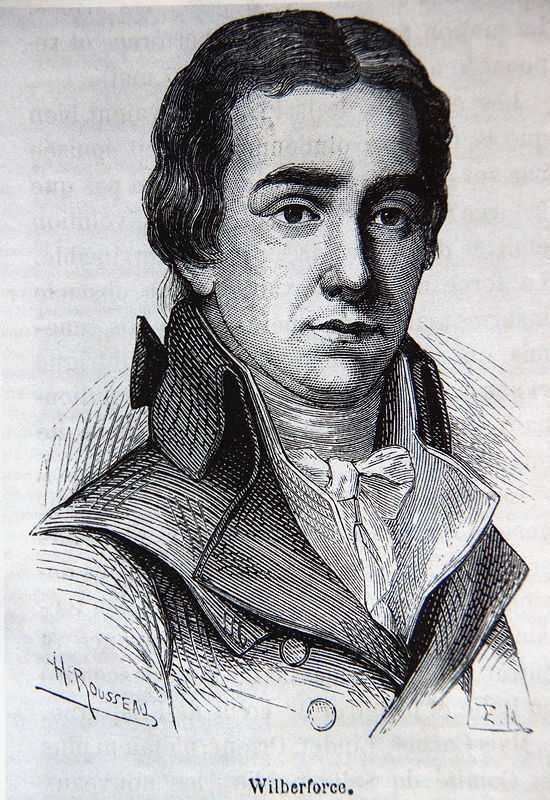

1. Wilberforce's early life

William “Billy” Wilberforce was born on August 24, 1759 in the port city of Hull. He was the third of four children and the only son born to Robert, a wealthy merchant, and Elizabeth Bird.

In 1767 Wilberforce began his schooling at Hull Grammar School. His grandfather, also named William, was an Alderman. He used his influence to secure the installation of Joseph Milner as the school’s new headmaster.

Milner had won the Chancellor’s Medal while at Cambridge University. His seventeen-year-old brother, Isaac, served as a temporary assistant.

Wilberforce’s father died when he was nine. His mother became seriously ill and the prognosis was not good. Wilberforce was sent to live with his wealthy uncle William and aunt Hannah at Wimbledon. They placed him in a school in the town of Putney.

Unlike his mother and grandfather, his aunt and uncle were devoted Methodists and dedicated to their evangelical Christian faith.

Wilberforce’s mother and grandfather never took their religious expression beyond church attendance and looked down on anyone who did otherwise.

When they discovered what Wilberforce was being exposed to, his mother whisked him back to Hull. He was sent to a school in Pocklington. Quickly, Wilberforce “backslid” into worldliness.

2. Early career

In October 1776, Wilberforce entered Cambridge. His uncle and grandfather died the following year in 1777 which left him independently wealthy.

Financially secure, he continued a lifestyle of parties and entertainment. While at Cambridge, he met William Pitt, son of Pitt the Elder, one of the most famous politicians and statesman of that day.

During their college years, they would travel to London to watch Parliament debate many subjects. Key among them was the fate of the American colonies who were engaged in a Revolution.

On October 31, 1780, at age twenty-one, Wilberforce was elected to Parliament. His friend Pitt also earned a seat a few months later. They soon rose swiftly through the political ranks to become two of the most powerful members of Parliament of that day.

They vacationed together and because of their status, they mingled with kings, queens, and diplomats. Wilberforce was known for his singing voice and became known as the “Nightingale of Commons.”

In 1784 Wilberforce was elected to one of England’s most prestigious seats, the county of Yorkshire. His friend, William Pitt, was elected prime minister of the nation. Pitt’s youth was atypical for such an important position. One newspaper derisively opined, “A sight to make surrounding nations stare. A kingdom entrusted to a schoolboy’s care.” Wilberforce and Pitt were a formidable duo and proved to be up to the task entrusted to them.

3. His finest works

In 1784 William took a long vacation to the French and Italian Rivieras with his mother and other members of his extended family.

The trip was around 1200 miles long. Two carriages were used. Wilberforce’s mother and the family members rode in one and Wilberforce and a guest rode in the other. Wilberforce paid for the travel expenses and he was careful about who shared his carriage for such a long ride.

Wilberforce’s close friend, Dr. William Burgh of York, was asked, but he couldn’t go. Later, at the Scarborough races, he ran into Isaac Milner, an old acquaintance from his days at Hull Grammar School.

On an impulse, he extended the offer to him. Isaac had achieved academic distinction. He was a Lucasian Professor at Cambridge and a very religious man. When Wilberforce discovered that, he was surprised and regretted that he had chosen Milner for a traveling companion. Milner turned out to be an affable traveling companion. He was cheerful and good natured, but he was an unapologetic Methodists.

While in Nice, Wilberforce picked up a copy of Philip Doddridge’s classic work The Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul. Doddridge was a Dissenting minister and hymnist of the early eighteenth century who had an informed and intellectual approach to genuine personal faith. Milner suggested that they read it on their return trip. By the time Wilberforce had reached London, his mind was racing.

Subsequent discussions with Milner about Doddridge’s book helped propel Wilberforce to embrace evangelical Anglicanism. He reread the scriptures that Doddridge had cited which resulted in him giving up everything that he felt didn’t please God, including parties and gentlemen’s social clubs. The next question was whether to stay in politics. With his newfound spiritual leanings, he felt he couldn’t be effective in Parliament.

Wilberforce remembered the religious period of his youth when he’d met John Newton. He turned to him for guidance. He hadn’t seen John Newton in over a decade. Newton had been a slave trade captain who converted to the Christian faith. He was the foremost evangelical in London at the time. Wilberforce fully expected Newton to tell him to leave politics, but, to his surprise, Newton told him to stay in politics because God could use him.

When Wilberforce left Newton, a weight had been lifted off his shoulders. He wasn’t sure about his next move, but the scriptures were clear. His wealth, talents, and his time were not his. It belonged to God and had been given to him to use for God’s purposes and according to God’s will.

Wilberforce prayed and read scripture every day. He even memorized scripture. In twenty minutes, he could recite all 176 verses in Psalm 119, which focused on the truth of God’s word.

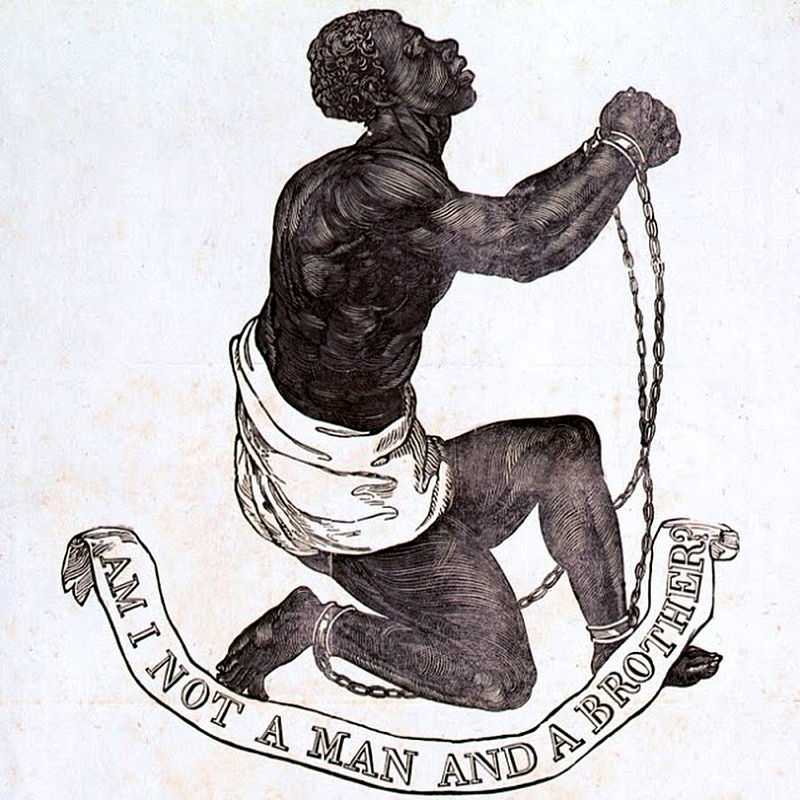

After almost two years contemplating what he should do, Wilberforce decided that God had assigned him two objectives; the suppression of the slave trade and the reformation of manners. He recalled how at age fourteen he had written to a Yorkshire newspaper criticizing the slave trade, however, tackling the slave trade issue would be a courageous move and risky.

Several abolitionists had approached him to champion their cause in Parliament. At first Wilberforce was noncommittal. He knew that courage flowed from wisdom, but, gradually, he came to believe that ending slavery was a moral cause and worth the risk.

The reformation of manners involved the morals and culture of Britain. A biblical worldview was foreign to the British culture. Wilberforce believed that this unbiblical view was central to why people used and abused others with impunity. Everywhere he looked, he saw misery and decay; the mistreatment of children, the excessive use of alcohol, and the use of teenage girls for sexual trafficking. He knew God had his back, but he would need the help of others.

Wilberforce befriended people who were theologically and politically on the same page as he. Most of these friends lived in Clapham, a village outside London, where he spent most of his time. They prayed and discussed every issue that confronted them. They became known as the Clapham Circle.

In 1797, eager to share his faith and to show the real difference between “real Christianity” and the phony “religious system” that prevailed, Wilberforce wrote a book, A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians, in the Higher and Middle Classes in This Country, Contrasted with Real Christianity. It was a best seller.

Still, after taking stock of his life, he realized that there was a void and he didn’t want to be alone. In that same year, he met, fell in love, and married Barbara Spooner. Within ten years they had six children. She was a devoted wife.

Her unconditional love was a godsend as Wilberforce would wait ten years before the Parliament passed the Abolition Act in 1807 that outlawed the British Atlantic slave trade. An additional twenty-six years would pass before the House of Commons passed the Emancipation Act in 1833 which outlawed slavery, three days before his death.

4. Wilberforce's legacy

William Wilberforce’s contributions to humanity are staggering. He proved that faith, social reform, and leadership could coincide.

For over fifty years, working with friends and enemies, he eradicated the British Atlantic slave trade and ultimately ended slavery itself.

Also, he changed the mindset of a nation into believing that those who are fortunate have some obligation to help those that are less fortunate.

The concept of “doing good” spearheaded many other changes and has remained in the western world ever since. Wilberforce didn’t just “talk the talk.” He “walked the walk.”

Wilberforce also brought about great change with style and rhetorical flourish. Here are some of his most famous quotes:

“If to be feelingly alive to the sufferings of my fellow-creatures is to be a fanatic, I am one of the most incurable fanatics ever permitted to be at large.”

“true Christians consider themselves not as satisfying some rigorous creditor, but as discharging a debt of gratitude”

“This perpetual hurry of business and company ruins me in soul if not in body. More solitude and earlier hours!”